Back to Homepage / Blogs / Jan 2018

An Eden of Islands - the Explorations of Dr Helfer

Felix Potter, author of the Myeik Heritage Walking Tour, is a historian currently researching for a book on the region. In this article Felix describes the dilemmas facing the British East India Company on acquiring the

Tenasserim region of Burma following the 1st Anglo Burmese War of 1824.

Even before British troops stormed into Tenasserim in 1824, the East India Company planned to give it away. They already understood what other conquerors had learned about the province : it is enticing to take, but expensive to

maintain and impossible to defend.

The financial drain of occupation made the matter urgent. Only two months after arrival, official correspondence confirmed that "The Governor General in Council adheres to his original opinion that supposing Tavoy and Mergui could be

both held by our troops for the present & without hazard or inconvenience, the best way of eventually disposing of them would be to give them over to the Siamese... "At one point, Brigadier General Campbell was instructed to simply

hand over Tenasserim to any willing recipient from Bangkok to Phuket", or "to any Siamese army which may be assembled on that part of the frontier."

Sentiments didn't change in the following years. Lord Bentinck, Governor-General of India, summed up the opinion in 1829, writing, "The expenditure far exceeded the income; no prospective benefit was held out as a counterbalance

against present loss." He also feared rebellions and inevitable collisions with new neighbours. The diversion of troops even threatened to weaken other parts of the growing empire, particularly India and Singapore.

The problem was finding someone to take it. Siam was reeling from decades of war with Burma and new conflicts in Laos and Cambodia. When the Company offered to exchange Tenasserim and the Mergui Archipelago for trade rights, Bangkok's divided palace was unable to respond. Long negotiations with the semi-independent state of Ligor (now Nakhon Si Thammarat) also went nowhere. The British even considered returning it to the Burmese, who refused to concede anything to the enemy for a province they considered rightfully theirs.

Less known but equally influential was the arrival of British commissioner A.D. Maingy. When he sailed into Mergui on 29 September 1825, he was appalled by what he found. The mainland and islands had been almost entirely depopulated,

with upwards of 90% of the population having fled, been enslaved by Siamese and Malay raiders, or killed in a desperate guerrilla war that had waged intermittently for 65 years. "It would be impossible to describe the distress and

misery occasioned by the depredations of the Siamese," he wrote. "Since our conquest not a village a few miles distant from the Stockade has escaped, and at least one-thousand and six-hundred Inhabitants have been carried away."

When Maingy saw Siamese prisoners in the Mergui jail, he ordered their chains struck off because they were ostensibly Company allies. Terrified residents immediately sent all women to hide in the forest while local men packed up

their belongings. The commissioner was disturbed, and the prisoners were again incarcerated until he could investigate the situation.

Very soon he concluded that for humanitarian reasons Tenasserim should not be ceded to either of the old combatants. He pleaded the case with emphatic reports to Lord Bentinck, and in turn to the colonial government in Bengal. To

walk away meant abandoning people to reprisals or abduction, Maingy said, and almost certainly a resumption of war.

Reluctantly, officials came to agree. Though its primary purpose remained the exploitation of conquered territories, the Honourable Company was no longer equivalent to the very dishonorable organization of previous centuries. Since

coming under supervision of the Crown and Board of Control in 1784, it had been forced to at least consider the welfare of its subjects in addition to profits. Its precarious political position was now tied to its reputation, which was

under constant attack by enemies in Parliament, rival merchants, and a British public that had always been skeptical of its overseas shenanigans.

Of course, that did not stop the directors from constantly grumbling about "our expensive and otherwise useless and mischievous occupation of the Tenasserim Coast." The British continued flirting with the idea of cession, but after

1831 it was not seriously pursued. Even a brief rebellion in Tavoy did not deter them. The territory simply had to be made to pay for itself, which they realized must be done through development of its natural resources. The Company

fetish for extensive taxation would never be sufficient given the poverty of the residents.

