Back to Homepage / Blogs / Apr 2020

Katha and The Upper Irrawaddy

By Paul Strachan, Pandaw Founder

The only way to arrive at Katha is by water, which can take three days by express

steamer or a week on a Pandaw ship with frequent exciting village stops and walkabouts. Only by water does the whole romance of Burma and its magical river ports come alive.

And what a journey it is! Steaming up from Mandalay on our smaller K class Pandaw ships, we stop at the great unfinished pagoda of Mingun, with the world's second largest ringing bell and a ruined monument to the megalomania of past Burmese kings.

We continue through a maze of channels as the river scatters across the plain before narrowing at the Third Defile, where the river flows fast and deep through scrubby

hills. The sheer volume of water that pours down from Himalayan heights makes this an impressive sight. At the entrance to the Third Defile, there are the potteries

around Kyauk Myaung. A new bridge spans the Irrawaddy river here. During its

construction in the 2000s, one of our ships sailed under it and a couple of minutes later, an earthquake caused the central span to collapse into the river. In true

Burmese fashion, the crew simply beamed with delight, jubilantly declaring that luck was on our side. Our passengers then joined the relief effort, taking food and

blankets from the ship and delivering them to distressed villagers.

The Mingun Pahtodawgyi the biggest pile of bricks in the world

Mingun Bell

After several hours sailing up the Defile, we emerge into a further great plain, and again the river fragments. In the monsoon season, we chug along on a seemingly

infinite ocean of muddy blue waters, fighting the current and hardly going anywhere. I have seen bullock carts (which are hardly the speediest of transportation!)

overtake us as they wobble along the riverbank tracks. In the dry season, we bob through silver channels, and frequently become grounded. There is always a laugh in the

wheelhouse when we pass Pandaw Island where, on her maiden voyage in 2001, Pandaw

II spent a worrying five days grounded, but the passengers refused to be evacuated as they were having so much fun on board. No cruise would be complete without a

good grounding, which can last anything from a few minutes to a few hours. Our skippers usually manage to wriggle us free, but occasionally a passing tug must be

commandeered.

On the way to Katha we stop always at Kha Nyat, which retains its rural charm and is home to my late friend Saya U Tin Win with his fascinating private museum of local

artefacts unearthed during a lifetime of archaeological excavations in this area and Tagaung, in ancient times Burma's northern capital, with still traceable city walls and a splendid shrine to the nat Bo Gyi, who casts a protective eye

over passing ships — as long as he is buttered up with appropriate offerings. Another favourite stop is Hti-chaing, now a bustling port with roads leading into the

interior. A splendid hilltop pagoda offers a wonderful view up and down the vast sprawling river. In 1951, Norman Lewis overnighted at Hti-chaing on a heavily armed

steamer coming down from Bhamo. The town was in rebel hands, but in one of those very flexible Burmese arrangements, the government steamer was allowed to moor and trade.

On the east bank, the Shweli river joins the Irrawaddy. There are sinister looking Chinese mines in the hills that run along it, with new port facilities with enormous

barges alongside.

Between Khan Nyat and Hti-chaing are dolphin grounds, and sightings of these social creatures are frequent. Tragically, the Irrawaddy dolphin is now threatened by

'electric fishing', the most odious of practices where a long pole with an electric conductor on the end attached to big batteries is used to kill any form of marine life

within a certain radius. In the past, fishermen would thump an oar on the bottom of their boats and the dolphins would answer the call and help hoard fish into their

nets, but now they are threatened with extinction by the very fishermen they used to serve. Burma seems to have leapt from the 19th century to the 21st century, somehow

missing out the 20th century. Within a few months of very rapid change, people's needs and expectations changed too. Whereas a fisherman used to have little in the way of

outgoings, he now has to find money for a smartphone, a satellite TV and a thirsty outboard motor.

Until just a few years ago, nearly all the boats had lug sails (often a jolly patchwork of old longyis) or in the absence of a breeze, were pulled with oars. There

were the gorgeous hand-carved Irrawaddy boats with a throne for the helmsman high above the transom. Sadly, they are gone now, broken up for the value of their old teak.

In the 90s at Inywa, just below the Shweli confluence, we found what I think was the oldest village in Burma, with narrow, winding alleys and houses built close together

with great teak pillars and floorboards six inches thick, quite unlike usual Burmese villages of bamboo frames covered by rattan panelling. Inywa had the feeling of a

medieval village in central Europe. Most likely dating from the 18th century or even earlier, the houses had miraculously survived the twin perils of war and fire. We

went back a few years ago and they were all gone, again sold for their seasoned teak to buy smart phones and mopeds, being replaced by clap board and corrugated iron.

