Back to Homepage / Blogs / May 2020

The Irrawaddy Commander

By Paul Strachan, Pandaw Founder

To captain an Irrawaddy ship is no small challenge. Still without charts and few navigational aids, little has changed for

our 21st century captains compared with those of the previous two centuries of ship navigation on the rivers of Burma. The

only thing that counts is experience and a calm, collected mind. Our Pandaw fleet commodore, Captain Maung Maung Oo certainly

has those qualities and many more besides. At the age of fifty-four, he has enjoyed a career not untypical of most present-day Irrawaddy commanders. From a village near

Myingyan close to the banks of the Irrawaddy, he comes from a long line of rivermen and his father was an Inland Water Transport (IWT) commander before him. Captain Oo

joined the IWT at eighteen years old and had his master's ticket by the age of twenty-one. He initially skippered smaller vessels and was then promoted up through the

government fleet to command the larger 'line' ships. Leaving government service, he joined Pandaw in 2001 and currently commands our largest ship in Burma, the Orient

Pandaw. As commodore, Captain Oo takes care of the other captains in the fleet with training and support. Like all our masters, he has adapted from carrying cargo and

local deck passengers to world travellers and has had to brush up his social skills and learn a smattering of English to explain navigational matters to visitors to his

wheelhouse.

Captain Oo follows a long tradition of Irrawaddy commanders going back to the days of the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company first established in Burma in 1864, when nearly

all the captains and officers were Europeans, with many Scots, and the engineers almost exclusively Scots, whilst the crews were Indian Lascars. As Captain Oo finds

today dealing with both strange foreigners and irascible officials, there is far more to be a river boat commander than being a good skipper: diplomatic skills are

essential.

Captain Maung Maung Oo

Captain Maung Maung Oo onboard the Orient Pandaw

Little is known of the early commanders from the time of the flotilla's arrival as a naval task force in the 2nd Anglo Burmese War of 1852. A Captain Sevenoaks joined

the company from the Indian Navy when his ship was sold to the company in 1864, and there is a Sevenoaks Channel near Thayetmyo that must have been named after him. Nearly all records of those early days were lost either during the Japanese occupation of 1942, or the work of

ants following the nationalisation of the company in 1948.

In 1864, the four Indian Navy paddle steamers used in the war were sold off to a trio of Scots businessmen: Todd Findlay who were long established merchants in Burma;

Denny's of Dumbarton who were ship builders; Paddy Henderson who ran ships from Glasgow to Rangoon. Dependent on a mail

contract, the newly formed Irrawaddy Flotilla Company had a shaky start and it was not until the 1870s that the possibilities of running a great river enterprise were

realised. A new company was formed which floated on the Glasgow stock exchange in 1876 and numerous new vessels were ordered from Denny's yard in Dumbarton.

The IFC enjoyed good relations with King Mindon and ran regular steamer services between Rangoon, capital of British Lower Burma and Mandalay the capital of Royal Burma. The IFC agent at Mandalay was a figure of some importance, a focus of business interests and intelligence. The first

agent, Dr Clement Williams, had previously been Resident, then became equivalent to a consul, before resigning to take up the position as company agent at Mandalay.

Williams was close to the king, having carried out a successful cataract operation on him. He was followed as IFC agent by the Italian consul, Cavalliere Giovanni

Andreino, who stayed close to power during the dark days of Thibaw and Supayarlat. Thanks to Dr William's diplomacy, IFC services were extended to Bhamo in 1868 and the Chindwin around the same time.