Years passed while nothing paid the bills for thousands of troops and improvements that Mr. Maingy and other commissioners requested. The promise of pearls never panned out, for example, because few free divers could descend the ten

fathoms necessary to gather wild oysters. Pearl farmers were brought from Madras, but costs exceeded profits and the project was abandoned. Expert divers from Malaya were hired in 1928, though only after the council in Penang approved

their demand to pay a "shark charmer" who could use spiritual powers to ward off fishy threats. The charmer apparently did his job—no injuries were reported—but this venture also proved unprofitable.

On the mainland the situation was worse. Historically, Mergui had never been self-sufficient in rice, and the problem was exacerbated by Siamese raids. Merguians were unwilling to risk their lives and liberty to work paddies far from

town. Mr. Maingy felt compelled to prohibit export of locally grown rice, because "had its exportation been allowed much distress would have prevailed at Mergui and among the poorer classes of this province." He also approved tax

forgiveness and land title reforms to encourage agriculture, but results were meagre and did not produce a surplus to feed occupying Indian troops who became sick from poor rations. No teak grew in the southern forests, and deposits of

tin and coal were difficult to access. Worst of all, a cattle epidemic in 1836 wiped out one-third of the livestock. Carefully made plans from Mr. Maingy to develop the province had to be abandoned in the aftermath. By then, the

commissioner had retired, his health broken by overwork.

HELFER IN THE FOREST

Thus, in 1838 the East India Company turned to a young man named Johann W. Helfer. As a naturalist, physician, scientist and explorer, he was hired to survey the vast province for products that might defray its enormous cost.

A native of Austrian Prague, Dr. Helfer was more than ably assisted by his wife, the brave and intelligent Baroness Pauline des Granges. They were relieved to get the job. Helfer had inspired her with dreams of adventure and the

quest for knowledge, but while travelling overland from Europe they had been swindled by con artists posing as Afghan princes. The young couple was happy to explore Tenasserim instead of returning home.

As had happened with each other, they immediately fell in love with the place. Assisted by porters to carry supplies and collections, the Helfers' first journey took them up the Salween River from Mawlamyine. All went smoothly. The

doctor was rapt with his collections, and the baroness was in awe of the ingenuity and resilience of the people they met.

The next expedition to the Three Pagodas Pass was far less fortunate. Lost for weeks and unable to find help in the depopulated forest, the entire group struggled to survive. Their food ran out and people grew sick with dysentery.

Starving, exhausted porters first set down their loads and then themselves when they could walk no further. With 51 people to feed, Karen guides managed to kill a few monkeys, birds, snakes and lizards to keep them barely alive. The

forest people gave their scant remaining rice to the Austrian baroness, telling her "There, take our rice. You white women can't live on roots and berries in the woods as we can." Their noble generosity overwhelmed her with emotion.

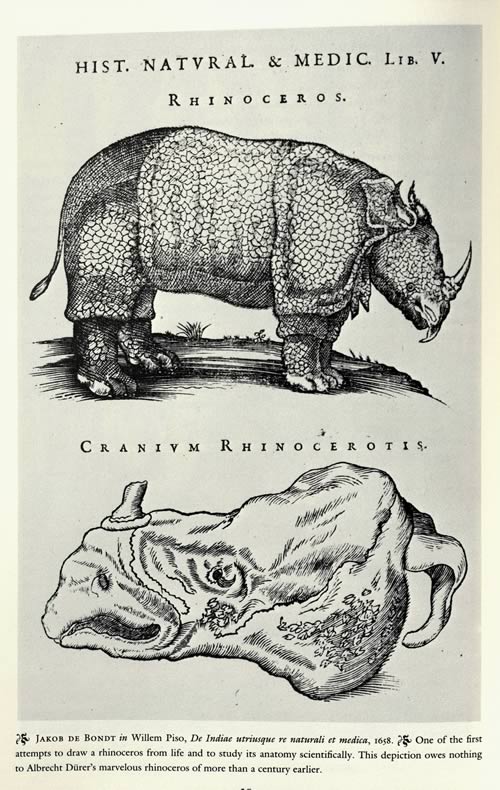

Finally, after being attacked by an enraged rhinoceros (which they killed and ate), the guides and Dr. Helfer managed to lead the caravan out of the jungle. Their grave fears for the invalids left behind were not realized, as one by one

they were retrieved from the trail. With everyone safe and bellies full at last, Madame remarked, "Never have I felt so keen a sense of the brotherhood of all men as at that time among these so-called savages."

