Back to Homepage / Blogs / Oct 2017

The Old King's Ghost

I've come to the British library, joined by an old friend from Myanmar (Burma) on his first visit to London.

It's an odd place to start a tour of London, but we're here to see an item from the Library's collection that's never been displayed before, and that my friend has asked to see.

We carefully open the protective box to reveal a dark red rectangle, about the size of a large takeaway menu – a parabaik. These concertina books, made from mulberry paper, are distinctive to pre-colonial Burma. Across its twelve folded pages this parabaik tells a story that's bewitched me for over a decade.

Inside, sketched in delicate watercolour and edged with gold, is a series of events that took place over a century ago, but the echoes of which are still being heard today.

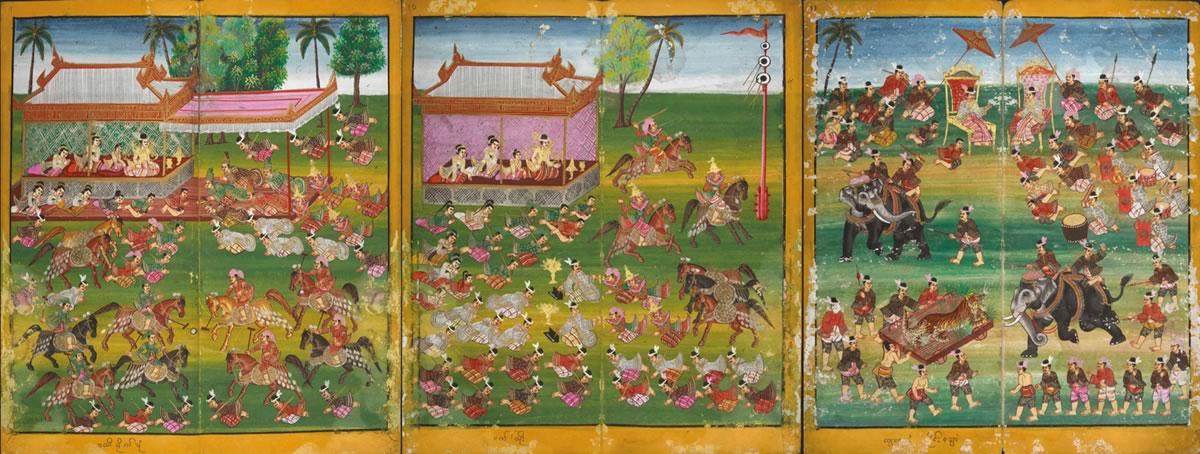

The 'Deposition Parabaik' (Or. 14963) – credit British Library

The 'Deposition Parabaik' (Or. 14963) – credit British Library

The toppling of Burma's last King, Thibaw, by the British government in November 1885 had the most profound impact on Burma - a millennium old monarchy was ended, a fiercely independent kingdom became a colony within British India, and the tapestry of Burma's politics, economy and society would be radically altered.

Ironically, for such a seminal event in the shared history of Britain and Burma, which had deeply profound consequences for the latter, almost no one in Britain even knows about it.

Stretched out across the reading room table, my friend and I begin to trace a story we both know far too well. At the far end, we catch our first glimpse of King Thibaw perched on a golden throne.

An issue with the issue

King Thibaw (R) and his two queens - Suphayalat (M), and Suphayagale (L)

King Thibaw (R) and his two queens - Suphayalat (M), and Suphayagale (L)

Thibaw was an unlikely choice to succeed his father, King Mindon, who had ruled the kingdom skilfully for a quarter-century. Mindon, in the fine tradition of Burmese kings, had taken more than 40 wives and is thought to have fathered more than 100 children.

With so many sons to choose from, and the law of primogeniture not being a strict convention, on Mindon's death in 1878 the question of succession was a tricky one. Thibaw - a quiet, scholarly boy of 19 whose mother was a minor queen – was manoeuvred onto the throne past numerous stronger contenders. He was seen by powerful figures at court as a pliant puppet, a king who could be the face for badly needed reform.

With so many potential sibling rivals, however, Thibaw's position was precarious. In 1879, the first year of his reign, the powerful forces behind him (including his own mother in law) set out to make it less so. They orchestrated an infamous massacre, in which all the royals close in age to Thibaw were rounded up and killed – scores of princes and princesses were bludgeoned to death, the corpses allegedly wrapped in velvet and trampled by elephants.

Splendid isolation

For now, Thibaw was secure on his throne. In the parabaik, he's depicted alongside his two Queens (both half-sisters by blood) and eldest daughter watching sporting and devotional ceremonies in the ornate walled palace of Mandalay. Elephants and tigers square up, and Burmese polo players are frozen mid-gallop, as Thibaw looks on shaded beneath delicate umbrellas.

Outside this scene of peaceful pomp, however, powerful forces were brewing. In two wars with the British government, Thibaw's predecessors had ceded half of the kingdom, including the entire coastline and the country's most fertile rice-growing regions. Beyond the walls of his gilded world what's left of Thibaw's kingdom is crumbling, and the great European powers are circling. Thibaw stands in the way of a lucrative trade route to China, and sits on top of bountiful supplies of teak, oil and gems.