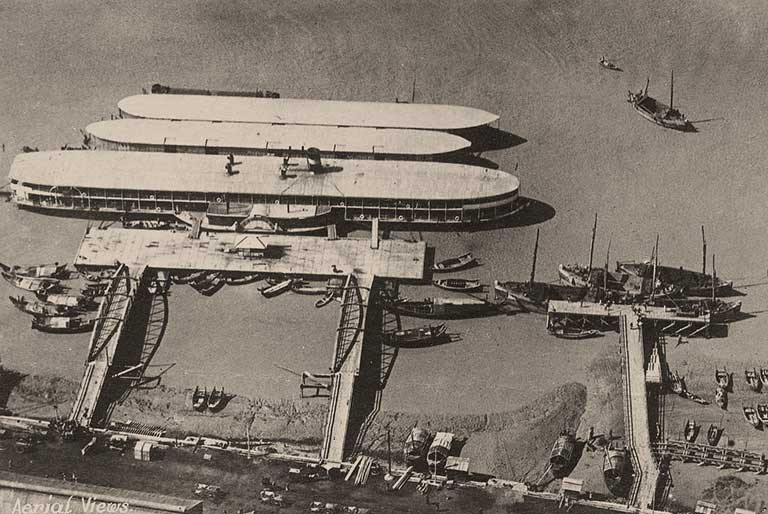

Ariel view of steamers on the Rangoon River

Scene from the Rangoon River

A number of dynamic captains emerge during this period. There was a famous silk shop in Mandalay whose sign read "By Appointment to the King and Queen of Burma and

Irrawaddy Steamer Captains" such was their prestige. By 1884, the company had grown to thirty-one steamers and sixty-five flats. The largest like the Mindon and

Yoma were 300 feet long and could carry 3,000 passengers, 500 tons of cargo and an additional 1,200 tons of cargo in two flats lashed either side.

We know of the Danish Captain Jan Terndrup who at the age of twenty-four commanded the Kha Byoo, the first of Denny's ultra-shallow draft steamers designed

for the upper rivers. The family, apparently of Icelandic origin, were settled in Schleswig Holstein. At the age of fifteen, on the Prussian invasion of 1864, Terndrup

ran away to sea and somehow ended up in Rangoon where he joined the flotilla. Steamer captains at that time were glamorous figures, as they are still, and this handsome

young Dane caught the eye of Queen Supayarlat and became a favourite at court until the king put his foot down.

In 1884, it was Terndrup who was sent up to Bhamo on the Kha Byoo to rescue the expat community when a Chinese warlord invaded, evacuating six hundred

Europeans after personally negotiating a cease fire with the Chinese commander. The government awarded him a gold watch for his efforts. Hugh Fisher recalls meeting him

in 1911 when Terndrup recounted to him the atrocities committed by the Burmese against the Kachins, describing over thirty crucified Kachins floating down the river.

Writing in the 1970s, Captain Chubb recalls him as young man sailing with him on the PS Nepaul in 1919. By then, Terndrup had become flotilla commodore where he

remained until he retired at well over seventy years old; thereafter the company decided to bring in a retirement age of fifty-five.

In October 1885, it was Captain Cooper who was sent up from Rangoon on the Ashley Eden to deliver the ultimatum, and his ship stood off Mandalay with banked

fires whilst he delivered it to the palace. Clearly it was preferable to use a man who was known at court and could access the king. In the following year, Cooper hit a

rock off Minbu and sank whilst commanding the Thoreah. Despite this, he was later promoted to marine superintendent.

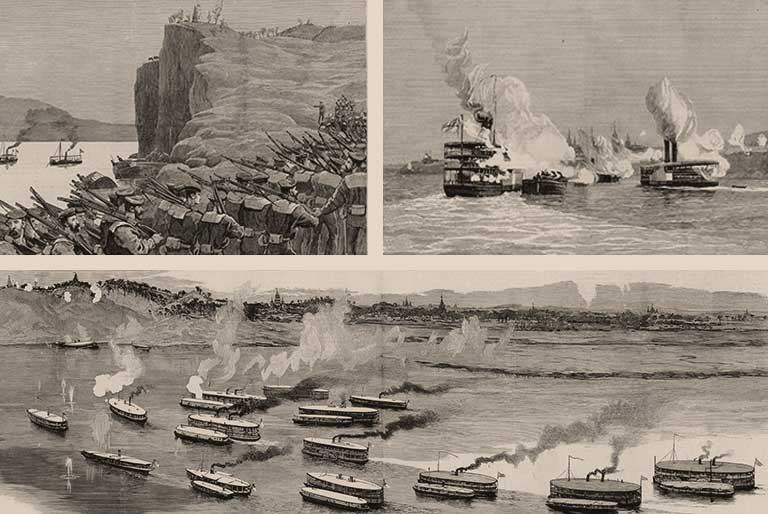

During the 3rd Anglo Burmese War, flotilla commanders took an active role in the campaign. The fleet had been requisitioned, the steamers armed, and flats fitted out