Likewise, the steamers have disappeared, replaced by buses that belt along new roads, turning journeys of a few days into a few hours. To replace the flotilla sunk in

1942, the newly independent Burmese government ordered a new fleet of shallow draft steamers from Yarrows of Glasgow in 1947. The then prime minister U Nu even visited

the Yarrow Shipbuilders yard in Govan to inspect progress (my grandfather George, a naval architect, worked there then and may have met him). Six stern wheelers were

sent out under their own steam from the Clyde, all boarded up for the ocean voyage. One of these was the original Pandaw ship that we refitted in 1998, and Sir Eric and

Lady Yarrow came out for the commissioning and maiden voyage. These were all running until just a couple of years ago, and I think our old Pandaw ship is the only one

still operational, now in the hands of a Chinese businessman. After seventy plus years, their redundancy was not due to any form of decay, but rather the fact that a road

infrastructure has replaced the river. People now bomb up the new highways on overnight buses, Burmese pop videos turned up to full volume, and fatal crashes are not

infrequent as manic drivers race against the clock. In the past, they would spend a few days relaxing on the decks chatting, eating endless snacks, and puffing on their

cheroots as the world sedately floated by.

U Nu at

Yarrows

Village near Katha

The river, once pulsating with shipping as vessels of every shape and size traded between ports, and every conceivable cargo was carried on the water, has now become

eerily quiet. There was nothing more fun than passing a P class line steamer packed to the gunnels with merry folk waving, whistling and calling as we passed. The upbound

vessel would often meet the downward one and they would swing alongside each other exchanging news, crew and rations. There would be a party atmosphere with high spirits,

and often friends were reunited as one jumped over to the other ship. Norman Lewis describes how in Bhamo in 1951, parties of people seeing off friends or relatives would

sometimes get caught up in the excitement and spontaneously jump aboard and decide to go with them!

Katha is and has always been an important trading post. In 1835 Inverness born Captain Simon Hannay was perhaps one of the first ever British visitors, travelling

upstream on an exploratory mission on one of the King of Burma's Italian-built steamers. He was amazed to find a selection of British-made goods on sale in the market,

long before Upper Burma was annexed by the British. I visited in the mid 1980s when Burma had banned exports and imports during its disastrous attempt at self-

sufficiency. Bhamo was a great smuggling hub with Chinese-made goods coming down river to be redistributed, so the markets were booming. Like all these Irrawaddy ports,

Katha remained prosperous through those hermit years thanks to its river trade.

I first visited Katha in 1985 and it was fortified then as a front-line position against the KIA (Kachin Independence Army). There were gun boats in the port and the

riverbanks were stacked with munitions. It was not unlike a scene from the film Apocalypse Now. Whilst the town remains in Burmese hands and is perfectly safe today, the

same KIA are not far away controlling the Kachin countryside just across the state border from Sagaing Division. The British foreign office therefore advises against

travel to Bhamo, the northernmost port on the Irrawaddy, which to this day is ringed by the KIA, a sort of Burmese version of Berlin during the Cold War, supplied by air

and armed convoys. Following my arrest as a foreign spy and subsequent release a couple of hours later, I was royally entertained by the local junta who told me that I

was the first foreigner to visit their town since the war. I am not sure that is quite true, but anywhere north of Mandalay had been off limits since the 1962 Revolution

and even before that as civil war and armed insurgencies raged through post war Burma of the 1950s. Norman Lewis was not allowed to dock in 1951.

Back then I had not realised that Katha was in fact the setting for George Orwell's Burmese Days, published in 1934. Given his scathing treatment of local society, his publishers insisted on changing all names and

places, and Katha became Kyauktada. The main features of the map included with the book were reversed so everything is in the wrong place. Whilst Burmese Days is probably

the most famous English language book written about Burma, it is in my opinion the book that tells you little about Burma and an awful lot about Orwell. Serving as a

colonial policeman, Orwell had been posted to Katha in 1926 where a simmering disgust at colonialism was later to form the basis of his Burmese Days. Everybody in the

book is unpleasant: Flory, the main character, is a depressing figure; his cronies at the club vile racists; the Burmese come across as corrupt and lethargic. The book

paints colonial life as mean, small minded and oppressive. All other books about Burma from this period (and the literature is considerable) present a vastly different

picture, with an emphasis that life was not like that in India, being less hierarchic and not at all snobbish. The picture they portray is one of open and friendly people

stationed in these remote outposts of the empire, who made any visitor or new face in town instantly feel at home. There was a mutual admiration between the British and

the Burmese, perhaps each admiring what the other was lacking. If anything, the British colonials were infected by the natural Burmese openness. When I first became

interested in Burma in the early 1980s, I joined something called the British Burma Society in London, which was then mainly made up with former colonials long retired to

