Back to Homepage / Blogs / Aug 2020

The Flotilla at War

By Paul Strachan, Pandaw Founder

The Irrawaddy Flotilla may be remembered for opening up a great and rich country to trade and travel, and a prosperity it had never known before or since, but it is not always remembered that it was born out of war and met its fatal demise in war. Whilst never a government monopoly, and most certainly never part of a ship owner's cartel, the flotilla always enjoyed a semi-official status with the colonial government in Rangoon, carrying the proconsuls of empire and perhaps more profitably benefiting from mail contracts that subvented services on less profitable routings, not unlike the mail steamers on the Scottish west coast routes. It very much suited Rangoon to have so great a strategic resource that could at a moment's notice be deployed for military purposes. In fact, the flotilla was formally deployed in four wars, and it could be argued that the flotilla had its roots in the First Anglo Burmese War of 1824. Post- independence, ships of the new flotilla, under the the Inland Water Transport Board, that succeeded the nationalised Irrawaddy Flotilla Company, continued in a martial role in the civil wars that have ravaged the land since. To tell the story of these flotilla wars is to tell the story of Burma, of why and how it was colonised, lost in the war, won back and then abandoned to internal conflicts that continue to this day.

1st Anglo Burmese War

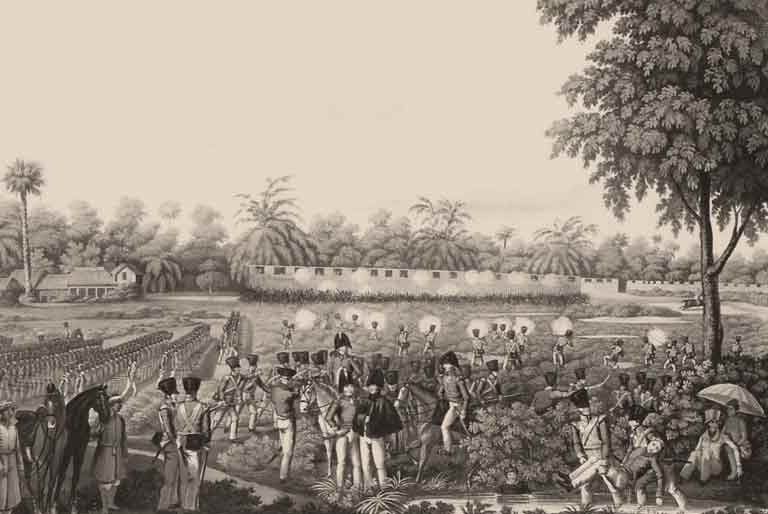

The Diana in Rangoon, 1824

The paddle steamer Diana had crossed over the Bay of Bengal with a task force of sixty-three ships carrying 8,500 British and Indian troops under the command of Sir Archibald Campbell at the outset of the First Anglo Burmese War in 1824. The Diana was in fact the first steam ship ever to be deployed by the British in battle as up till then, steamers were mainly used as tugs to tow sailing ships in and out of port. It would be decades before the Admiralty woke up to the advantages of having vessels that were not dependent on the vagaries of the wind. Fitted out with Congreve rockets and commanded by thirty-two-year-old Frederick Marryat, later to become a successful novelist, the Diana's funnel was as high as its mast, with "the very sight of her causing more consternation than a herd of war elephants". The Diana led the attack and occupation of Rangoon was one of the few moments of glory in what was otherwise described as "the worst managed war in British history".

