Back to Homepage / Blogs / Apr 2018

By the Old Moulmein Pagoda

By Paul Strachan, Pandaw Founder

BY THE old Moulmein Pagoda, lookin' lazy at the sea,

There's a Burma girl a-settin', and I know she thinks o' me;

For the wind is in the palm-trees, and the temple-bells they say:

"Come you back, you British soldier; come you back to Mandalay!"

Come you back to Mandalay,

Where the old Flotilla lay:

Can't you 'ear their paddles chunkin' from Rangoon to Mandalay?

On the road to Mandalay,

Where the flyin'-fishes play,

An' the dawn comes up like thunder outer China 'crost the Bay!

Kipling only spent a day in Moulmein

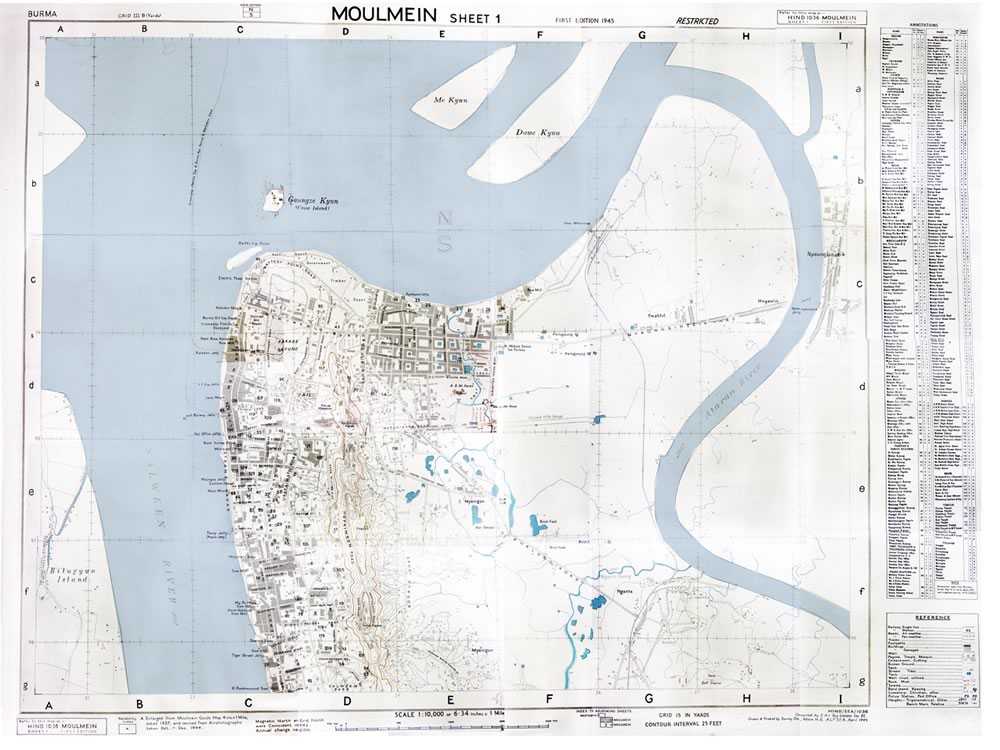

where he disembarked for a day's tour on his way to Japan in 1889. Of course, the poem makes geographical nonsense, as Moulmein is nowhere

near the Irrawaddy River and the paddles chunking to Mandalay, which he never visited. Moulmein sits on the estuaries of three rivers: the Salween, the Gyaing and the Ataran that spread out like a great map when viewed from the Kyaik-tun hilltop pagoda.

Kipling later wrote that that day he fell in love with a Burmese maiden whilst visiting the town's main pagoda. "Only the fact of the

steamer departing at noon prevented me from staying at Moulmein forever...". We have to thank this nameless belle who was an inspiration for

one of the greatest poems in the English language. Ironically, the words 'Kipling' and 'Burma' became synonymous yet he knew the country little, jumping off the steamer for a quick sightseeing in Rangoon and Moulmein. Despite the brevity of his visit, no European ever captured the magical essence of Burma better than Kipling, whether in the 1890s or today.

Moulmein was a British creation following the First Anglo-Burmese War of 1824 when the territories of Tenasserim and the Arakan were ceded

to the British. The choice was strategic, as opposite was the Burmese town of Martaban, which had been an important provincial capital for

centuries, sitting at the mouth of the great Salween, the longest river in Burma. Strategically with rivers on two sides, the northern point

opposite Martaban was called Battery Point, with its guns pointing across the river at Burmese territory.