England. How their eyes would light up and positively sparkle remembering old places and Burmese friends. They may have been retired to places like Tunbridge Wells, but

their hearts were still in Burma with the Burmese people. Despite many frustrations and difficulties, there is a real joy to living in Burma that comes from living

amongst and working with the Burmese - something we discovered in our thirty years of working there. I do not think George Orwell experienced that at all.

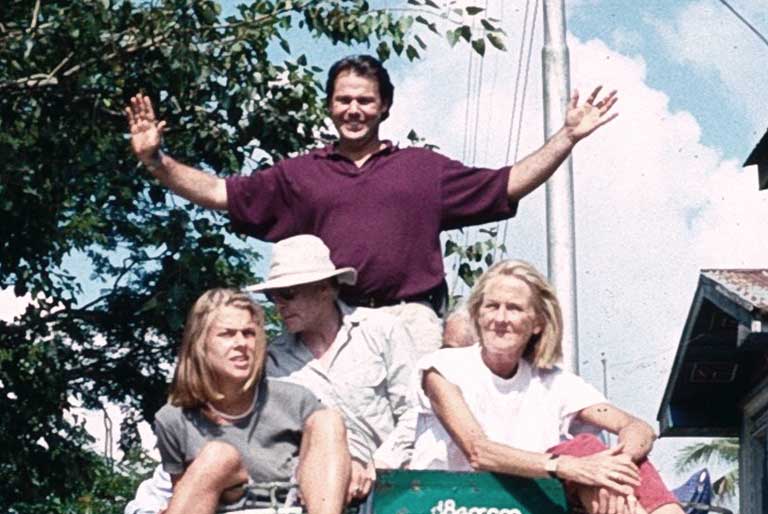

I made the same journey back up the Irrawaddy ten years later in 1995 with a bunch of fellow Burma buffs on a rickety hulk called the Irrawaddy Princess we had

chartered from a rich Chinaman in Rangoon. Burma was then 'opening up' and

the entire town turned out to welcome us. Even the streets leading to the strand road were packed, with people staring in amazed wonder at this bunch of strange

foreigners. Today the welcome is less effusive as they are now used to the sight of the occasional Pandaw vessel disgorging its cargo of camera-toting foreigners, but the

friendliness and sense of welcome is still there.

In the dry season, the ghats are steep and high, yet in the monsoon season you can moor up against the road and step out onto it. There is always a bustle of speed

boats coming in and out of the chaotic port taking people and their goods of to their villages. Looming above the ghats are a great blaze of golden spires – the town's

main pagoda straddling along the top of the riverbank. The town itself has not changed too much over the past thirty-five years that I have been visiting. Streets of

charming wooden shop houses, unchanged from the early 20th century lead up from the port. They are beginning to be replaced by ugly buildings covered in bathroom tiles

with mirror glass windows, owned by Chinese businessmen intent on hoovering up local real estate. But at the time of writing, the old Katha houses are still in the

majority. The shopping streets lead from the port to the heart of the old town. This was once the racecourse, which jockeys used to career around, but it is now a sports

ground with a running track. Horse racing was banned by General Ne Win during his Puritanisation of Burma in the 1960s, and the grounds were then used for the pageantry

of the Burma Socialist Programme Party with lots of parades and waving of coloured flags.

The Race Course, Katha

Katha Main Street in the 90s

To the south lies St Paul's catholic church, a pretty wooden structure with a belfry, and the jail, both unchanged from Orwell's day. To the north of the old

racecourse, the Civil Lines remains more or less as it would have one hundred years ago. There are great dak bungalows with galleries of verandas running all around at

all levels. Some like the District Commissioner's are vast, designed for entertaining on a grand scale. Here on the Civil Lines, Orwell would have had his house. Some

guides will direct you to the home of the current police chief on the assumption that Orwell, as Police Superintendent, would have also have lived there.