The invasion of Burma by sea, rather than the more dangerous overland route across Assam, was the culmination of thirty years of clashes along the border between the territories of the East India Company and the Kingdom of Ava. Since the rise of the Konbaung kings in the 1750s, Burma had embarked on an imperial journey that not only matched the glory of the Pagan empire that had dazzled the world five hundred years before, but surpassed it in territorial gains. Conquering first the Mon kingdom of Pegu and then absorbing much of Siam, in 1785 King Bodawhpaya took the Arakan, leading to a mass exodus of Arakan refugees into British Bengal. Further clashes occurred in Assam, Manipur and other East Indian states claimed by the Burmese, but under Calcutta's sphere of influence. The final straw for the British was the Burmese occupation of the island of Shapuri and an ultimatum by Lord Amherst, the Governor General, to King Bagyidaw for the troop's removal, which was taken by the Burmese as a sign of weakness, leading to the kidnap of two British naval officers. Amherst's attempts to avert war with a boundary commission also foundered on Burmese imperial haughtiness and war became inevitable. Wars were expensive and at this point the British had no designs on acquiring great swathes of additional territory that would prove costly to garrison and administer. The idea was to make a show of force and secure borders. Amherst did not reckon on the fighting abilities of the Burmese and the tenacity of their general Mahabandula, a brilliant strategist who had been waiting for the British in the Arakan and managed to turn his army round and march them over the generally impassable Arakan Yoma to counterattack in Rangoon. He fell back to Donabyu and Campbell moved his force across the delta to confront Mahabandula there. Hit by a rocket, Mahabandula died and with the loss of his charismatic leadership, the Burmese army fell into disarray and withdrew.

By the Treaty of Yandabo of 1826, Ava ceded the coastal provinces of Tennasserim and Arakan. Despite the victory, this was a wasteful war and of the 40,000 troops deployed 15,000 died and of the 3,586 troops who landed at Rangoon, 3,115 died of disease and only 150 made it into battle. By the treaty of Yandabo the East India Company now had possession of two provinces that at first sight would cost more to administer than could be collected in revenue. And as for the Diana, she crossed over to Moulmein and was used for exploration of the Salween and Ataran river systems where eventually the British were to profit from the great teak forests, tin mining and rubber tapping here in Burma's deep south. The Arakan was to prove agriculturally rich, feeding Indian markets and producing a wealthy, educated Arakanese land owning class.

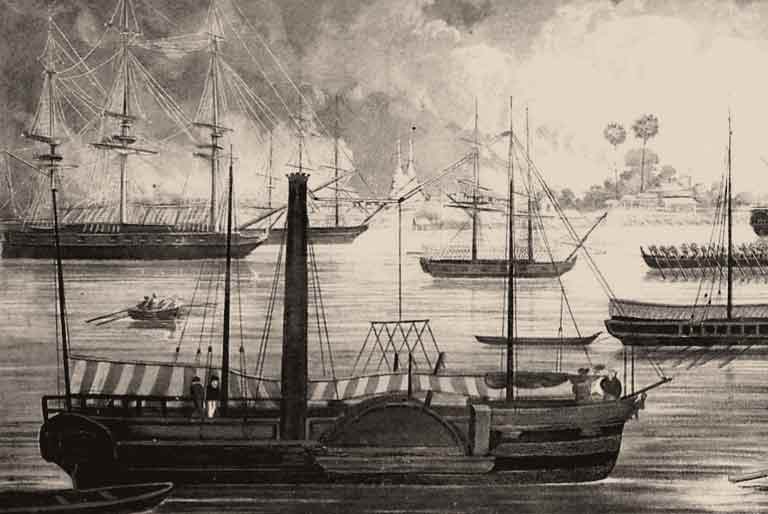

The Irrawaddy Flotilla proper was created for the Second Anglo Burmese War of 1852. This war like its predecessor was the product of misunderstandings. The Burmese in their ignorance had not realised the power and might of the British Raj. The British were equally ignorant in their failing to understand the complexities of 'face' when dealing with official Burmese. A provincial warlord's attempt at extortion from two British sea captains in Pegu led to the despatch of the 'combustible commodore' Lambert to demand compensation. Lambert ignored Governor General Dalhousie's instructions to avoid conflict and effectively started a war on the Rangoon River. Given the experience of the first Burma war on this occasion the campaign was far better organised and supplied with four steamers to be used on the rivers under the command of Rear Admiral Austen, the brother of Jane Austen. The naval force arrived and under a white flag of truce a steamer approached the Burmese fortifications to seek a response to a somewhat unreasonable ultimatum demanding compensation for military expenses incurred to date and was met with fire from a battery. In consequence, the province of Pegu together with the rich Myéde forests to the north were annexed and retained by the British, though no formal treaty was signed. It was not a very glorious war and somewhat dishonourable to seize and keep territory without the basis of a treaty. Rangoon now became the main hub and all Lower Burma was now under the yoke of the British.