as mobile barracks. The triple decked Thoreah with her flats alone transported 2,100 men up-river. Altogether, General Prendegast's army of 10,000 with 7,000

followers were transported upriver to Mandalay with barely a shot fired. The only serious engagement was an attack on the Italian-built Gwechaung and Minhla forts that

guarded the Irrawaddy just north of the border at Thayetmyo which were outgunned by batteries on the flotilla ships manned by the Royal Navy.

Meanwhile, Captain Redman on the Okpho had been despatched to Bhamo to rescue the Europeans there, but was captured at Moda and taken to Mandalay where he and his

officers were subjected to several mock executions. Only the intervention of the IFC agent Andrieno saved them.

Scenes from the 3rd Anglo Burmese War, 1885

The Palow with flats, c.1900

Captain Terndrup acted as a guide to the British forces and it was Captain Morgan who escorted Colonel Sladen into the palace to interview the king. Irrawaddy

commanders knew how to move around the palace city subtly and there was no need for force. Finally, on 29th November 1885, the royal family was escorted on board the

Thoreah under Captain Patterson who took the royal party down to Rangoon, where the king and queen and their children were transferred to the RIMS

Clive to sail to Madras and then on to Ratnagiri, where they were to live out the remainder of their lives in exile. The Queen Mother and Queen Supayargyi were

exiled to Tavoy, far on the south coast. A further forty-one princes and princesses were later carried to Rangoon later in December on the Alaungpaya and

settled there on government pensions. The normal messing allowance on board for company officers was one rupee a day, but Captain Patterson claimed Rs10,000 for

entertaining the royal party.

Captain William Beckett had escaped from Mandalay on the Palow at the outbreak of the war, flying a royal peacock flag handed to him by Andrieno who

visited the ship in disguise late at night with a warning. Dressing up his clerk as a Burmese wun or official and sitting in full rig at the fore of the ship,

he appeared as a Burmese prize and sailed off unchallenged to run the gauntlet of border forts back to British territory. The Palow was fitted out with guns and

manned by Royal Navy gunners; with almost Elizabethan bluster, Beckett came up-river firing broadsides at the royal forts.

Beckett seems to have been something of an institution in the flotilla and stories of his eccentricities abound. Shortly after the searchlights were installed for the

first time in 1889, Beckett crept up on Thayetmyo and simultaneously sounded his horn and switched on his searchlight, which was turned on the town. Fearing a

beloo or monster, the populace took fright and ran away into the jungle. Clearly, he was in favour of searchlights and after their introduction insisted on

sailing by night and remaining moored up all day. With a taste for pyrotechnics, perhaps acquired in the 3rd War, he was famous for firing off a brass canon each time he

sailed into port. Perhaps he is best remembered for 'Beckett's Bluff' near Magwe where he had managed to lose a flat in deep water. There's no doubt that Beckett's Bluff

continued to cause chuckles amongst fellow captains for years to come. A number of other features on the river are also named after embarrassing moments, such as

'Macfarlane's Folly'. However, Beckett's most enduring legacy was the 'Beckett Buoy'; an ingenious arrangement of sandbag, line, and a bamboo pole with an old condensed

mill tin fixed to the top, with its upended lid acting as a reflector that could be spotted miles away. Given the expendable nature of the materials used, they cost

little to make, yet for years saved much time and money in unnecessary groundings.

Most IFC captains were less flamboyant than Beckett and probably rather dour characters habituated to spending sixteen hours or more each day at their post whilst

never losing a second's focus. These seemingly unmanoeuvrable monsters, 300 foot long and half that wide when towing flats, would entirely fill channels while there were

hazards all around – rudderless teak rafts with entire villages on them drifting down; loose logs clanging into the hull and endangering the paddles; fishing nets strung

out across the channels; canoes at night, whose single navigation light would be the oarsman's whacking great cheroot.