The East India Company absorbed this new territory with some degree of reluctance, as it would be costly to garrison and administer with

little potential for profit. Colonel Bogle, the first Civil Commissioner (equivalent to a governor), built himself a palatial mansion called

Salween House set in a spacious park on one of the hills. Later this was considered too grand for a civil servant's residence and it was

turned into the court house and town offices. The Board of Directors in Calcutta were soon proved wrong and Moulmein developed into an

important economic hub: initially teak extraction, then obviously ship building taking advantage of abundant timber; later, rubber planting

and tin mining.

John Crawfurd, a native of Islay who had been an army doctor and former 'resident' at the Court of Ava and Dr Wallick, the superintendent

of the Botanical Gardens in Calcutta, travelled on the Diana, the first steam paddler in Burma that had been brought over from Bengal in 1824

for the Anglo-Burmese War. Despatched to Moulmein she made an expedition up the Ataran River with Crawfurd and Wallick to inspect the forests

and logistics of its shipping. What they found surpassed all expectation. Even after power shifted to Rangoon, Moulmein remained a teak town,

shipping by the 1910s 60,000 tons of teak a year, about one fifth of the country's total production.

William Darwood, the Diana's chief engineer, realising the possibilities, stayed on in Moulmein where he married the daughter of the ship

owner Captain Snowball, who had also just settled there. Snowball was famous in all the Indian Ocean ports and it was significant that he

chose to settle in Moulmein. In 1825 this was the place to be. An Englishman, Darwood had served in the Bengal Marine and lost a leg in the

Diana's assault on Martaban in 1824 for which he had been awarded a pension. He set up as shipbuilder and between 1833 and 1841 launched

eleven vessels. Darwood was one of over twenty ship builders established in Moulmein by the 1840s. As wooden hulls gave way to steel ones by

the 1850s, ship building declined in Moulmein and after the Second Anglo-Burmese War larger vessels were to be built on the Rangoon River at

Dalla. The river banks still abound with boat builders constructing trawlers and river launches.

Many of Moulmein merchants were Scots. TD Findlay came to Moulmein in 1840 by way of Penang where he was to be a partner in a family owned

store. He passed on that opportunity preferring to set up shop in Moulmein, where on a visit he realised the potential and formed a

partnership with James Todd. Todd Findlay & Co imported goods from Glasgow and sent back teak in the same ships. Everything was in the hands

of a small interrelated group of Glasgow families: the factories that produced all necessities for life and trade in the tropics; the ships

that transported the goods; the shops that sold the goods; the insurers who covered the risky sea voyages; the logging companies; and, the

banks that financed it all. Findlay and his network encapsulated this model. Later, with the shift to Rangoon, Todd Findlay & Co would become

the main investors in another great Scot's project: the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company.

Moulmein was important for only thirty years, as after the Second Anglo-Burmese War Rangoon became the capital of all Lower Burma.

Thereafter Moulmein became a somewhat sleepy provincial town, of economic rather than political importance. Most of the great Scots'

commercial houses relocated to Rangoon, leaving branch offices in Moulmein. Gone too were the governor and the military garrison. Moulmein was

regarded as a very pleasant and comfortable town and a place of retirement for Europeans who chose not to go 'home'. This was the Bournemouth

of Burma with quiet shady streets, dak bungalows and huge gardens strung along the three roads of the British town.

Climbing the Kyaik-tha-lun pagoda hill to stand where Kipling stood, mistaking the Salween for Irrawaddy and becoming besotted, you can see

the original town laid out between the corniche and the small range of hills which the pagoda dominates. It originally consisted of three

thoroughfares, the Strand, Main Road and Upper Road, running parallel to the river along which the merchant's godowns and counting houses sat

looking out across the Strand at their ships at anchor. You can see now that the town has spread inland to the eastern side of the hills.

Ranged along the town hills are diverse pagodas and monasteries, nearly all dating from colonial times and in a hotchpotch of colonial

classical and Rococo Burmese styles. The largest and most splendid Hindu temple in Burma sits brilliantly amongst this architectural melee.