Meanwhile the four steamers that Austen had left behind: the Lord William Bentick built in 1832 in Lambeth, the Damoodah and Nerbuddha built in 1833 in India and the Jumna built also in Lambeth in 1838, the nascent Irrawaddy Flotilla, were manned by officers of the Bengal Marine and lascar crews. They were mainly used for commissariat duties, supplying the garrisons posted at the frontier post of Thayetmyo. In 1885 two of the vessels were seconded to Colonel Phayre's mission to the Court of Ava, meticulously described by Henry Yule in his published account of the mission. They proceeded upstream very slowly on a rising monsoon river reaching Pagan, where four days were spent exploring and sketching the monuments – they were probably the first ever western tourists. They were escorted from Kyauktalon to Mandalay by 150 royal barges rowed by 9000 men in full regalia. Thus the Irrawaddy Flotilla reached Mandalay for the first time in 1855.

In 1863 Arthur Phayre, the Chief Commissioner, decided to sell the four steamers and three flats off to private investors and James Galbraith of Patrick Henderson & Co, who ran ships between Glasgow and New Zealand that would return via Rangoon to load up with rice and teak, formed a partnership with his old friend Thomas Findlay of Todd Findlay and Co who had traded rice and teak out of Moulmein since 1839. Phayre offered sweeteners of mail and supply contracts for the garrison at Thayetmyo and it was a condition that the twice monthly steamer for Thayet had to depart Rangoon within 24 hours of the arrival of the Calcutta mails.

The Irrawaddy Flotilla and Burmese Steam Navigation Company was formed in 1864 with a clear strategy of shipping resources down the rivers, or across the Gulf of Martaban from Moulmein, to be loaded on homeward bound Paddy Henderson ships. Many of the officers and lascars stayed on, now working in what today we call the 'private sector'. James Todd, who covered the Burma end for Todd Findlay, was lost at sea returning to Rangoon from Calcutta after a search for further light draft vessels.

The original steamers were long out of date and poorly designed for the shallow fast waters of the Irrawaddy and it should be remembered that they were all thirty years old and at the end of their lives. It proved necessary to order new vessels, the first being the Colonely Phayre of 1866 built by J&A Inglis of Glasgow, the first of the company's own ships. The development of the company through the design of its ships has been described in another blog and is in itself a fascinating story. Suffice it here to say that in its first twenty years the flotilla grew to thirty steamers and numerous flats with regular routes covering not just lower Burma but also Upper Burma with weekly sailings between Rangoon and Mandalay and twice- monthly sailings to Bhamo and special shallow draft vessels plying the tricky Chindwin.

By 1885 relations had once again broken down between the British, now represented by a Viceroy following the dissolution of the East India Company in 1874, and King Thibaw. During the twenty-five year reign of his father, King Mindon, Burma had 'opened up' to a considerable extent and, with regular river steamer services connecting Mandalay with the world, Burmese had been able to travel to Europe and see what they were dealing with. Likewise, there was now a sizable 'expat' community in Mandalay, which in 1855 had become the new capital, the move said to have been prompted by King Mindon's irritation at hearing the whistles of passing Irrawaddy Flotilla steamers from his palace at Amarapura, the then capital. Mindon promoted trade and was particularly keen on seeing the Bhamo route to China reopened and encouraged the IFC to start services to the Chindwin, opening up an agriculturally rich hinterland. Meanwhile Mindon, had ordered his own flotilla from shipyards in Italy in attempt to compete with the IFC. Whilst Mindon had been a sagacious king and managed to successfully play off British interests against growing French influence at court. His son was less clever and veering towards the French only served to irritate the British. At the same time, under first Louis-Napoleon and then Jules Ferry, France was building an empire in South-East Asia and there was a growing concern that Royal Burma were to become a French protectorate, as had Cochin China and Cambodia in 1862 and 1863 respectively and Tonkin was to in 1887. Not only would the Indian Raj have the French on their eastern border, but the French would control the ever-elusive golden road to China.