In 1888, Captain Clausen spent three days on the Kha Byoo in a whirlpool in the Second Defile and his hair turned white. Such whirlpools were not uncommon

during the monsoon floods. In the low waters of the dry season, groundings were frequent, as they still are today. Most captains could wriggle off using the paddles to

displace sand. If that failed, ships dropped kedging anchors and winched them off or, if the situation was particularly bad, got help from one of the super shallow draft

(2ft!) IFC tugs that patrolled the river laying buoys. There were several instances of long-term groundings, such as the Momein that was left high and dry for

nearly a year in 1919. In such cases, their commanders were required to stay on board until they floated off. There are stories of captains cultivating little gardens to

grow vegetables in the lee of their ships. In 1904, VC Scott O'Connor wrote:

Some of the steamers that come this way are of the largest size; mailers on their way from Mandalay; cargo boats with flats in tow; laden with the produce of

the land; and when they come round into the view of Maubin, the great stream shrinks and looks strangely small, as if it were

being overcome by a monster from another world. Three hundred feet they are in length, these steamers with their flats in tow, half as wide, and they forge imperiously

ahead as if all space belongs to them, and swing round and roar with anchor chains, while the lascars leap and the skipper's white face gleams in the heavy shadows by

the wheel — the face of a man in command.

And when you see this wonderful spectacle for the first time, you step on board this great boat expecting to

find an imperious man with eyes alight with power, and the consciousness of power and the knowledge that he is playing a great part. But you are disappointed, for you

will find a plain man, very simple in his habits and ways with weariness written about the corners of his red eyes. Ah! They know their work these men… And I say nothing

of the Clydesman who rule the throbbing engines...

As the company grew, captains tended to be recruited in Scotland and sent out to Rangoon where they would spend a year as a second officer on a main line steamer and

then a chief officer on a smaller ship. They then sat the exam for the 1st Class Inland Master's Certificate and if they successfully passed it, were appointed to their

own command and higher pay. There were additions to pay for passing language exams in Hindi necessary for dealing with the Indian crew, and Burmese for communicating

with passengers. All commanders came from a sea faring background, as did the other European officers. Main line steamers had a European commander, chief officer and 2nd

officer and chief 2nd, 3rd and 4th engineers. Smaller ships had a European commander and engineer.

The deck crew on all ships were almost entirely Chittagonian Lascars under a sarang, most of the crew being his kinsman, or at least from his home village

usually in the Cox's Bazaar area of what is now Bangladesh. When he transferred to another ship, the crew went with him. Many Lascar words are still used by present day

Burmese rivermen, such as sukani for the helmsman, who is now more a chief officer and a particularly important man. Smaller vessels such as the Delta creek

steamers were commanded by Chittagonian masters. Pursers on the larger ships tended to be Burmese clerks and as with the Burma railways by the 20th century, Anglo

Burmese engineers were taking over from the Scots who had mainly come from the Dumbarton area, having served their time in the engine works at Denny's.

Captains were well paid and received a 2.5 % commission on a vessel's earnings; a powerful incentive to ensure efficient loading to increase cargo tonnage and make

sure everyone had a ticket. However, damages were deducted from this, which made them very careful. One captain broke the mirror of his searchlight and rather than pay

for a new one, acquired a replacement from a bar in in Rangoon. When the light came on, 'Younger's Indian Pale Ale' was flashed up in brilliant technicolour on the

passing riverbanks. A teetotalling company director out from Glasgow happened to be on board and made a fuss, and the captain was forced to replace it. The company also

had a very generous provident fund that provided healthcare and insurance. There were officer's clubs in Rangoon and Mandalay and a company newsletter called 'Flotilla

News' kept everyone in the loop. There was even a company football league which was based on the Scottish league with teams of company employees from the different

offices with names like Bhamo Rangers, Pakkoku Thistle etc., though there were murmurings from head office in Glasgow about the teams travelling up or down river to away

games gratis.