Gazing across the town you will see that all religions are represented and I would hazard that, there are as many mosques as pagodas, for

under the British this was very much an Indian town. Not to be outdone by mosque or pagoda, church towers and steeples soar skywards in a mix

of Gothic and Romanesque. Just beneath on the west side you will see a huge prison radiating out from a main block like a fan. Moulmein Jail,

once a model prison, memorialises the legacy of the British as much as the churches and godowns. For the British were to pacify a territory

where dacoits terrorised villages and pirates prayed on coastal traders. (Looking through my zoom lens I could see a very active prison

population playing football or chinlon, cheered on by the guards.) To the north the great Salween graciously curves its way on the journey to

distant Tibetan peaks. Closer you will see the jagged Zwekabin range of hills, the most prominent of which was known as the Duke of York's

nose, though which Duke of York remains a mystery. From the east the Salween is joined by the Ataran and Gyaing Rivers that brought rafted

teak down from the great forests that abutted Siam. Three enormous rivers thus meet in the estuary between Moulmein and Martaban and it is no

surprise that Moulmein was to become an important port and trading post.

Moulmein was once home to a young colonial policeman called Eric Blair, who later adopted the pseudonym George Orwell. His essay 'The

Shooting of an Elephant' was set in Moulmein and begins with the wonderful line: "In Moulmein, in Lower Burma, I was hated by large numbers of

people — the only time in my life that I have been important enough for this to happen to me."

Orwell had strong Moulmein connections as his mother's family, the Limouzins, were from here. A Frenchman, his great-grandfather was a

shipbuilder from Bordeaux and founded Limouzin & Co in 1826. Orwell arrived exactly one hundered years later and in the previous year his

grandmother had died in Moulmein. There is still a Limouzin Street in downtown Moulmein.

In 'The Shooting of the Elephant', Orwell shows an early disillusionment with the colonial system of which he, as the town's police

superintendent, was a pillar. He describes how he was pressured by a crowd into shooting an elephant in musk even though it had ceased

rampaging and was no longer a danger. Somehow the prestige of the British required him to act in an unnecessary and cruel way causing immense

suffering to the beast as it died a long slow death. The shooting was a symbol of colonial rule. In Burmese Days, which is set up on the

river in Katha, Orwell went on to ridicule the tedium of provincial colonial life. His record of life in Burma was deeply cynical, somewhat at

variance with nearly all other contemporary accounts from this time.

The fact that the poor elephant was a Moulmein elephant is relevant, for Moulmein was 'elephant city'. Teak rafts were floated down the

three rivers to be gathered at their mouths and brought ashore by elephants, the logs were transported by elephants, even stacked in neat

piles by elephants. Working elephants were everywhere in Moulmein and a feature of daily life. I wish there were statistics on this but there

must have been several thousands stabled here. Elephants have identical life spans to humans, so most beasts were good for forty years of

service. They were thus very valuable items. I once met a member of the Wallace family of Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation who returned to

Burma in the nineties and encountered elephants branded BBTC before the war still working away.

I first visited Moulmein in 1986. I was going to visit Professor Hla Pe who had been emeritus professor of Burmese at London University,

before my time there, and had retired to Moulmein. I had heard many stories of Saya Hla Pe's charm, wit and eloquence and had longed to meet

him. Back then under the Ne Win dictatorship foreigners were only allowed to travel to the usual tourist spots and I had to get special

permission to go down to Moulmein. As the roads were so bad the train was the best way to get there. The terminus was at Martaban from where a

ferry took me across the mile-wide Salween to Moulmein.

As I crossed from the railway platform to the jetty I was confronted by a beaming police officer, "you are going to visit Saya U Hla Pe",

it was a statement rather than a question, for the only foreigners ever to arrive in Moulmein were Saya's guests. The police were very kind

and insisted on taking me across the river in a police launch and on the other side a police jeep was waiting to take me to Saya's

mansion.

This was the first of several visits to Saya over the years and the professor was one of the most erudite man in Burma and a fount of

information on Burmese literature, language and culture. After a dram or two, he would hint that life in a provincial town, the Burmese

Bournemouth, could at times be dullish and thus he was all the more delighted to receive guests. His wife was from Moulmein and had insisted

that they live there after his retirement from London University. Back then an index-linked UK pension went quite a long way in Burma and Saya

lived in fine style and was something of a local celebrity receiving the obeisance of the town's great and good. On one occasion, not long

married to Roser, we were sitting having dinner and the lights went out. Saya rushed to the phone and I heard him berate the manager of the

local power station "didn't you hear that I have VIP foreign visitors staying".

