Back to Homepage / Blogs / Nov 2018

Burma: when the fairy tale is over

Filmmaker and historian Alex Bescoby makes the case for why even in these dark days it's more important than ever to consider a visit to Burma.

Ethnic cleansing. Jailed reporters. International sanctions. Travel boycotts.

It was headlines like these that haunted my steps as I first crossed into Burma (now Myanmar) in July 2008.

For much of the last ten years I've called this country home, and been witness to one of the most remarkable periods of political and societal change in this country's modern history.

Finally, Burma was emerging from decades in the darkness.

I watched the joy on family's faces as their relatives were freed after years wrongly held behind bars.

I joined the hustle at the news-stand as censorship was lifted, and the bustle of new business as international sanctions were torn down.

I danced in the streets on November 8th, 2015, wide-eyed in wonder at the country's first credible election in more than 50 years.

And I saw those same streets fill with curious tourists, itching to roam a country so long closed off from the Western world.

But over the last 12 months the tide of good news has turned on its head. Burma's fairy tale march towards a peaceful, democratic, multi-ethnic utopia at first stumbled, then fell flat on its face.

Week after week, news bulletins filled with the desperate sight of hundreds of thousands of Rohingya Muslims fleeing an orchestrated campaign of indiscriminate killing, rape and destruction by the Burmese military.

Meanwhile, Burma's democracy icon – Daw Aung San Suu Kyi – shocked the world with her refusal to condemn the crimes of the military, or the jailing of Burmese journalists who sought to reveal them. The world swiftly turned on 'The Lady' who could once do no wrong.

Calls for drastic action ring out around the world, the same grim headlines fill the air, and tourist boycotts are back on the agenda. It feels like the last ten years never happened.

What happened to the fairy tale we were promised?

Well, like most fairy tales, it turned out to be nonsense. Take that as your starting point, and the events of the last 12 months start to make a little more sense.

Ethnic conflict, oppressive government, political crisis – they are in fact the norm, not the exception in the story of modern Burma. What we see today is just the latest spike in a series of deeply rooted and interconnected problems afflicting this country.

It was something I quickly began to learn when I arrived in Burma ten years ago to study its history. Part way through I swapped pen and paper for a camera crew, and began to explore through documentary film a story in which my own country, Britain, has played a leading and often rather

villainous role.

I spent three years filming with Burma's lost royal family, learning how in 1885 Britain toppled Burma's millennium old monarchy and turned this fiercely independent kingdom into a mere colony within British India. I listened how during the decades of colonial rule, Burma's politics, economy

and society were radically disrupted, while the memory of monarchy refused to fade away.

I spent a further two years tracking down veterans of World War II in Burma. Heading into the country's most remote corners to meet men who had risked their lives fighting for Britain against the Japanese, I discovered how what had been a decisive victory for Britain and her allies had

simply been the start of a series of intractable civil wars between Burma's many ethnic groups.

I learnt how at independence in 1948, Burma's economy was in ruins, its institutions fragile, and its population heavily armed and bitterly divided. It's clear from events today that 70 years on, the country has not yet moved beyond this legacy of poverty, war and political crisis.

"What went wrong?" is in fact the wrong question. With history as our guide, the better question should be: "Did we expect too much?"

Now the fairy tale is over, there are two burning questions that face today's potential tourist – is it safe to go, and is it right?

The answer to the first question, from my own experience, is a resounding yes. In 10 years of travelling to every corner of this incredible country, I have never faced so much as a rude remark.

Where foreigners can travel to is still quite strictly controlled, and as the number of new arrivals plummets, local and national authorities have an even keener interest to keep tourists safe and well.