Downfall

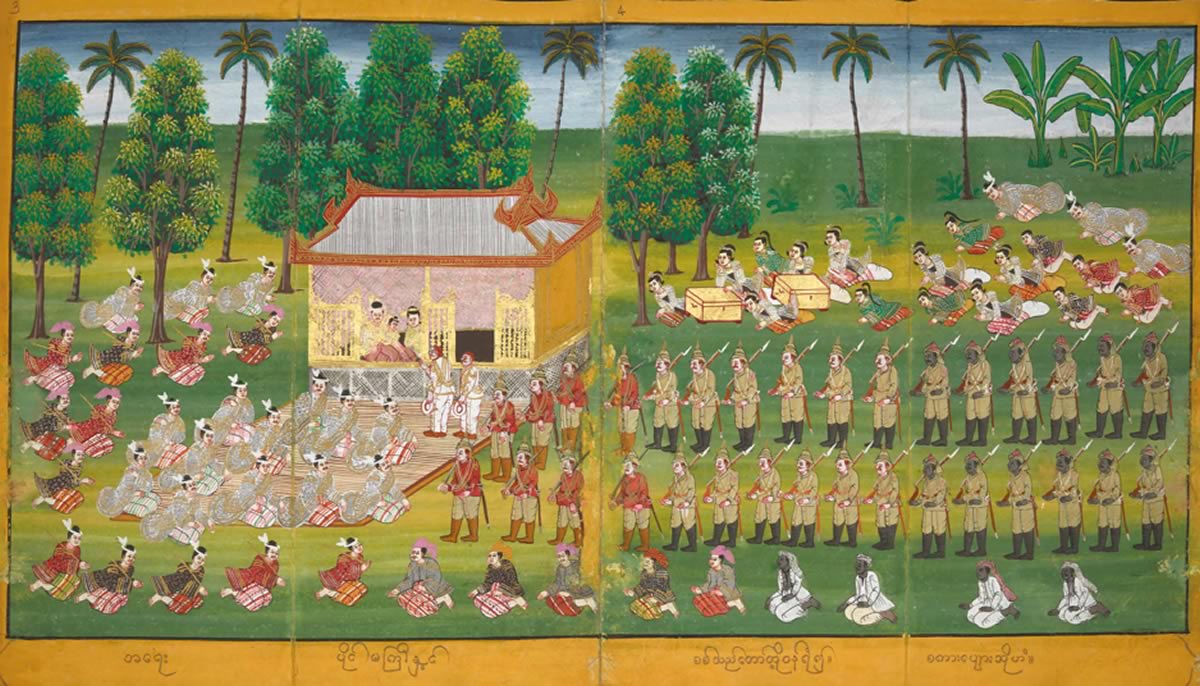

In the middle of the parabaik, palace life is abruptly interrupted by the arrival of the 'Burma Field Force' in red and khaki, on the 28th November 1885. This specially assembled invasion force consisting of British and Indian brigades was under orders from the Secretary of State for India, Lord Randolph Churchill – father of Sir Winston.

The 'Deposition Parabaik' (Or. 14963) – credit British Library

The 'Deposition Parabaik' (Or. 14963) – credit British Library

The British government had lost patience with Thibaw, and were concerned he was close to falling under the influence of the old enemy, France. His time was up – "this will be the third and last struggle I hope with Burmese arrogance", wrote Colonel Edward Sladen, the expedition's Chief Political Officer, in early November 1885 as he prepared to sail up the Irrawaddy river with the troops. The war lasted a matter of weeks, and the King quickly surrendered his kingdom in the face of overwhelming force.