Fear of the French coupled with a fear of loss of trade was probably the main reason for the annexation of Upper Burma in the 3rd Anglo Burmese War, but there were several other more ostensible factors including the breakdown of diplomatic relations, commercial extortion and the issue of human rights. The debate over Burma in 1885 was not unlike the debate around invading Iraq in 2003 — the desire to remove an unsavoury regime and prevent further abuse of human rights and a just reward of great riches. There was no doubt that as atrocity heaped upon atrocity, the Thibaw regime even by the practices of the day set new standards for the abuse of power. Initiated with a massacre of the princes, in which over eighty rival claimants were clubbed to death in velvet sacks and then trampled upon by the royal elephants, the regime continued in that vein with several further massacres of would-be opponents. As corruption and the breakdown of order subsumed the country, Thibaw's queen, Supayarlat, personally micromanaged every tiny detail of administration whilst provincial warlords despoiled the country. Refugees, whether princes or peasants, fled to British Burma. Agriculturally rich areas like the Mu Valley went for several years without a harvest, all labour having fled south.

In Glasgow and Manchester, the influential chambers of commerce clamoured for annexation, a call taken up by Lord Randolph Churchill, the foreign secretary. The final straw may have been an arbitrary fine placed on the Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation, who held teak concessions, but the decisive factor in the British decision to invade was a Burmese diplomatic mission to Paris in 1883 and subsequent commercial concessions to the French. Thibaw and his ministers, encouraged by the French, had felt emboldened by recent British setbacks in Afghanistan and Zululand, both in 1879, suggesting that the British were not perhaps so invincible after all.

