Back to Homepage / Blogs / May 2020

Bhamo: City of Rumour

By Paul Strachan, Pandaw Founder

Bhamo, a town on the very frontier of the Chinese enigma, where caravans incessantly come and go through mysterious valleys and where rumours live from day

to day...Joseph Conrad, 1922

Bhamo is the northernmost port for larger ships on the Irrawaddy River and

is almost exactly 1,000 river miles from Rangoon. From the earliest times to

the present day, Bhamo has been a place of unfulfilled expectations. Dubbed by the late Victorian press as a would be 'Chicago of the East', Bhamo had the potential to

be a great inland port that was to dominate a vast Chinese hinterland. Britain was to go to war and annex upper Burma in 1886 partly to prevent the French from accessing these elusive Chinese markets. However, under British

rule in Upper Burma between 1886 and 1942 these ambitions were never realised, and a projected railway never built as stability in China collapsed under the fragmented

rule of warlords during the final days of the Qing and then Sino Japanese wars that began in 1931.

There is again a lot of talk of railways as China implements its 'Belt and Road' policy. In January this year, Aung San Suu Kyi signed an agreement with President Xi

Jinping for the construction of a Rangoon to Kunming high-speed railway. From Momein (or Teng-yueh) on the China border to Bhamo there is now a truck highway, so the

town once again has prospects, being seen as a great entrepot for cargoes and trade through the Irrawaddy corridor and the world beyond. Yet with much of the countryside

around Bhamo in the hands of the Kachin Independence Army or KIA, plus the fact that anywhere north or east of Bhamo is effectively a war zone, this serves to dampen

such Chinese ambitions just as Kachin caterans and Shan-Tayok bandits scuppered British plans for a railway following their 1875 Second Bhamo Expedition and the 'Margary

Affair'.

Marco Polo may have visited in the 1270s when he served as Kublai Khan's ambassador to India and Burma, as he makes reference to the area in his travels, although present day Bhamo, which means Pot Village, in Shan, was probably of little

consequence back then. A few miles upstream at the confluence of the Taiping and Irrawaddy rivers, Sampenago was the old capital of this one-time Shan state, and its

outline can still be traced. Sampenago long commanded the trade route or 'Road of the Ambassadors' from Burma and its seaports to Yunnan and Imperial China beyond. Yet

even at the end of the 13th century, the prospects for trade may have been limited with Pagan's fall in 1278 following Kublai Khan's incursion and the overrunning of

Upper Burma by Shan hoards, as yet uncivilised by the tenets of Buddhism. And by the mid-19th century, the Shan cultivator had been displaced by the Kachin cateran.

Road of the Ambassadors

Bhamo at high water

We do not hear much about Bhamo till Dalrymple writing in 1796 claimed that the East India Company had a 'factory' with Englishmen based there in the early 17th

century, though this remains unproven. We know that King Bodawhpaya settled Assami soldiers nearby at the village of Wethali following his conquest of Assam. Otherwise,

life seems to have continued with a steady trade handled by Chinese merchants sending goods up the 'Road of the Ambassadors'. The outgoing trade from Upper Burma to

China was cotton, and silks were brought back. There are rumours of a Portuguese settlement, and indeed many Portuguese veterans of the king's armies were settled

throughout Burma and given wives and land. Portuguese trading settlements dotted the Burma coasts shipping fine Chinese porcelain back to Lisbon, so perhaps these

fragile cargos were carried by caravan to Bhamo, then shipped down river to the Portuguese ports in the Delta and onward to Europe.

In 1835, Inverness-born Captain Simon Hannay was permitted to travel upriver with the Mogaung governor's party of thirty-four country boats, towed with ropes from the

riverbank. Again, British interest lay in trade with China, but like today, the Kachins were in a state of rebellion and the opening of a trade route was unlikely.

Hannay never reached Bhamo, instead travelling on foot from Mogaung, situated on a tributary of the Irrawaddy, to India.