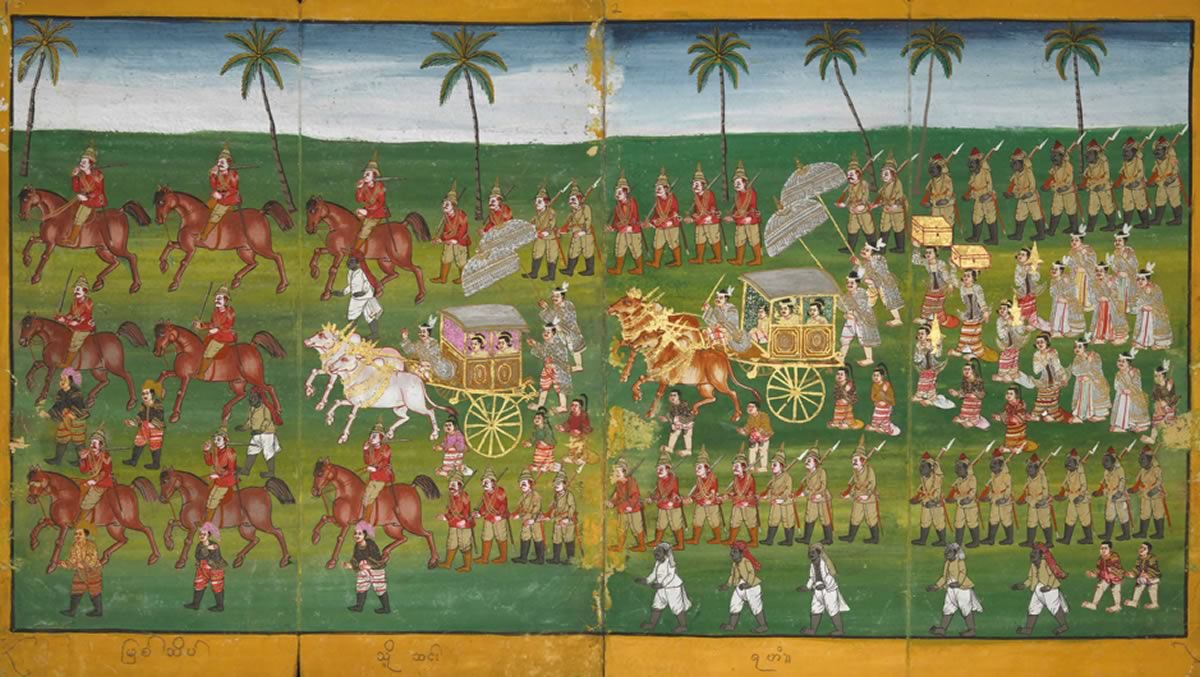

The parabaik shows the King and his family being escorted first to the South Gardens of the palace, then on November 29th carried by bullock-cart to a steamer. It would take them into what for the King would be permanent exile in India. He would die in 1916, diminished and heartbroken, in a small fishing-village on the country's west coast. His body is still entombed there today.

We Were Kings

Thibaw's great-grandson, U Soe Win - de-facto heir to Burma's throne - is sat right next to me, studying the last moments of his famous great-grandfather closely.

Ours is an improbable friendship, separated by thousands of miles and several decades. Three years earlier, fascinated by the events of November 1885 depicted in the parabaik, I had tracked him down. At the time he was managing the U-19's Myanmar football team, as they made their way to the country's first World Cup Tournament. Before that, the man-who-would-be-king had lived a quiet, anonymous existence as a civil servant in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

At first cautious to share his family's story with outsiders, in keeping with decades of experience of living under a military dictatorship, U Soe Win gradually began to open up his world to me. What followed was an extraordinary adventure, taking us across three continents, and back in time across the centuries to rediscover his royal past.

U Soe Win (R), Alex Bescoby (L) & Max Jones (M) filming 'We Were Kings' – credit Grammar Productions

U Soe Win (R), Alex Bescoby (L) & Max Jones (M) filming 'We Were Kings' – credit Grammar Productions

The result was an award-winning documentary– We Were Kings – funded by the Foundation set up in the name of the late, great filmmaker Alan Whicker. The film tells the story of U Soe Win's efforts to reunite his family, and to bring King Thibaw home at last.

The memory of monarchy

Two sets of eyes rest on the far left of the parabaik, where the last moments King Thibaw spent as a king in his kingdom are forever frozen in time.

The exile (or par-daw-mu) is a seminal moment in the country's history. It's been commemorated in Myanmar's literature, art, theatre, film and music, and is still marked every year by his descendants with a poignant ceremony.

The 'Deposition Parabaik' (Or. 14963) – credit British Library

The 'Deposition Parabaik' (Or. 14963) – credit British Library

Dig deeper, and the memory of monarchy is still in the country's bones. The military government drew on royal symbolism to legitimise their position – even building a new capital called Naypyitaw, or 'Abode of Kings'. The monastic orders retain echoes of royal ceremony and language, and young boys dress as little princes before taking the robes for the first time. The political culture of the country – centralised, hierarchical, focused on one or two powerful figures – almost feels monarchic in flavour. The palace in Mandalay remains a potent symbol of royal Burma, and is one of modern Myanmar's most visited sites by citizens and tourists alike.

Across Myanmar today, we see a country grappling with the legacy of an abrupt dismantling of a centuries old institution, a traumatic colonial experience, and rapid decolonisation. Decades of civil war, inter-ethnic conflict, dictatorship and today's religious violence can all in some way find their roots in the events of November 29th 1885.

As U Soe Win and I carefully fold up the parabaik, I catch a last glimpse of Thibaw perched on his throne, and I can't help but think that Myanmar is still haunted by this tiny figure, all in white and gold.

The Pandaw Trust kindly provided the sponsorship needed for the British Library to reproduce the parabaik referenced above in a large exhibition version. This incredible piece of hidden history was displayed at the world premiere of We Were Kings at the British Library on 19th September 2017. The exhibition parabaik will now travel back to Mandalay, for the first screening of the film in Myanmar in November 2017. After the screening, the parabaik will be left as a gift to King Thibaw's descendants and the nation. We're grateful to the Pandaw Trust for helping Grammar Productions bring this hidden history to life.

Alex Bescoby is an award-winning filmmaker, whose life has revolved around Burma for almost a decade. After focusing on modern Burmese history at Cambridge University, he co-founded independent production company Grammar Productions. The next screening will be at the Irrawaddy Literary Festival at the Mandalay Hill Resort on 3rd November.

Discover Royal Burma stopping at Konbaung Dynasty former capitals and sacred sites on the Pandaw II sailing from Rangoon to Mandalay.