Saya is no longer with us, and Moulmein, as with so many Burmese towns, has seen some change. When we returned in the early 90s, after the

SLORC putsch and a scramble to develop the country that collapsed into sanctions and the clasp of the Chinese, the old wooden godowns and

counting houses were being demolished along the Strand in favour of the most architecturally miserable apartment blocks imaginable. Yet there

are still many architectural gems to be found in the residential areas.

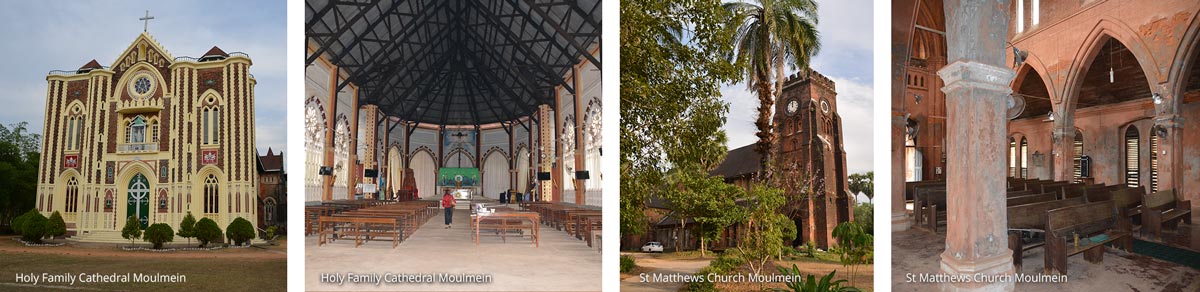

It is best to start with the churches. My favourite is St Mathews, which is C of E, and so quintessentially English that for a moment you

might think you have been transported back to the Home Counties. Consecrated in 1890 by Bishop John Miller Strachan (my adopted ancestor!) who

was the first bishop of Rangoon, it was designed by the fashionable London firm of St Aubin and Wadling, and said to be identical to the

English church in Dresden. The construction was funded by a single donor AW Kenny of whom I wish we knew more. The tower was added by the

Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation, in memory of their young men who lost their lives in the Frist World War. Nearly all the memorials that

would have covered the walls were desecrated by the occupying Japanese forces in the Second World War, except for one plaque remembering those

of Moulmein who fell in the First World War. Burma buffs will recognise one or two old Burma names there including two Foucar boys, their

family firm of Foucar & Company being a leading timber merchant. Moulmein and its colonial families go back further than anywhere else in

Burma except perhaps Akyab in the Arakan. People like the Foucars stayed on and on, they may have sent their children back to be educated in

England at absurdly early ages, but those kids came back, generation upon generation. ECV Foucar, a Rangoon lawyer and the fourth generation

of his family in Burma, was author of I lived in Burma which is one of the best anecdotal descriptions of colonial life between the 20s and

40s – far more real in my opinion than Orwell's diatribes.

St Mathews dedication stone remains outside and you will see that the stone was laid by Sir Charles Crosthwaite, Chief Commissioner for

Burma and author of The Pacification of Burma, a classic work on insurgency that the Americans ought to have read before heading into

Afghanistan. The choir stalls and ceiling bosses are said to be made from English oak and if you climb the belfry you will see the bell, cast

in the foundry at Madras. There was a complex clock mechanism, with four clock panels working of one mechanism. It was explained that the one

man in Moulmein who knew how it worked, and could repair it, had died and alas the clock died with him.

The church had been used by the Japanese to store salt during the war and the salt has caused erosion into the brick work. One Pandaw

passenger in the 90s was kind enough to donate a considerable sum towards the churches restoration. Some pointing work has been done but there

is still much to do. When I was last there the priest showed me a collection of Christian headstones he had rescued when SLORC appropriated

the Christian cemetery for redevelopment. I did not see them this time and wonder what happened to them?

The Roman Catholic Cathedral, with its broad nave and lack of aisles, is more French in feel and was reroofed following war damage. The

presbytery adjacent is a fine brick colonial house and typical of nearly all the colonial residences of Moulmein, with its shaded loggias

running around and crisscross leaded fenestration. I love the anchored crosses found on the doors, something I have only seen on the churches

of Burma emphasising a strong nautical element within colonial Christianity. An elderly nun showed us the tombs of French priests, set within

the north transept including Pere Chirac, MEP (Mission Etrangers de Paris).