More expeditions followed, though Madame Helfer remained in safety near Mergui town. She used a grant of free land to carve a plantation out of the jungle while the doctor explored the Tenasserim River. Again he noted the effects of

past conflict. "Excepting the site of the old town of Tenasserim and the new settlement of Metamio," he wrote, "there is properly speaking not one single village along its whole course." The forest, on the other hand, was full of

specimens to add to his collections, and products that might be developed for the Company.

HELFER IN THE ISLANDS

The naturalist was indefatigable. Young, fearless, and driven by intense curiosity, he next set out to explore the Mergui Archipelago. On 28 November 1837, Helfer departed from Mergui in several open boats and sailing canoes. His

companions were twenty-five local Merguians who knew the islands mostly from rumours and furtive fishing trips.

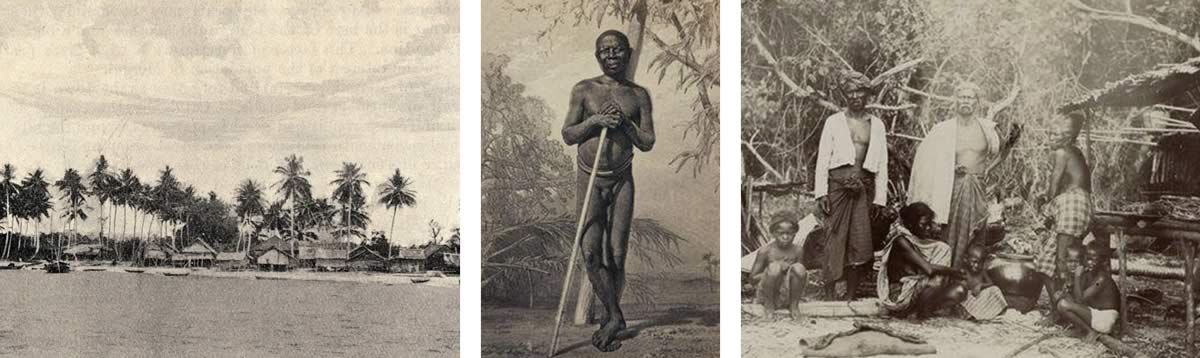

It seemed like a journey into Eden. Having been the haunt of pirates for sixty years, the archipelago was nearly pristine. Nature had reverted back to its virgin state in the absence of fishing, collecting and settlement. Only the

Moken still lived there. Madame Helfer wrote, "He found the islands mostly uninhabited, but came sometimes upon remains of former settlements or temporary abodes of Malay pirates, who, before the time of British dominion, made these

waters so dangerous. On the larger islands he observed scattered, deserted camping-places of the scanty nomad race, the Seelongs [Moken]. They are a peaceful people without settled abodes, who fly from hostile attacks into inaccessible

mountains, or try to escape them in light boats, in which they glide rapidly over the water."

Like all Edens, this one was tainted. The Moken still in the islands were ones who had survived attacks of far more dangerous foes than pirates. In a tragedy that afflicted indigenous people across the earth, foreign pathogens caused

epidemics well before most victims ever saw a foreigner. The 1820s were particularly deadly in the Mergui Archipelago, with mortality among some bands of Moken reaching 50% during initial waves of smallpox. Their elders, Helfer

reported, only considered a child to be safe from disease after the sixth birthday. The doctor himself was unaware how these epidemics operated, as it was decades before the germ theory of disease was fully understood.