Irrawaddy commanders were provided with a valet to ensure that uniforms were pressed and laundered. EM P-B describes her husband rising at four and never having time

to change out of his pyjamas, keeping a uniform jacket handy for when passing other ships. EM P-B wrote the best account of the life of an Irrawaddy captain in her Year

on the Irrawaddy published in 1911. I do not know her full name, but she was the wife of the captain of an oil steamer. The 'Skipper' as she always referred to her

husband would be at the wheel for twenty hours a day drinking coffee and smoking cigarettes. Describing the skipper at work, the tension is palpable:

Picture for yourself a vessel of tremendous beam with an equally broad flat on either side streaming through a zig zag channel scarcely wider than the

steamer and flats, with a hurrying tide helping them along and tantalizing little boats scudding across the pathway. Imagine what endeavours are needed to prevent the

flats smashing into the banks they swing round a sharp corner. Think of the accumulated difficulties when the Commander sees a similar vessel bearing down on him from

the opposite direction and a warning "by your leave" from another ship overtaking him and you will get some faint idea of the state of mind of the skipper as he steers

his vessel through the creek.

These oil ships towed flats of crude oil from the oil fields at Yenanchaung to the Burmah Oil Company refinery at Syriam

near Rangoon. Given their inflammable nature, they were not allowed to go alongside other ships at the ghauts and had to moor midstream. It was a lonely life for the

captain so unlike the captains of other ships, his wife was also allowed to live on board. Other captains had their wives in Rangoon lodgings. There was a famous one run

by a Scots widow where these lonely ladies awaited their men's return, which for an express steamer captain would be roughly every three weeks. There were good moments

though. EM P-B describes being tied up for the night on a remote riverbank with a group of other ships and the captains getting together round a saloon piano to sing sea

shanties until late in the tropical night.

Seven of the 300 plus foot mainline steamers plied the 'express' route from Mandalay to Yangon with two departures a week from either end and each taking a week, plus

at least three days at either end for loading and unloading. The use of flats, which could be dropped and unloaded/reloaded in their own time, hugely reduced inefficient

time tied up. Although there was a railway with a sleeper service from Rangoon to Mandalay, many people preferred to go by river simply because it was such fun. A friend

who had grown up in 1930s Burma told me that when the 'government' moved to the hill station of Myamyo during the summer heat, most 'official' families opted to go by

steamer as it was something of a pleasure cruise through the colourful heart of the country. Nearly all travel writers commented on the excellence of the accommodation

and messing on board. First class cabins, of which there were about a dozen on the main line steamers, were on the forward section of the upper deck with an open

observation deck to the fore and a saloon running down the middle onto which the cabins opened. Madrassi butlers served them and meals followed the Anglo-Indian pattern

of a big late breakfast, afternoon tea or tiffin and a dinner served quite late in the evening. The 3,000 or so deck passengers sat on their bundles of luggage

picnicking or visiting a canteen in the aft section.

In addition to taking care of officials travelling on business or leave, the Irrawaddy captain would be required to entertain early tourists. These were mainly

American 'globetrotters' who visited Burma in considerable numbers from the 1900s onward. Then there were the state visits of viceroys and members of the British and