Across the road is the American Baptist Church. This was the first church in Moulmein and its first incumbent was the Adoniram Judson

(1788-1850) of Middlesex, Massachusetts, who had been in Burma since 1813. An indefatigable character, he travelled throughout Burma with

personal bibles in English, Latin and Hebrew. Judson was the first person to translate the entire scriptures into Burmese. Still to this day

his bible is used in most Burmese Christian churches, whatever their denomination. He is the King James of Burma. Judson also produced the

first Burmese-English dictionary, a well-thumbed copy of which sits on my desk as I write. His success amongst the Burmese was minimal, but

amongst the animistic Karen in the jungles of Tenasserim, just up river from Moulmein, Judson was viewed as a messianic figure. His legacy is

huge: not just in Burma, where there are Judson Memorial churches everywhere, but right across in America there are Judson colleges,

universities and libraries; there is even a town called Judsonia in Arkansas. In fact, far away in torpid Moulmein Judson theologically

defined the American Baptist Church, some would say invented it, and his legacy lives on not just in Karen villages but in the counties of

Texas.

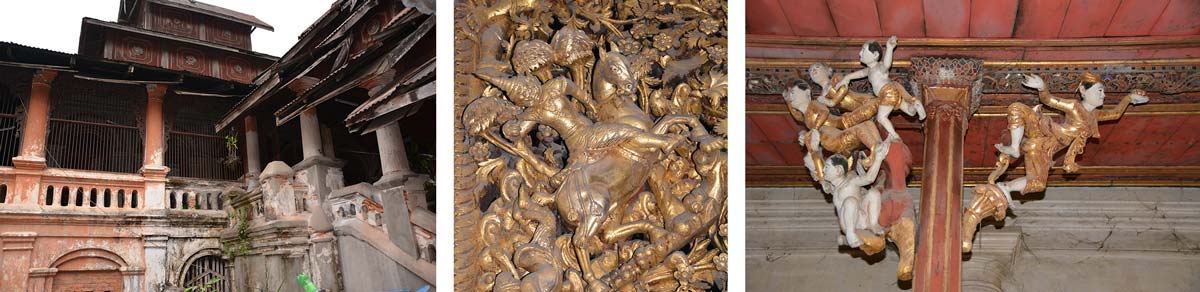

Of the religious edifices in Moulmein, whether cathedral, masjid or joss house, my favourite remains the Buddhist monastery of Sein Don

Mipaya, situated on the town hills just to the south of the Kyaik-tha-lun pagoda and connected to its south stairway. Sein Don had been one of

King Mindon's queens who fled to British territory following the palace coup of Thibaw in 1859 and the subsequent cull of rival claimants.

Given a house and pension, she lived with her court in some style in a Moulmein suburban house and decided, as her act of merit, to build this

most sumptuous of monasteries. Despite its appalling condition, it remains one of the finest in Burma. The queen summonsed artists and

craftsmen from across Burma to work and you can see they were the crème de la crème when it came to wood carving. The bracket figures

supporting the column capitals are dynamically carved and full of vigour. The figures carved on the doors are full of wit and humour. When I

last visited in the early 90s, the monk showed me the gaps where figures had been stolen in a nocturnal break in. At that time, when Burma was

so poor, there was much thieving from religious sanctuaries, the loot going onto the international art market. Today Moulmein is a rich town

once again and you can see that wealth being showered in ambitious new shrines throughout Mon State, it is a shame some of that money does not

go into restoration.

It is well worth pottering around the monasteries dotted along the town hills. There are several fine examples of colonial Burmese

religious buildings and do not miss the monumental bamboo image. You can see that it was not just the dour scottish merchants who prospered

during these times. These splendid monasteries, prayer halls and shrines are the work of merit of a very prosperous Buddhist community,

whether Mon or Burmese.

Along the Strand, despite the depredations of SLORC military planners in the 90s, there is still a good feel. There is a lively night

bazaar where you can gorge yourself on barbequed sea food and a couple of very good restaurants. Moulmein today is the cleanest city in modern

Myanmar and I was amazed to see plastic recycling stations. It would seem the Mon are far more house proud than their neighbouring Bama. There

is a good museum of Mon culture that is worth a visit too. It is great to see the Mon going around in their traditional costumes with very

jolly coloured checked taipon jackets. Moulmein is visibly prosperous today, same as it was two hundred years ago, as it sits astride the

three rivers and commands all trade and the sea. The estuarial port is too shallow for modern shipping, but today the connections go the other

way with the Pan Asian Highway passing through and connecting Moulmein to Thailand and beyond.