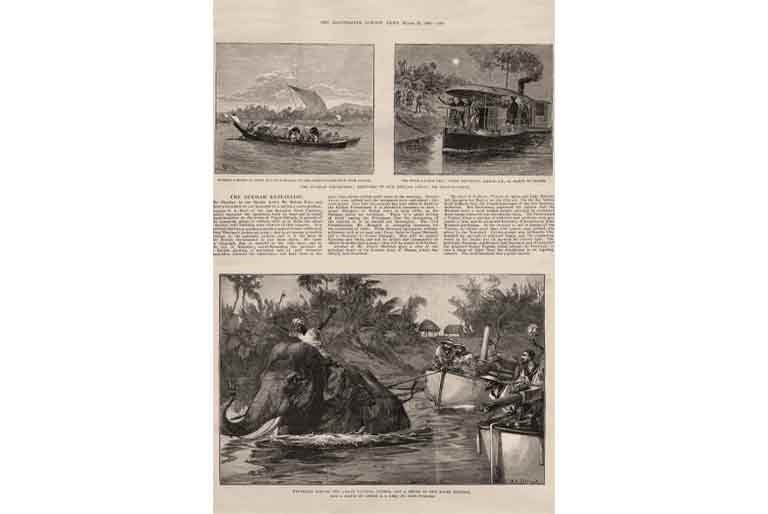

Burma Field Force invading

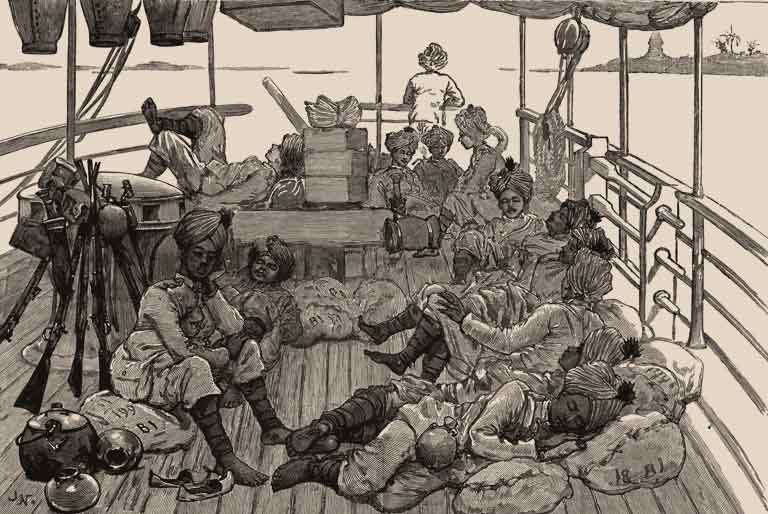

Lascars and Elephant Artillery, 1885

So began the third of the Irrawaddy Flotilla's wars. The fleet was seconded to the Burma Field Force for the transport of troops and supplies in what this time was to be a highly organised and meticulously planned campaign. The India army had been training for this for some time before Britain's ultimatum to Thibaw and the force had been assembled at Madras ready to sail at a moment's notice. Under General Prendergast 10,000 troops were embarked in November and within a week were transferred to the ships of the Irrawaddy Flotilla awaiting in Rangoon. The steamers and flats had been fitted out as troop ships with barracks, canteens, latrines, stabling for horses and there were hospital ships. Guns supplied by the navy were mounted on the steamers and along the sides of flats and a small fleet of steam launches had machine guns mounted on them. The IFC chartered their vessels to the Burma Field Force at Rs 45 per ton for steamers (with coal) and Rs.15 per ton for the flats which at the time was felt to be exorbitant and must have been profitable for the company's shareholders back in Scotland.

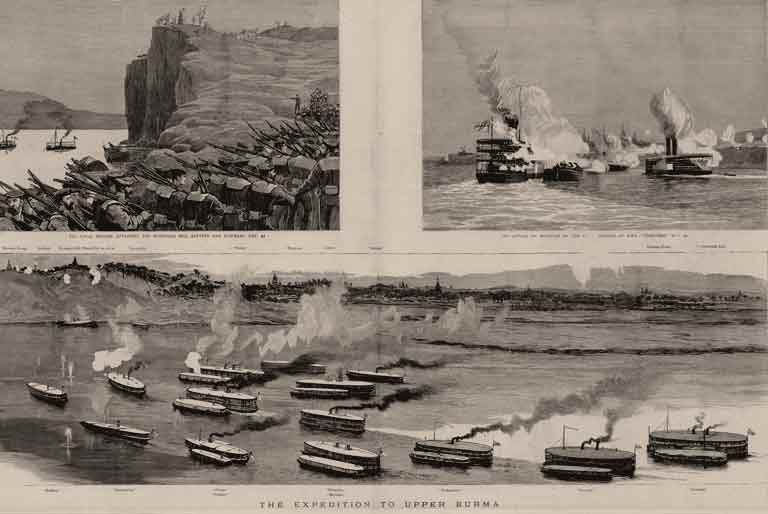

The Third Anglo Burmese War of 1885 was to be a river war with all movement and action confined to the waterway and its banks. To hold the Irrawaddy was to hold Burma and the viceroy Lord Dufferin had given Prendergast strict instructions to attain their goal of dethroning Thibaw "by the display rather than use of force". Speed was of the essence: the fleet rendezvoused at the frontier garrison town of Thayetmyo on 11th November just one week after leaving Madras and four days later the flotilla crossed into Burmese territory. Attempts were made by two Italian military engineers, Camotta and Molinari, to sink two royal ships and block the channel but were captured by the Kathleen and Irrawaddy sent ahead to reconnoitre. Camotta's diaries, detailing the Burmese defences, fell into British hands.

The taking of the fort at Gwechaung

The Burma Field Force, 1885

The main royal defences were two substantial forts built and commanded by Italian engineers at Minhla and Gwechaung. The former was taken easily from the landward side by troops whilst being shelled by long range guns from ships in the river and the garrison of 8,000 Burmese troops disappeared into the interior. At Minhla the Burmese put up more of a fight and a Lieutenant Drury, lamented later by Kipling, and three sepoys fell on the British side and a hundred on the Burmese side. This was the only real action of the war and the flotilla sailed on to take Mandalay without a further shot being fired.

Andrieno, the Italian agent of the IFC in Mandalay, who was close to the court, was instrumental in securing the release of Captain Redman of the Okpho which had been captured near Bhamo and Captain Beckett on the Palow had managed to escape Mandalay disguised as a prize flying a royal peacock flag provided by Andrieno and dressing up his Burmese clerk as a wun or official. No one knew Mandalay better than Andrieno and the Irrawaddy commanders who visited regularly.