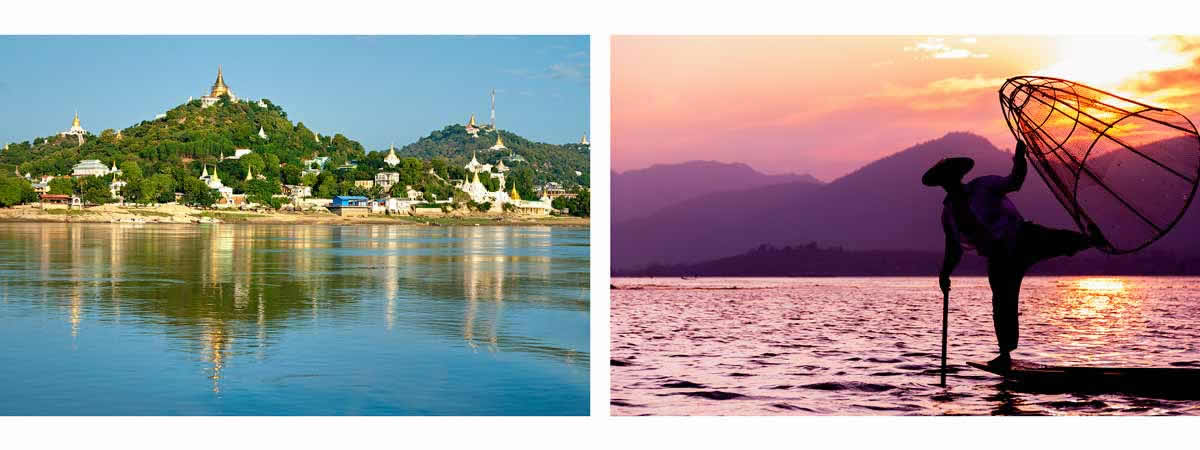

Anywhere remotely contentious due to ongoing conflict remains off limits, and the country's most famous sights – the ancient temples of Bagan, the old royal city of Mandalay, the floating gardens of Inle Lake, remain perfectly safe and accessible as ever.

The second question is more difficult to answer. Is it right to travel to Myanmar? My answer is, for now, yes.

The grim reality is that a travel boycott by Western tourist will do little to punish those responsible for the treatment of the Rohingya. More importantly, it will do precisely nothing to help the Rohingya themselves.

What it will certainly do is damage a home-grown industry of family-owned guest houses, shops and restaurants across the country who have invested everything they had into Burma's tourist boom. They had nothing to do with the events in Rakhine state, and now face losing it all as tourist

numbers slump.

On my many journeys across the country this year, I can already see reality biting - the child kept back from school, the urgent medical treatment delayed, the debt-collectors descending.

But I fear the most valuable thing Burma stands to lose from tourists turning away is the most tangible change I have seen in my ten years living and working here. It's a growing confidence among its people to speak to, and a burning hunger to learn from, the outside world.

Over the last decade I've watched Burma shake off the dust of isolation and embrace an explosion of art, literature, thought and music fired by a period of unprecedented intercultural exchange with visitors from abroad.

It was a hard-won chance that for decades the people of Burma were denied, and it's one that risks disappearing just as quickly as it arrived.

The people of this country are expressing themselves in ways that will continue to surprise you. As an informed, responsible and curious tourist, you can be the audience that now, more than ever, they so badly need.

Whether it's the former political prisoners exploring the trauma of dictatorship and war through modern art at The Secretariat Building in Yangon, or its rappers and punk rockers preaching religious tolerance in the backstreets of Mandalay, or its brave journalists battling for press freedom in one of the countries English-language weeklies – the people of Burma are refusing to go quiet.

And I believe we owe it to the long-suffering people of this beautiful, benighted country to keep listening.

In these darker days, you might not like what you hear, and it certainly won't be the fairy tale we were all hoping for, but I can guarantee it's still a story worth hearing.

We Were Kings dates are:

OXFORD

Date: 23rd November 2018

Time: 1700-1900 (inc. filmmaker Q&A)

Venue: The Old Library, Lady Margaret Hall, University of Oxford

Tickets: £12 (£8 student) + free drink

Click Here to purchase tickets

DUNDEE

Date: 13th December 2018

Time: 1830-2030 (inc. filmmaker Q&A)

Venue: Dundee Contemporary Arts Cinema, 152 Nethergate, Dundee, DD1 4DY

Tickets: £10 / £7 / £6.50

Click Here to purchase tickets

Alex Bescoby is an award-winning documentary filmmaker, writer and presenter with a love of history, travel and storytelling. Alex co-founded independent production company Grammar Productions to make innovative documentaries that delve deeper into history and how it affects he lives of people and societies around the world today. Since studying politics and history at Cambridge University, his work has taken

him to some of the less-travelled corners of the world, including the back-country of Sierra Leone, the remote Peruvian Andes and the insurgent-ridden southern Philippines. His most recent projects have involved filming over several years in far-flung corners of Myanmar (Burma). You can learn

more about those here.