In 1863, Dr Clement Williams, a British resident in Mandalay and favoured by

King Mindon after performing a successful cataract operation, gained permission to travel upstream. The journey took twenty days, during which time he effectively

surveyed the river whilst being rowed there. In 1868, he returned with the new resident Colonel Sladen (Clement Williams was now the IFC agent for Mandalay) travelling

on the king's new Italian-built steamer the Yeinan Seika, which made the 450 mile journey in just eight days and established the river's navigability one thousand miles

from the sea. Sladen was able to join a mule caravan as far as Teng-yueh, 135 miles from Bhamo and thus established the possibility of a trade route to China. King

Mindon was keen to increase trade, even if this meant teaming up with the agency of the British and their flotilla company. A treaty had been signed in 1867 enabling the

British to set up a residency in Bhamo and allowing a steamer service.

Captain GA Strover was appointed 'resident' and sailed up on Colonel Fytch, the first IFC steamer to reach Bhamo. He travelled with a 'trade mission' of

Rangoon merchants, mostly Scots, keen to see the possibilities for themselves. J Talboys Wheeler made a similar journey to visit Strover in 1871 and describes the lonely

captain, bereft of bread, tea, cheroots and the company of Englishman for seven months. Talboys Wheeler was, though, extremely optimistic towards the commercial

prospects and on his return to Mandalay was interviewed by the king, who was keen to open up for trade. Soon after the 1868 First Bhamo Expedition, the IFC inaugurated a

monthly service from Mandalay to Bhamo and the ships and their flats were soon laden with the entire Upper Burma cotton crop to be transhipped by mule across the

mountains to Yunnan. By the 1870s, Chinese merchants were sending 1000 mules a month to China, such was the increase in trade volumes.

From 1860 to 1874, Yunnan was in the hands of the Moslem Panthays who had rebelled against Beijing. In fact, British contacts in Yunan were with the Panthay rather

than the imperial administration and the Panthays themselves were keen to trade with the British. In 1872, Crown Prince Hassan travelled through Burma to visit London in

the hope of kindling support (which he failed to gain). On his return journey whilst at Constantinople, he learnt of the Fall of Talifu and death of his father, ending

the rebellion. Yunnan was in Panthay hands, meaning that British trade had not yet penetrated properly into China. Following the fall of Talifu in 1874, a Second Bhamo

Expedition was organised, this time in conjunction with the Beijing government. A 'Shanghai Party' under a diplomat, Augustus Margary, would set out from the Chinese

side to meet up with Colonel Horace Browne from the Burma side. Margary reached Teng-yeuh early and decided to reconnoitre the route without sufficient escort. He and

all his party were murdered by Shan-Tayok tribesmen who believed they were there to survey for a railway, which was against their interests. Browne and his party were

similarly ambushed coming up from the Bhamo side, but escaped back to Bhamo with the remnants of the Shanghai Party, all returning to Mandalay by steamer. This became

known as the 'Margary Affair', which developed into an international incident which enabled the British to enforce an indemnity paid to Margaray's relatives and the

concession of treaty ports from the Chinese under the Chefoo Convention of 1876. The 'Margary Affair' set back British plans considerably, as black reports came in from

the follow up expedition sent to investigate the murder. Enthusiasm for a railway waned. Prior to this, no one had considered the lawless nature of the country, with

its uncontrolled dacoity and the vested interests of the tribes people, whether the wild Kachin wielding their dah (swords) and permanently engaged in

vendettas, or Shan-Tayok bandits exacting tolls and protection payments. Really much the same as today!