Deposing a king is not so easy. First, of all you have to find him in a labyrinthine palace city, and it fell to the Irrawaddy commanders Terndrup and Morgan who knew their away around the palace and court (Mrs Morgan was a great friend of Queen Supayarlat). Morgan led Colonel Sladen to the king in order to handle the delicate negotiations surrounding his departure on the 28th November. The royal family departed the next day, the king walking the mile or so to the river port to board the Thoreah which had been specially prepared for them with an escort from the Liverpool regiment and Naval Brigade. Normally a commander's messing allowance was one rupee a day but Captain Patterson, the Thoreah commander, received an additional allowance of Rs10,000 to entertain the king and his entourage as they sailed downstream to Rangoon. Here they were transferred to the RIMS Clive which sailed for Madras and then Ratnagiri on the 10th December. The Queen Mother and Queen Supayargyi were exiled to distant Tavoy. Thus, within a month an army was able to sail from India, invade a sovereign state and depose a king. Such speed was almost entirely due to the efficiency and effectiveness of the Irrawaddy Flotilla.

The fourth of the Irrawaddy Flotilla's wars was in the 1914-18 First World War when no fewer than sixty-seven ships of the flotilla sailed from Rangoon to Mesopotamia (now Iraq) to assist in the campaign against the Turks there. These included paddle steamers, sternwheelers, tugs, launches, flats and cargo boats – in other words a full flotilla in itself. The commanders and crew went with the vessels which travelled in various groups over the 1914-15 period, some under tow and some under steam heading first for Bombay and then across to Basra. Three were lost on the way: the Tiddim capsized under tow: the Shweli broke her back under steam: the Kelat broke adrift in a cyclone and foundered. As Captain Chubb remarks it was amazing that more were not lost given the dangers of such an undertaking.

On the Tigris the ships were used as troop ships, hospital ships and supply vessels. Two ran bi-weekly carrying mail and personnel between Basra and Amarah. Popa, Pima and Tamu operated as canteen supply ships bringing meals to the soldiers on the front line. Captain Woods wrote of how on his ship the Tantabin, all bed linen and tablecloths were cut up for use as surgical dressings. As General Townshend advanced up the Tigris in an attempt to capture Baghdad, the flotilla delivered supplies and support. The British were forced into retreat by the Turkish army under the command of a German general, Colmar van der Goltz, and were besieged at Kut without supplies. The paddle steamer HMS Julnar, that had belonged to the Euphrates and Tigris Steam Navigation Company, attempted to break through without success and there were even attempts to supply from the air. Townshend surrendered and the British fell back. They were to regain Kut and take Bagdad in 1917. The Mesopotamia campaign, as with the American invasion by the same route in 2000, was all about oil, and like the 3rd Anglo Burmese war was a river war with all advances and retreats, supply and logistics, happening on or along the banks of the Tigris. Sadly, it seems that none of these vessels made it back home to Burma. I wonder if any of them survive today along the ghauts of Basra or Bagdad?