In everyone's ignorance, Malay pirates remained the greater threat. Dr. Helfer described his first attempt to visit a band of Moken in the Blunt Islands, near Lampi : "My arrival at night terrified the defenceless natives, as they

did not know whether I might be friend or foe, and feared an attack of Malays from the south. The women and children had fled into the interior, having concealed their small possessions, rice and cockles, in the thickets. Everything was

in the greatest confusion; even the animals were scared at the unwonted visit, for dogs, cats, and cocks set up a shrill chorus."

With patience, however, he convinced them that he meant no harm. Gradually, the people returned to the beach to meet the first European they had ever seen. Helfer was impressed, writing, "They behaved with remarkable civility and

decorum." One wonders if the nomads said the same about him, as the Moken's previous experience with outsiders had been so traumatic. Helfer added, "By all who have to do with them, (Chinese and Malays) they are provided with toddy in

the first instance and during the subsequent state of Stupor, robbed of any valuable they possess. They gain however so easily what they want, so that they do not seem to mind much the loss when they come again to their Senses."

The Moken were as interested in Helfer as he was in them : "When they saw me drink Coffee, and heard that I drank the black substance every day, they concluded this to be the great Medicine of the White man, and were not satisfied

until I gave them a good portion of it." Nearly two centuries later, we know their demands were entirely justified!

The little flotilla left the Moken to continue its explorations. While Helfer sought scientific knowledge, his companions hoped to find other riches. For thousands of years, the Malay peninsula had been fabled as a land of treasure.

Hindu legends called it Suvarnabhumi—the land of gold—and the dream would still influence masses of impoverished Indian labourers who ventured to British Burma during the rice boom of the early 20th century. Europeans were equally

infatuated. Ptolemy called it Aurea Regio in the 2nd century C.E., and European cartographers labelled it "the Golden Chersonese" until the 1800s.

Of course the exact location was never given. The gold was said to be located somewhere between Sumatra and Pegu, a region large enough to keep fortune-hunters busy for centuries. Helfer listened to the rumours with amusement :

"Since my first arrival at Mergui when it was known amongst the Natives that I came into the country to look at all kinds of Stones, Plants and Animals, I had at different times visits from Malays, Shans and Burmese, all of whom spoke

of an Island in the Archipelago, which contains gold in great abundance. Marvellous stories were added to it, of neels [shrimp] who guard the treasure, of storms which arise when anybody dares to take the gold away. It was my intention

this time to visit this island, touching at others the same time which I had not yet seen. Where however this Island was situated nobody knew in Mergui."

His companions assured him that the treasure was always "beyond the next island." The doctor didn't mind. He diverted their enthusiasm to help collect hundreds of specimens of fish, shellfish, birds, mammals, insects, trees, grasses,

and marine organisms. He took geological samples, observed the collection of edible birds nests, and contacted more bands of Moken. Eventually, the crew took him to a remote island where yellow metal glittered in a riverbed. Helfer was

not deceived; it was only fool's gold.

No one was discouraged. After a brief return to Mergui, Helfer and his crew continued their respective searches. On 27 February 1839, the Burmese guided him past the Bentinck Island group, which the doctor described as "weather-

beaten rocks full of indentures, steep sides, and narrowed valleys. Their western side is generally exposed to the violence of the Seas, their eastern side is surrounded by a smooth sea . . . the whole scenery altogether moved lake-

like."

Gold fever struck again : "The people had again to show me something particular occurring on one of the outer rocks of Observation Island, which is considered a talisman amongst the natives. I went in a small canoe to look at it, and

found the crystals from pyrites whose bronze yellow made them appear to be gold."

With the fever came the usual dangerous consequences : "The surf beating violently caused a great swell, our canoe was suddenly breached by a wave, shipped water, and filled instantly. We were about 30 yards from the shore and swam

for it. The surf took hold of me and dashed me with violence against the rocks, which were covered with [molluscs and sea snails], and I was all bruised and cut by the knife-like edges and sharp spines of the shells. I succeeded however

to climb up the rock before the next shock of the surf. Nobody perished, my Burmese people clung to the canoe, and others came over to our assistance. I was brought into my boat, out of which I could not move for the next three days. It

was necessary to extract the spines . . . and I had about 50 fragments sticking in different parts of my body."