Throughout the 1870s there had been a considerable lobby in England to open a railway, mainly at the instigation of Captain Richard Spyre, a retired India Army

officer. The Manchester Chamber of Commerce and the various other chambers across Britain took up the call and lobbied the government incessantly to progress this

project. In 1860, The Times concluded "by confining our trade to the southern and eastern seaboard of China, we are but scratching the rind of that mighty

realm. The best Chinese products, and customers for our products all lie inland towards the west". As previously mentioned, the 'Margary Affair' dampened enthusiasm. In

many respects, the lobbying of the chambers of commerce for a Burma China railway was a forerunner for their lobbying for final annexation – an annexation which, when

finally achieved in 1886, was not intended to deliver them the markets of Upper Burma, but those of China. Interestingly the British never gave up on the railway idea

and there were various surveys up until the First World War. By the late 1930s, all China's seaports were in Japanese hands supplying inland China with materials through

a Burma corridor, and the Burma Road, completed in 1938, was a similar concept. Today, under China's 'belt and road' policy, the Burma corridor strategically circumvents

a shipping choke point in the Malacca Straits, whether for oil and gas pipelines, truck super-highways, high speed railways or great barges bound for Bhamo.

Clement Williams describes Bhamo in 1863 as a sad sort of place. As a result of Kachin raids, many of the Shan villages with their orchards of orange trees had been

abandoned. The town itself had recently suffered a fire – apparently it was a tradition that the myo-sa or 'town eater' (the Mandalay appointed governor) would

burn the town down at the end of his tenure to despoil it for his successor. Although there were lead and silver mines, they were no longer worked due the depredations

of Burmese officials — it was not worthwhile. The Chinese merchants, with their godowns filled with bales of cotton, sat idle in their shop houses waiting for Yunnan

caravans that never arrived, disrupted by Kachin raids and the Panthay rising.

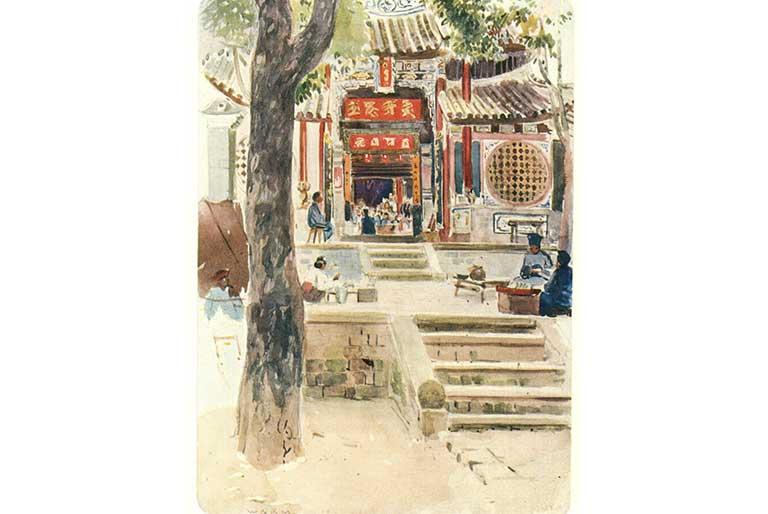

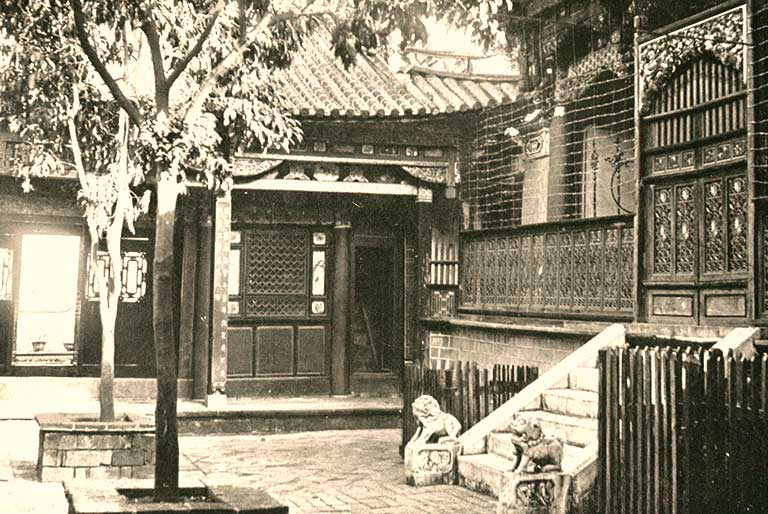

Early sketches of the town show it as more Chinese than Burmese in appearance and nearly all early accounts describe the temples, that seemed to double as casinos,