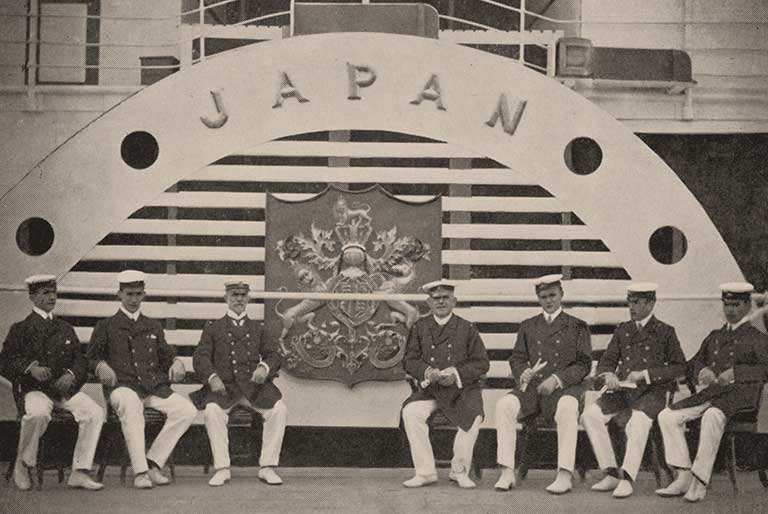

other royal families. On these occasions, the hull would be painted white and the funnel yellow. The future George V and Queen Mary, as Prince and Princess of Wales,

travelled on the Japan in 1906 and can be seen in the attached photograph. It was said that the prince was fond of Oxtail soup and the commander, the well-known

Captain de la Taste, instructed the butler to buy half a dozen. Later he found half a dozen oxen tethered in a pen on the lower deck.

These royal cruises were splendid affairs with much pageantry as the ship called at ports along the way where triumphal arches of welcome would be specially erected

and military bands, guards of honour and local dignitaries of all races lined up for presentation. Think of Captain de la Taste at the summit of his career commanding

the most splendid of all the company's ships, commodore of the greatest privately-owned flotilla in the world with over 600 vessels, with royal guests on board whose

safe carriage was his sole responsibility.

Prince and Princess of Wales on the Japan, 1906

Captain de la Taste and his officers for the 1906 Royal Cruises

The Crown Prince of Siam travelled on the Siam in 1906 and the ship must have been renamed after him. Lord Mountbatten made his first visit to Burma in 1931 in the

company of the then Prince of Wales, who as Edward VIII was to abdicate in favour of Mrs Simpson. My old friend and mentor Alister McCrae, then a young manager with the

IFC, was one of the party on the Nepaul and was presented by the Prince with a silver cigarette case as a thank you for taking care of no doubt very smooth

arrangements. On that cruise flying boats belonging to the recently formed Irrawaddy Flotilla Airways met the ship along the way to delivery despatches and mail.

In 1895, John Innes, one of the company's directors from Glasgow, wrote:

Next to the style of our steamers was the superior type of our Captains... to this no doubt due to the almost complete immunity of accidents we experienced.

During my stay of nearly two months in Burma not a single accident took place, and this in the face of rivers with barely 6 to 12 inches spare water in places, and

torturous navigation which one requires to see in order to appreciate.

It is this tradition of good seamanship and safety that is perhaps the flotilla's greatest legacy in post war Burma. The European captains and their Lasacar crews

have long gone, yet their legacy lives on with commanders like Captain Maung Oo and the ability of such men to read the river, which seems almost supernatural.

Attempts to introduce GPS and waypoints failed, as the river channels change too fast for any survey boat to keep up. Echo or depth sounders do not work as when you

are coming downstream at 14 knots in debris-strewn, silt-laden water, the sands just shelf up or down: you will know you are aground before you can hear the ping. A

recent overfunded NGO proposed to spend millions installing fixed buoys to mark the channel between Pagan and Mandalay. Our

river masters just laughed when I showed them the video animation of the proposed scheme on YouTube. River channels alter daily; how on earth were they going to move all

these great lumps of concrete being used to tether the smart solar powered buoys?

Today, IWT run very few services as people travel in their cars and buses on the fast, new roads that run up and down the Irrawaddy valley. On the river, the only

movement is China-bound bulk freight on great barges and a few river cruise ships carrying tourists. When I signed a deal with IWT (as the nationalised IFC became in

1948) for the charter of a ship in 1996 they had a fleet of over 500 vessels, including a dozen built in Scotland just after the war that were still running until just a

couple of years ago. Tragically, most of that once great fleet has been abandoned and is turning to rust and rotting away. Young rivermen coming up will never know the

bustle and excitement of serving on a line ship, trading from port to port up and down the river. Curiously, we at Pandaw follow in the footsteps of the IFC, running the

exact same routes on the Irrawaddy, Chindwin and around the Delta that they did in the past. With commanders like Captain

Maung Maung Oo, the tradition lives on.