Catholic Church, Katha

Dak

Bungalow, Katha

After much hunting over many a visit to Katha, I finally found the 'club' following a sign in Burmese for the Tennis Club. It is a nondescript and rather sad structure

on a bank overlooking the flood plain. Now a local government archive, it had been a Burma Socialist Programme Party office after the 1962 revolution. If you go in, you

can see the hatch through which Indian bearers would pass the chota pegs from a servery. It is not very impressive, a low-key drinking den with a token tennis court out

front. No wonder that after the introduction of dyarchy in 1923 and the handing over of government to an elected Burmese administration that led to the admission of

Burmese to the clubs, few Burmese could face it.

The

Club, Katha

Old IFC ships

A must when visiting Katha is a stop at the fire station to see the fire bells. Only they are not fire bells - they are ship's bells taken from Irrawaddy Flotilla

Company Steamers sunk here at Katha in 1942. The bells of the Japan (1905) and her sister Siam Class ships came off the greatest steamers the IFC ever built. Each was 326

foot long (exactly the height of the Shwedagon Pagoda) and 76 foot across the sponsons, licenced to carry 3000 passengers and making speeds of 14 knots upstream – about

double what we do. These enormous paddle steamers towed a flat (or barge) on either side so would form a combined span of 150 foot across the river. Surely a sight to

behold.

Japan 1905 Ship's Bell

Siam 1904 at Mandalay

With the Imperial Japanese Army hot on their heels, the British evacuated Rangoon, adopting a scorched earth policy of denying the enemy most infrastructure as they

retreated. Ports, oil refineries, rice mills, bridges and over six hundred ships of the Irrawaddy Flotilla were denied. In the low waters of February, Katha was as far as

these deeper draft vessels could reach, and were sunk here by their own officers holing the thin hulls with Bren guns and detonating gun cotton explosives. Broken-

hearted, the company's officers got in cars and set off for India until the fuel ran out, then simply walked there over a couple of mountain ranges to sign up with the

14th army that would victoriously return to Burma in 1945.

Clearly an enterprising fire chief managed to save the bells, and some years ago I cheekily made an offer for them without success. Norman Lewis describes great

jungle-covered hulks sticking out of the river when he passed here in 1951, but by the 1980s when I first visited Katha they had long rotted away. Then in the mid 90s,

when Burma seemed to be waking up after thirty years of self-imposed isolation and the country was abuzz with enterprise and industry, entrepreneurs started salvaging the

hulls. The great sand island that had lain off Katha had in fact been a graveyard of ships — dozens of them. Using enormous pumps, the sand was shifted, and these hulls

were laid bare. There were the Japan, Siam and Taiping. I can proudly say that I have walked their decks. Divers attached to what looked like garden hoses swam deep into

the holds bringing up all manner of artefacts – I purchased from them various bits of cutlery and crockery embossed with the company livery and at long last a ship's bell

of my own. I souvenired four Bren gun cartridge cases on the decks and even pocketed a rivet or two. My best find was an actual cardboard ticket, found in the ship's

safe in the purser's office that somehow had survived fifty years under water. I showed it to an old Burmese friend who instantly remembered these tickets with the names

of the stops printed along the sides, in Burmese on one side and English on the other — they would be clipped by the name of the port you had bought your ticket for. The

great 326-foot long Siam Class ships had all broken their backs so would never sail again, but the crafty salvagers cut them in two and welded on new bows or sterns.

These great ships sail again!

Ticket English Side and Burmese Side

Katha Bathers

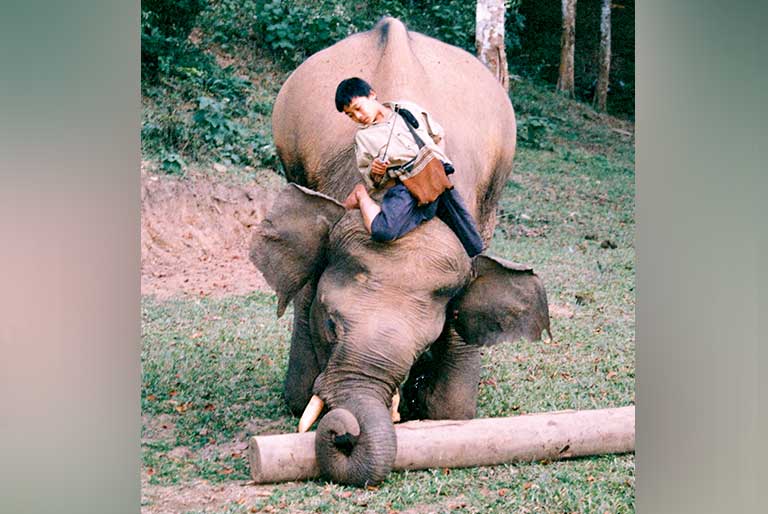

Perhaps one of the most enjoyable events on any visit to Katha over the years was a trip into the jungle to visit an elephant camp. This was never something we