and splendid merchant's houses with their inner courtyards. Sadly, these are now all gone, and modern temples have been constructed on the sites of ancient 'joss

houses', as they were known.

Joss House, Bhamo by WG Burn Murdoch

Innner Courtyard of a Joss House, 1904

Following the death of King Mindon in 1878 and the accession of his son Thibaw with the 'massacre of the princes' — half siblings were placed in velvet sacks and

pounded to death – Burma-British relations took a turn for the worse. Corruption and bureaucracy took over, whilst anarchy reigned in the countryside and order broke

down. One of the IFC's most famous captains, a Dane called Terndrup, recounted to Hugh Fisher that following a Kachin rising in the early 1880s, he witnessed thirty

Kachin tribesmen drifting down river from Bhamo nailed to crucifixes. In 1884 as commander of the Kha Byoo, Terndrup steamed into a burning Bhamo and personally

negotiated with a Chinese warlord who had taken the town for the evacuation of the British and Americans stranded there – for which the captain was awarded a gold watch.

Of Icelandic origin, a young Terndrup ran away to sea from his family farm in Schleswig Holstein when the Prussians invaded. He became commander of the flotilla until

his death in 1919 aged seventy — thereafter the company introduced a retirement age.

During the 3rd Anglo Burmese War, Captain Redman was despatched to Bhamo to evacuate any remaining foreigners. However, his ship, the Okpho, was captured at

Moda and he and his officers were taken as prisoners to Mandalay where they were cruelly subjected to mock executions. There's clearly far more to being an Irrawaddy

commander than simply navigating ships.

By the 1890s following the annexation of Upper Burma, there was a sizable European community in this frontier post. The Irrawaddy Flotilla Company agent was a

position of some importance and a Bourbon exile, by the name of d'Avera, formerly a minister in the service of King Mindon, took up the post. The IFC agent of any port

was the centre of intelligence gathering and business activity as everything and everyone passed through their hands. IFC agents were the unofficial consuls of empire.

In 1911, Hugh Fisher described d'Avera himself as something of a tourist attraction among American globetrotters, who gathered around him. Interestingly, the main

tourists to Burma in this period seem to have been Americans on imperial tours; a cruise up the Irrawaddy ranked up with the Taj Mahal and Ghauts of Benares as an

essential component of a tour of the East.

Around the turn of the 1900s, several travel writers passed through, either on their way to or from China or as part of a Burma tour. RF Johnston quotes a Dr Morrison

of 1894:

There is a wonderful mixture of types in Bhamo. Nowhere in the world… is there a greater intermingling of the races. Here live in cheerful promiscuity

Britishers and Chinese, Shans and Kachins, Sikhs and Madrasis, Punjabis, Arabs, German Jews and French adventurers, American missionaries and Japanese

ladies.