After recovery during another brief visit to Mergui, Doctor Helfer visited King (Katan) Island Sound, "where the French fleet waited in the last wars against the British stationed on the eastern side of the Bay of Bengal, for the

purpose of intercepting the India Men trading to China." Older people in Mergui could still remember these naval vessels and privateers, who made strategic use of the sheltered bay during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1792 –

1815). Because the northeast monsoon closed down ports on the east coast of India from October to January each year, the French were able to dominate the Bay of Bengal months before the British navy could sail around from Bombay.

"Numerous are the stories of the Frenchmen which the elder Burmese inhabitants have to tell of them," Helfer wrote, including tales of a stockade next to "French Watering Creek" on King Island. Helfer found no trace of their presence

there, which of course did not deter his companions from renewing their search for treasure : "My people, like hundreds had certainly done before them, rummaged the whole place over, and would have continued so in the Evening had not

the shrill piercing voice of the Tigers in the vicinity driven them back to the Sea Shore."

Unlike the island of gold, Mergui's tigers were no fable. Excellent swimmers, they had populated the entire archipelago and could ambush people from anywhere. Local people did not possess adequate weapons to fend them off. Helfer

also noted that island tigers were more aggressive than mainland cats due to a scarcity of large game. "The Western side of King's Island," he wrote, "is said to be the most dangerous in that respect and several well thriving Durian

gardens had been abandoned on account of Tigers." At least the doctor had no further trouble with rhinos, which also inhabited the archipelago.

As his scientific collections continued, so did his exploration of legends. Helfer next took the boats to Kisseraing (Kanmaw) Island to investigate tales of a lost city : "This Island though now entirely desolate of all fixed

population is said to have been once very important, crowded with villages, the greatest part of the soil converted into fields yielding a superior quality of rice which was exported to the neighbouring Countries. Whether in truth or at

what time this was the case, and what was the reason of the total disappearance of the population we possess no means to indicate at the present day. That the island was inhabited is proved by the numerous remains of Pagodas to be met

within different parts of the Island." To this day its archaeological history remains unsurveyed.

More recently the island had been a notorious lair for Malay pirates who had so terrorized Merguians that people seldom ventured more than a few miles from town. After British occupation, a few fishermen were finally returning to

Kisseraing to catch "the immense number of fish which migrate into the inner channels to deposit their spurm there, in millions." This abundance also attracted large numbers of cetaceans, giving its eastern side the name, "Whale Bay."

Mercifully, the voracious Yankee whalers who were scouring the seas had yet to reach the Mergui Archipelago in 1839.

Too soon, signs of the southwest monsoon hastened the end of Helfer's island adventure. He turned his tiny armada northwards towards Mergui town. The doctor took a last opportunity to visit Maingy Island, named for the man who had

convinced the East India Company to protect the long-suffering residents of Tenasserim. Naturally, Merguians had established a small factory there to produce its most famous product : "[Maingy Island] is resorted to by fishermen from

Mergui to prepare ngapee, this indispensable condiment to a Burmese in his cooking ingredients. I found a party of ten men lodged in a miserable shed on this Island occupied with the preparation of this substance. The stench was

dreadful to European olfactory nerves so that I hastened away from this pestilential atmosphere as quick as the tide permitted . . ."

One can only imagine Helfer's terrible suffering as he waited for the tide to allow his escape. The doctor soon had his ironic revenge, however. He began collecting "zoophytes," small marine creatures that he wished to examine back

in town. Unfortunately, science turned rotten in the heat. "When taken out of their element," he wrote, "the animals after death putrify and cause an insufferable stench. The Burmese, though their olfactory nerves are in other respects

not at all delicate, declared that they could not bear it."

After two days, all his crew was sick and had festering carbuncles on their legs. The doctor chose sympathy for his companions over dedication to craft and Company. He cast the creatures overboard. He was not too disappointed,

though, because he had already collected vast amounts of specimens and data to process in Mergui. The plantation had also flourished under the care of the baroness, and the couple must have looked forward to their reunion.