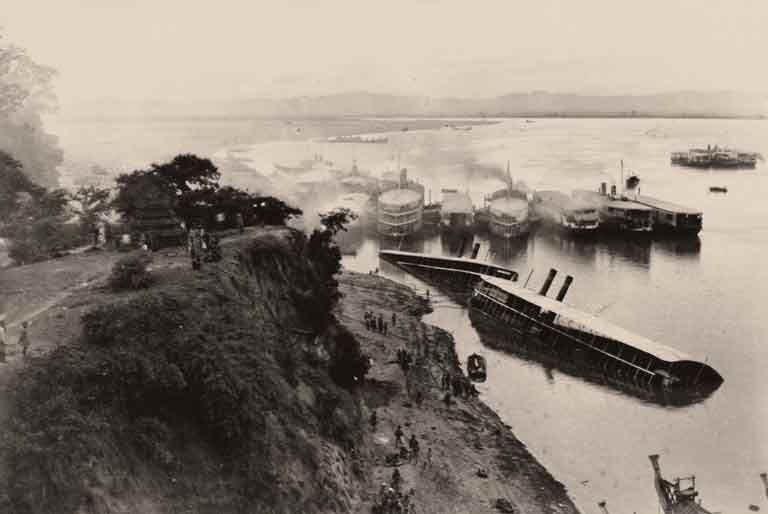

King Thibaw_s ships sunk in the 3rd Anglo Burmese War. 1885

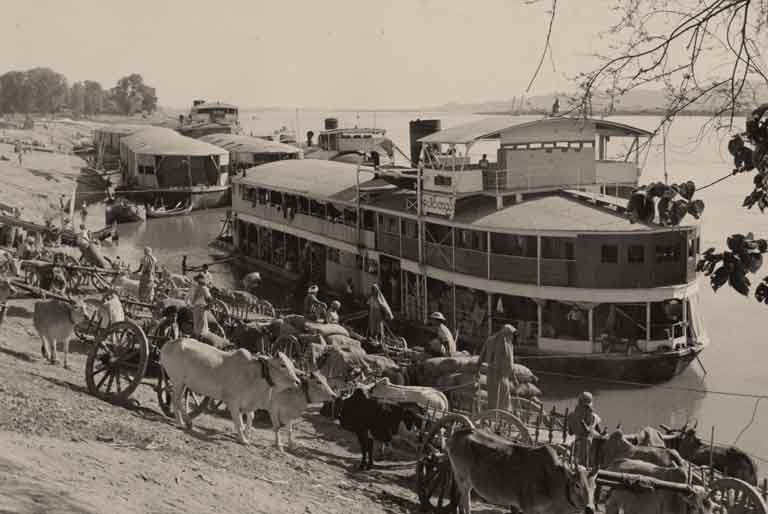

Burmese MInister on his barge (reenacted today)

The Second World War was in the fifth of the flotilla's wars, where it met its tragic demise. It has been said that the scuppering of the fleet in 1942 was the greatest single loss of British merchant shipping ever. Over 500 of a fleet then sitting at 644 vessels were scuppered or sunk in action. Were it not for the Burma Road, built by the British for the Americans to supply Chiang Kai Shek's nationalist armies based in Chengdu, it might be wondered whether the Japanese would have occupied Burma. Japan's war was with the Chinese and it was vital to them to cut of the supply of American materiel to Chiang. This coupled with the Japanese fomenting of Burma's nascent independence movement under student leaders like Aung San, and training them in Japan in Facist military techniques, that are retained by the Tatmadaw to this day, spelt disaster for the totally unprepared British who had traditionally garrisoned their colony with a minute force.

Rangoon had its first air raid on the 23 December 1941 and the steamer Nepaul was attacked from the air, killing its commander and chief engineer. Thereafter one of the most rapid and dramatic evacuations of a country ever occurred. Once again, the river and its flotilla being the main conduit by which the European population, military casualties and retreating forces were evacuated with the Japanese Imperial army hot on their tails. In some case the retreating British would pull out of a town which would be occupied by the Japanese within twenty minutes.

The British operated a scorched earth policy or 'Act of Denial' destroying all infrastructure as they retreated. The Burmah Oil Company refinery at Syriam was blown up and burned for days casting a great black cloud over Rangoon. Port facilities, railways, bridges and of course shipping were all disabled to deny their use to the Japanese. Rangoon, a city of half a million people became a ghost town, the Burmese heading off to the countryside. The British and Indians, first taking what passage they could on sea going ships till they had all left, then headed upriver to cross overland to India. Many did not make it.

Under the general manager, John Morton, a Glaswegian who had been thirty years in Burma with the IFC, a group of assistants and officers joined the 'last ditchers'. Having evacuated their families, they moved into the company office in Phayre Street, conducting demolitions of the flotilla dockyards and port facilities. They co-ordinated the despatch of ammunition and coal barges up river as it was still hoped that the British would hold Upper Burma and these supplies would be essential — in the end, having sent them north, they were to be later 'denied' to the enemy. A small convoy escorted by the tug Panhlaing escaped by the sea route to Akyab and then on to India. The majority of the fleet were trapped in the Irrawaddy and Chindwin rivers and would be pushed further and further up as the Japanese advanced. A great number of creek steamers and vessels were scuppered in Rangoon as they lacked the crews to bring them up country. Sir Eric Yarrow, of the Yarrow shipbuilding family, then a young officer in the Royal Engineers often recounted how much he gleefully blew up Yarrow-built ships knowing that they would get the rebuild orders after the war.