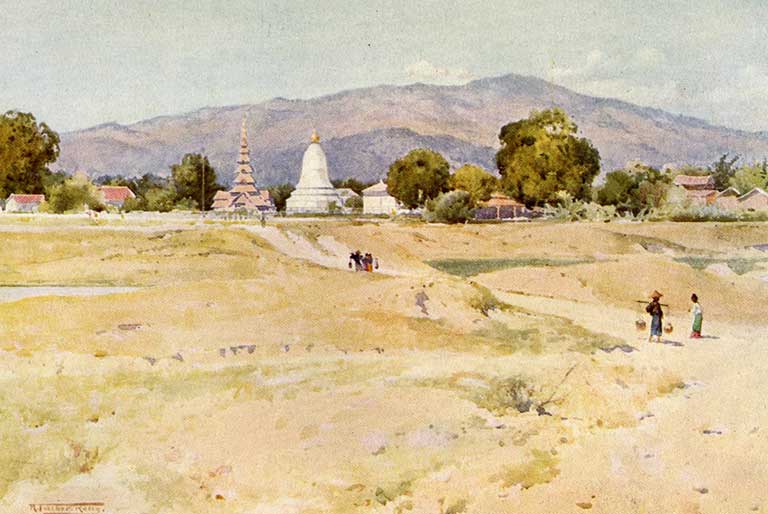

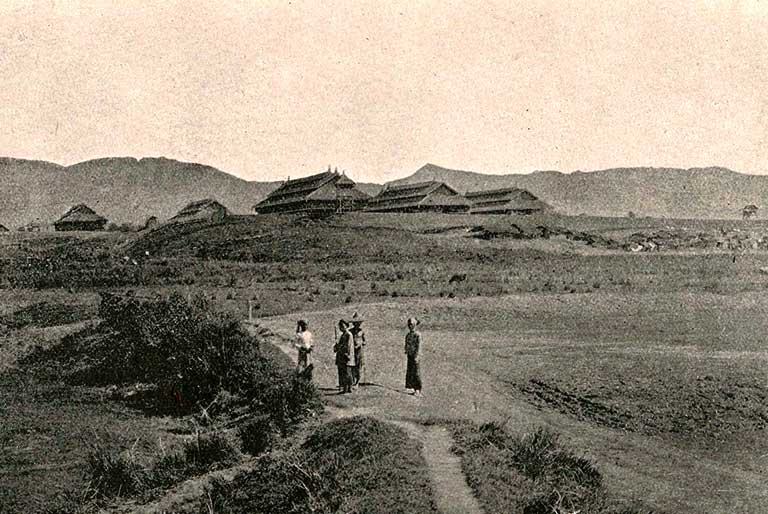

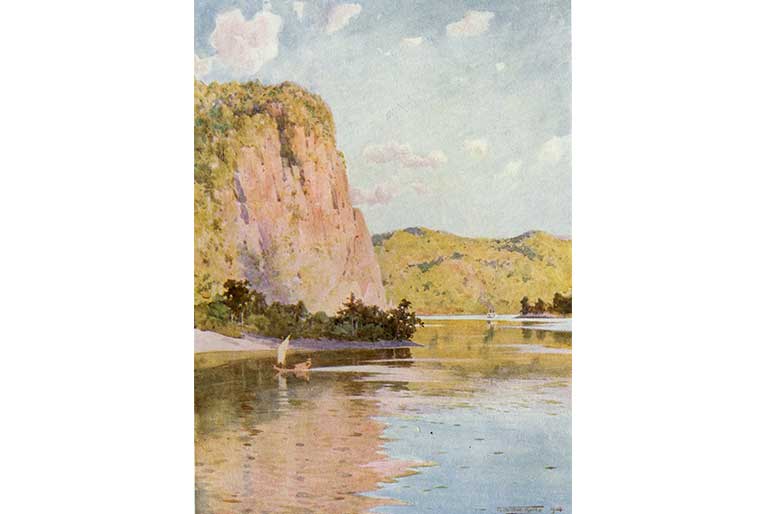

Bhamo from the fort, c.1905, by R Talbot Kelly

The fort, Bhamo, c 1897

Johnston found Bhamo much the same when he visited in 1908 only "the French adventurers and Japanese ladies had fled to other pastures".