Doctor Helfer's reports are fascinating for their images of the forests and archipelago in their natural state. But they are also interesting for the portraits of the young European couple themselves. The doctor was a product of his

education, which in the early 19th century was infused with racist theories of Caucasian superiority. He was hired by the notorious East India Company to help exploit its occupation of a foreign land. And yet, as he spent more and more

time among local people, his curiosity and humanism steadily began to displace the racist ideas he had been taught.

While in official reports he resorted to dismissing them as child-like, in his personal accounts he was filled with respect and sympathy. He both risked his life for his Asian companions and trusted them with his own.

Madame Helfer likewise came to admire the people of Tenasserim. Though she arrived with the conviction that they needed Christian civilization, she slowly found herself tempering that belief with deep respect for those around her.

While her husband was away in the islands, the baroness even felt empathy for the Thugs—convicted serial murderers transported from India—in whom she found humanity and decency deserving of forgiveness.

HELFER IN THE ANDAMANS

Doctor and Madame Helfer were two of a long list of remarkable people in the story of Tenasserim. That is why his next expedition was so tragic. After spending the rainy season developing the plantation with his wife, and after they

resolved to stay in Mergui forever, he set off to explore the Andaman Islands. The islanders were known across the Indian Ocean for their hostility to outsiders. Sailing directions and tales of shipwrecks spoke of ferocious attacks by

enraged men armed with spears and arrows. Helfer was cautious but undeterred. On January 29th, 1840, he bravely went ashore to make contact.

At first, the reputation of the Andaman Islanders seemed as fanciful as the land of gold. They were cheerful and provided wood and water in exchange for rice and coconuts. Helfer left in high spirits. The last words in his diary

were, "These, then, are the dreaded savages! They are timid children of Nature, happy when no harm is done to them. With a little patience it would be easy to make friends with them."

When he returned the next day, he was so confident that he ordered his crew to leave their weapons behind as a display of trust. Something went wrong. Different men met the party and lured them away from the beach. Suddenly, dozens

of Andaman Islanders emerged from the forest to attack. The visitors fled in panic to their canoes which overturned in the surf. They began swimming frantically back to the schooner while a rain of arrows issued from the angry men on

shore. The wounded men reached the schooner, but not the young doctor from Prague. He took an arrow in the head and sank beneath the sea, never to be seen again.

Madame Helfer was distraught. She attempted to continue in Mergui but the spell was broken. The widow soon returned to Europe, where she remarried and became Countess Pauline Nostitz. Even then Tenasserim held a fascination for her,

as she dreamed of establishing a German colony on the far side of the world. Her brother, Baron des Granges, continued to manage thousands of areca and coconut trees on their land and even braved the tigers to set up a new plantation on

King Island. After six years his health was destroyed, the orchards fell into disrepair, and authorities in Bengal conveniently forgot about the promises they had made to the late Doctor Helfer. Interest from the King of Prussia could

not rescue the project either. The Countess was forced to seek compensation from East India Company directors in London, while her plantations were once again relinquished to tigers, rhinos, and the patient Tenasserim jungle.

Myeik Heritage Walking Tour book and website

A historical guide to the fascinating town of Myeik in southern Myanmar. The guide includes a walking tour route map, color photos, and descriptions of 46 places of interest. Also included are discussions of Myanmar history in general, the Mergui Archipelago, and the British colonial era in which so many of Myeiks' buildings were constructed. The guide was created from archival research and the help of local residents.

CLICK HERE to buy this book on Amazon

CLICK HERE to visit the Myeik Walking Tour website

Sources

Though some of this article draws upon archival sources, one can freely download Madame Helfer's Travels of Doctor and Madame Helfer in Syria, Mesopotamia, Burmah, and Other Lands :

Volume one, from

Prague to Iraq: https://archive.org/details/travelsofdoctorm01nost

Volume two, from Iran to the Andamans: https://archive.org/details/travelsofdoctorm02nost

Many of Dr. Helfer's diaries and collections were lost at sea, but thousands of specimens are still held by the National Museum in Prague.