guaranteed as sometimes the elephant camp could not be found, even after driving around on bumpy rutted jungle tracks for hours, usually with our guests swaying in the

back of an old lorry or pickup truck. After all, working elephant camps do tend move around depending on where the work is. If found, it was important to get the time

right as elephants have very strict working times and very precise body clocks. They do not take kindly to be pulled away from their afternoon foraging break, or having

their evening bath delayed by the arrival of a bunch of camera-clicking tourists. If we got it right then it was a thrill to see the elephants stacking logs in perfect

order and working in harmony with their oozi or mahout, some just teenage boys riding an elephant of the same age that they will have grown up with.

Elephant

Camp

Paul on the Roof

Rack Looking for Elephants

One of Burma's best stories during the thirty-year isolation was the continued good management and conservation of the forests. Using a German system adopted by the

British, mature trees were selectively felled and extracted using elephants, causing minimum disruption. For every tree felled, several saplings were planted and thus

there was a policy of renewable forestry that had existed for over a hundred years. Then came the sanctions called for by Aung San Suu Kyi and responsible for so much of

what went wrong with Burma: the Chinese exploitation of all resources, including human resources, coupled with the West's twenty-year denial of basic humanitarian aid.

The heavily sanctioned military junta were unable to trade with the wider world and ceded vast tracks of forest to cronies. In went the big machines, clear felling vast

tracks and resulting in environmental devastation. For twenty years we saw log raft after log raft go down that river — it was hard to believe there were so many trees in

Burma. Today there are very few rafts of teak; we pass the odd cargo of jungle wood stacked on a barge; gone are the great one-acre rafts with whole villages camped out

on them in pretty little huts. The teak money went to the Russians for T54 tanks and MIG 29 fighters and to the Chinese for gunboats.

Back to the elephants; with all this, they were out of job and their handlers came up with the idea of setting up an elephant camp for tourists — mainly domestic

tourists but aimed also at foreign tourists — not that Katha gets many. How tragic it is to see these splendid beasts who had taken pride in a useful day's work, being

put through their paces to do tricks for tourists. It is a difficult question for us as we are pressured by animal rights groups to not support these elephant camps, but

if we do not, how will both the animals and their handlers eat?

Katha also boasts a golf course which unsurprisingly for Burma is situated within the army cantonment area in the lush and lovely countryside inland. There is no issue

with going in and the club secretary is happy to take your green fees. They seem to add a new hole each year, and last visit were up to fourteen. Rather oddly some holes

cross each other and on one occasion my son Toni, who is ethnically Burmese, strolled across like the scruffy teenager that he was dressed in flip flops and ragged T-

shirt, looking lost. A Burmese group playing the other way stood astonished, then a very angry man started roaring with rage. I was informed

by my caddy that this was the military commandant of the Katha region and he was going to have Toni shot. We played on and then after the game in the clubhouse the

colonel, as he was, proved very charming and apologised, having not realised that Toni was actually with us, and we all had drinks together. Learning that I was in the

travel trade, the colonel was keen to promote Katha as a golf tourism destination and I obligingly promised to spread the word, which I am doing now.

Despite such forays into tourism, I am glad to say that Katha has really changed very little over the thirty something years I have been going there. People are far

freer and more relaxed than they were under Socialism, if less innocent and exuberantly generous, and far more prosperous with everyone buzzing about on mopeds and

scooters as they go about their business. The friendliness is still there, as are all the pretty wooden shop houses and the colonial dak-bungalows, that extraordinarily

linger on despite their hundred plus years and perishable materials. Like its architecture, Katha would seem at first glance to be eminently perishable too, but likewise

lingers on, having changed little over the three decades I have been visiting.

Further Reading

Norman Lewis Golden Land, London 1951

George Orwell Burmese Days, New York 1934

Paul Strachan, Mandalay: Travels from the Golden City. Gartmore, 1994