In 1904, Scott O'Connor wrote "Bhamo like the river on which it is built leads a double life". Arriving today by boat, the strand road remains much as it was when

Scott O'Connor visited with teak bungalows along the riverbank shaded by great rain trees. You can still find the IFC agent's house, now the office of Inland Water

Transport or IWT. Inside the town, little of what Scott O'Connor describes remains. Back then it was a typical old Chinese town of wooden shop houses and splendid

merchant houses. Now it is a typical modern Chinese town of ugly concrete frame blocks, often clad with blue mirror glass. The 'Indian Street', once filled with Indian

tailors has gone, though there are still plenty of Indians around, not to mention Gurkhas and various others left behind from the empire. Armenians are there too, long

predating the British in Burma as bankers to the Burmese crown. (I was to meet remnants of these communities in the countryside outside Katha in the 1980s – their house shrines, just where the family Buddha would be in any

Burmese home, filled with glimmering icons). The Bhamo billiard saloon was kept by a Jew and the fort was garrisoned by Sikhs in splendid red turbans. A German called

Kohn ran a sort of department store where you could buy anything. American Baptist missionaries were arriving in force, their sights set on the unruly Kachins, and no

doubt the Japanese geishas had been replaced by ladies drawn from less distant lands. Scott O'Connor, as always, says it all:

A Sikh sentry, with bayonet gleaming in the sun, walks to and fro before the treasury; in the litigant's shed the witnesses are assembled; on the grass of

the courtyard the harnessed mare of the Deputy Commissioner feeds complacently, aware of her privileges. Burman's in silken kilts and flaming headgear, Shan in loose

trousers and big straw hats, come and go in an incessant leisurely stream. And out on the white high road a British soldier swings by, his shoulders square, his boots

creaking, the silver head of his regimental cane glinting in the sun.

The IFC ran an occasional steamer service for the final 220 miles to Mytikyina through to the late 1890s, which must have been quite an adventure, navigating in the

First Defile through boulders the size of apartment blocks. George Bird made this passage in 1897 and his account in his Wanderings in Burma remains the best

description of the route. At Sinbo where the river is just three hundred feet across, there were records of ninety-foot rises at the onset of the monsoon. Scott O'Connor

mentions a rise of fifty foot overnight and during the rainy season, a country boat would take three weeks to travel upstream to Myitkyina and six hours to travel back

down! In 1896, the Mu Valley State Railway that had run as far as Naba with a branch line to Katha was extended to Mytikyina and thereafter there was little need for a

steamer service running in such risky waters.

The Bhamo bazaar c 1905, by R Talbot Kelly

The First Defile, c.1905,by R Talbot Kelly

D'Avera's successor as IFC agent was Captain Medd who had served with the Flotilla since 1892 and was appointed Bhamo agent in 1911, where he remained until his death

in 1930. Writing in 1973, Captain Chubb recalls meeting him in the early days of his service: "he was a gentleman of the old school". Medd's office must have been

something of a museum and Chubb recalls seeing early IFC house flags hanging on the walls. Major Enriquez describes Medd in his wonderful book about the Kachins, A

Burmese Arcady (1923):

D'Avera's successor as IFC agent was Captain Medd who had served with the Flotilla since 1892 and was appointed Bhamo agent in 1911, where he remained until

his death in 1930. Writing in 1973, Captain Chubb recalls meeting him in the early days of his service: "he was a gentleman of the old school". Medd's office must have

been something of a museum and Chubb recalls seeing early IFC house flags hanging on the walls. Major Enriquez describes Medd in his wonderful book about the Kachins, A

Burmese Arcady (1923):

Medd was the source of the Conrad quote that started this article. Conrad never visited Bhamo but wrote the preface to his friend and literary agent Richard Curle's

travel book on Burma and Malaya and picked up on the mystery of the place. Curle tells of his encounter with Medd:

I found awaiting me there in Bhamo the agent of the IFC; a man replete with knowledge, who illumined for me later in one sentence something about Bhamo I had

instinctively felt since the first moment. "On the frontier" said he, "we live on rumours".