Over the river to the west of Moulmein is Bilu Kyun or Devil Island which is now connected by a bridge. Guide books will tell you of

artisanal villages: there is one that specialises in making slate tablets for schools and another for smoker's pipes. We visited the pipe

village and bought quite a nice pipe for Roser's brother. The shop keeper explained that before trade for pipes had been good but nowadays few

people smoke, so the wood carvers had branched out into other heavily carved products, more suited to the local market. I am not sure I will

be hurrying back to Bilu Kyun.

An essential excursion out of Moulmein is to Than-byu-zayat, about one hour south of Moulmein. Situated close the 'Death Railway' built by

the Japanese in the Second World War, where they brutally expended prisoner of war labour, not to mention local slave labour. Here the

Commonwealth War Graves Commission maintains the war cemetery as immaculately as if it were in the English counties. A visit is deeply moving

and it would be a hard-hearted sort of person not to feel the tug of tears coming on. Look at their ages: many the same as my own son at 21.

Alongside British servicemen are laid to rest young Australians, Dutchmen, Gurkhas and Indian. The Muslims point to Mecca and Christians to

the East. Their sacrifice was huge and their name really does live forever more.

We went down to Amherst Point, now called Kyaik-ka-me, partly in the hope of finding some good beaches and party to look at possible

mooring positions and road access points for the Andaman Explorer when she moors here next year as part of her Burma Coastal Voyage. There

were no nice beaches (they are further south) and the pagoda complex on the point tacky and of little interest. Along the way, you will see

endless rubber plantations and judging by the number of trucks we saw bearing mats of raw rubber, the industry must be booming. More fun is a

stop at the Wan-sein-toya complex on the road back from Than-byu-zayat. Here you will find the largest reclining Buddha in the world that the

fit can climb up through a system of internal staircases. This was the work of the late Wan-sein-toya Sayadaw whose tomb you can visit close

to the car park. He is enshrined within a very symbolic gilded sampan. I just wish he had channelled some of those generous donations into

restoring some of Moulmein's Buddhist heritage.

From Moulmein you can travel easily to Hpa-An, capital of Karen State, by car in a couple of hours but better a day trip by boat up the

Salween. The Salween is very lovely with the Zwekabin mountain range running alongside and at times you would think you were in Guelin in

China, so wonderfully mystical is the karst landscape around. Hpa-An is now another lively, prosperous Burmese city and a centre of education

with several universities and colleges. The Karens here are predominantly Buddhist, having not succumbed to Judson's appeal. Worth a stop is

the Mahar-sadan cave. You can walk through several great Buddha-filled caverns (carry your shoes as you will need them later) and you pop out

of the other side to be rowed back round the mountain across a lake, through further grottos and then along a mini canal which the industrious

Karen had dug out all in the name of local tourism, which they seem to benefit from.

Moulmein was only for twenty-seven years under the British when it was of political importance, but its legacy remains strong, whether with

its literary connections or architectural remnants. It is now the heart of a resurgent Mon regionalism, where after fifty years of Myanmar

suppression the Mons can emerge again proud of their identity, language and culture. The Mons were the first of the South-East Asian peoples

to be enriched by Buddhism producing moving sculpture and an enduring interpretation of Buddhist texts. It was thanks to the Mon-Khmer that we

have the temples of Angkor Wat; and in 11th century Pagan the captions on the mural paintings are in Mon, not Burmese. It was through the Mon

that Buddhist literature, art and iconography disseminated through the region. The town at the confluence of the three rivers may not be very

ancient, or may not have been important for very long, but it represents today a long, rich and deep culture.

Further Reading

GW Bird, Wanderings in Burma. Bournemouth 1897.

RR Langham-Carter, Old Moulmein. Moulmein, 1947.

Emma Larkin, Finding George Orwell in Burma. New York, 2005.

Alister McCrae, Scots in Burma. Edinburgh 1990.

The MY Andaman Explorer will call at Moulmein on her ten night Burma Coastal Voyage from Rangoon to Kawthaung via Mergui and its archipelago.