In 1904, Scott O'Conner visited Sinlum Kaba, a hill station 6,000 feet up in the mountains above Bhamo. Established by NG Cholmeley of the Indian Civil Service, there

were gardens with peach and cherry trees from England. Sinulum Kaba, rather than Bhamo became a centre for justice for the Kachin, far from thieving lawyers and the

inflexibility of a district court. Kachins would come in and have their cases heard in a humane and sympathetic way. Under a sense of fair play projected by British

administrators and with no intention to strike a fatal blow with their dah, a peace settled over these hills that had never before been known.

Walter G Scott was the assistant superintendent at Sinlum Kaba who first promoted the idea of Kachin levies serving with the Burma Rifles during the First World War

and seems to have introduced the bagpipes to this highland people. Enriquez believed that the experience of the Kachin levies in the First World War was far more

effective than fifty years of administration. Duwa Scott died of dysentery at Sinlum but was remembered by Kachins for generations to come, and the Kachin

regimental pipes still bear the Scott tartan in his honour.

Kachins at Bhamo, 1930s

Kachins at Bhamo, 1930s

Enriquez had recruited and trained Kachin troops in the First World War, travelling with them from Bhamo to distant Mesopotamia where they served with the Burma

Rifles with great distinction. On the soldier's return from the war, with years of pay saved up, the bazaars of Bhamo were emptied of gongs – the ambition of every

Kachin being to own one. Never before had there been such an influx of cash into the Kachin economy.

Enriquez had a vision of the possibilities of taming the wild Kachin and sending them off around the world to serve, rather like the Nepali Gurkhas. In recognition of

their bravery and discipline, the Kachin Rifles was formed shortly after the First World War, the idea being to channel the Kachin's warlike tendencies to the empire's

benefit. At the same time, the Kachin's were being tamed by other means. American Baptist missionaries (though there were Roman Catholic missionaries too) were

extraordinarily successful in subduing the Kachin where Burmese kings and British military expeditions had failed.

And here we are one hundred years on, and the Kachins are still at war, once again with the Burmese after an all too brief sixty-year Pax Britannica and an even

briefer honeymoon with a newly independent Burma in the 1950s. In 1960, the Burmese leader U Nu declared Buddhism as the state religion: this antagonised the

predominantly Christian Kachin and drove them into open rebellion. A large number of the Burmese army were Kachin who split and formed the Kachin Independence

Army. Fighting between the KIA and the Burmese army continued until 1994, when there was a seventeen-year truce. This was broken by the Burmese in 2011 and war continues

to this day. Kachin State is rich in resources, the most famous of which is jade, but also in water resources with the headwaters of Burma's great rivers rising there.

The Chinese are keen to get their hands on both the jade and the rivers, with plans for hydro-electric schemes that would flood areas the size of Yorkshire; all that

power would flow north, not south.

During the colonial period, Bhamo attracted a number of sportsmen, and it was agreed that sport in Burma was as good as in Africa. Nearly all colonial accounts

describe duck shooting along the river's sandbanks, fowling in the jungle or big game hunting for tiger deep in the forest. WG Burn Murdoch in From Edinburgh to

India and Burmah amusingly describes pistol shooting otters on the riverbank – yet this perhaps helps explain why there are no otters left there. Dolphins have

survived to date, and on one occasion sailing up towards Bhamo on the Kalaw Pandaw, we were escorted for many miles by a pod swimming just to the fore of the bow. When

the unthinking captain took a wrong turn and landed us on a submerged bank, the dolphins swam around as if in admonishment. If only we had followed their lead – they are

the surest pilots on the river.

If you strike lucky when cruising up the river, you might see a leaping golden mahseer. This migratory fish is known as the Himalayan salmon, but is much larger,

growing as big as 50kg and up to 2.75m long. In colonial times, anglers travelled to Bhamo specially to fish these monsters in the First Defile, and even built a club

house nearby.

I finally made it to Bhamo in the early 2000s after being thwarted in the 1980s by military engagements and in the 1990s by underpowered ships. The then brand new Pandaw II with her powerful Caterpillar engines made it in high water without too

much difficulty and we were able to go up to the spectacular First Defile by country boat. We were back a couple of years ago and when we set out for the First Defile,

we discovered that the KIA now had machine gun nests guarding the river at the entrance to the gorge. On one occasion we were late returning to town following a boat

trip upriver to see the Taiping confluence. Due to low water, our ship was moored ten miles downstream and as dusk fell, we were told that we could not return as the

roads were unsafe, being under the control of the KIA. After much negotiation we persuaded the police to let us go back down river by boat with an armed escort. This

brought home the fact that the Bhamo has become a Burmese island in midst of KIA sea, with little or no control over surrounding roads or countryside.

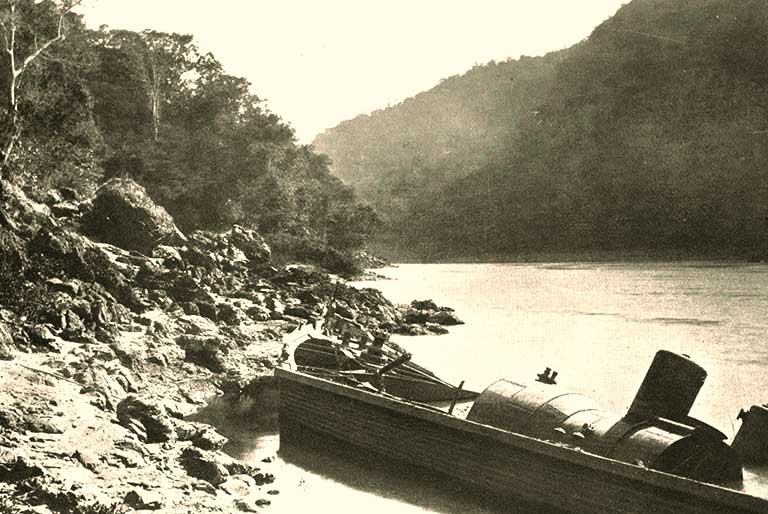

Wreck of King of Burma's steamer in the 2nd defile.

Kalaw Pandaw near Bhamo

Even though one government-owned P-class steamer was mortared and sunk by the KIA in the six hundred foot deep Second Defile in the 1960s, the river route remains

open and safe today. We take our intrepid travellers up to the Second Defile but no further, not because we are not allowed to, or we think it dangerous, but because

there are foreign ministry advisories against overland travel to Bhamo and travel agents would have their insurance cover nullified. A couple of years ago we were

contacted by friends in the government and asked to lend them a ship for high level peace negotiations between the NLD and the KIA at Shwegu. It is nice to think that a

soothing cruise on a Pandaw might have brought the two sides closer to peace.

It would be great if we could sail to Bhamo again. Even if the town is not as beautiful today, the trip certainly is, and Bhamo's surroundings are full of interest

and very pretty. There are lots of flights now from Bhamo to Yangon so we could easily turn ships round there. I have lobbied the British FCO to change their advice on

the river route being unsafe, without success. Perhaps one day that will change, and we can go back. Once again, it all comes down to rumour.

Further Reading:

Clement Williams. Through Burmah to Western China. London, 1863.

RF Johnstone. From Peking to Mandalay. New York, 1908.

J Talboys Wheeler. Journey of a Voyage up the Irrawaddy. Rangoon, 1871.

VC Scott O'Connor. The Silken East. London, 1904.

George W Bird. Wanderings in Burma. London 1897.

Major CM Enriquez. A Burmese Arcady. London, 1923.

A Hugh Fisher. Through India and Burmah with Pen and Brush. London, 1911.

Richard Curle. Into the East: Notes on Burma and Malaya. London, 1923.

WG Burn Murdoch. From Edinburgh to India and Burmah. London, 1908.

Captain HA Chubb and CLD Duckworth. Irrawaddy Flotilla Company Limited 1865-1950. London 1953.