Morton then transferred his staff to Prome where a huge volume of stores needed to be transhipped from the rail head there. Captain Rea, now commissioned into the army, managed to put a brave crew together at Prome and take the Hastings, on a mission behind enemy lines to Henzada carrying Sapper Major 'Mad Mike' Calvert, later a VC and column commander of Wingate's Chindits. Two of the Hastings crew were captured by the Japanese and Rea was awarded an MC for his part in the action.

Captain Chubb, then commanding the Siam, describes how his ship, now painted grey, made a couple of runs to Mandalay loaded with over 5,000 evacuees (the Nepaul was licenced for 3000) and the journey time took fourteen rather than the usual five and a half days as Burmese villagers, then pro Japanese, had cut the channel marker buoys, and he had to stop every four hours for reasons of sanitation. The ship's galleys were working round the clock to feed that many people and outbreak of fires constant. The Nepaul, as with the Mysore, was then converted into a hospital ship, transferring over the staff and equipment of the BOC hospital at Yenanchaung, and they carried nearly 900 casualties from this area to Sagaing for onward transportation up the Chindwin to India. Large red crosses were painted on the roof which the Japanese dive bombers respected. Other vessels were under constant fire. The Sinkan, under the command of a Chittagonian master Bassa Meah, was towing flats of ammunition and when one was hit, Bassah Meah managed to cast it off as the ammunition exploded all around him.

In the retreat, many IFC ships had to be scuttled along the way as the Chittagonian crews deserted and headed for the hills, and on Chubb's last trip on the Siam, a Lieutenant Robertson had his Sikh soldiers working as firemen. Seventy-five ships made it as far north as Katha, these were mainly line steamers with deep drafts. By April the river would have been very low, and it is surprising they got that far. Amazingly there had been a sudden rise in the April which allowed this. The Bhamo office still sent the daily telegram with the water level, and it was this good news that enabled the great ships of the flotilla to continue north. Over 500 of the flotillas were lost in the war, the majority scuppered by their officers. Most ships that fell into Japanese hands were bombed or machine gunned by the RAF in the reconquest.

Morton and his IFC team were the last British to leave Mandalay on 27 April after ferrying the retreating army across the Irrawaddy at Sameikkon. Meanwhile Bhamo was taken by a fast-moving Japanese force and several paddlers fell into Japanese hands before they could be scuttled. The IF agent there, Captain Musgrave, managed to escape overland to Myitkyina from where he was flown out to India.

Stern wheelers with their shallower drafts made it up the Chindwin loaded with the wounded and then acted as ferries to get the army across at ferry points. The most significant of these was the crossing from Shwegyin to Kalewa where the majority of Slim's retreating army were taken over in the eleven sternwheelers of the Chindwin fleet. These were scuppered further up at Sittaung, their officers and crews then legging it to Tamu in India.

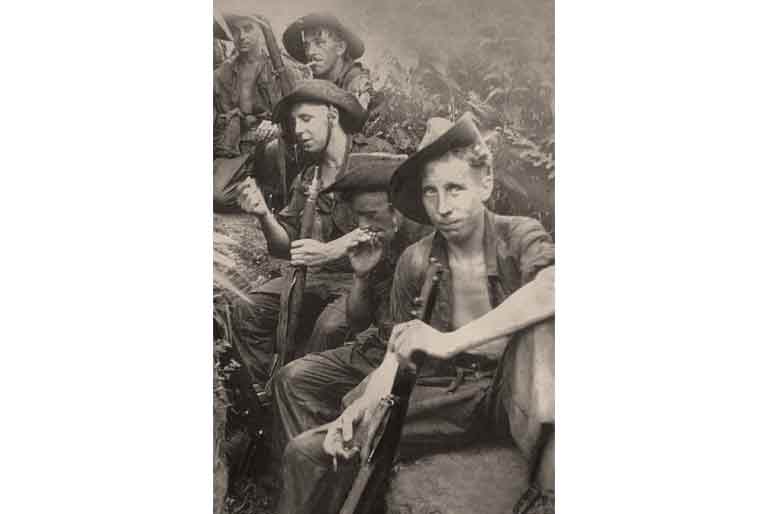

Burma Campaign

Indian Exodus from Burma, 1942

The ships were scuppered by opening the injector valves and machine gunning the waterlines from a boat. Gun cotton placed in the hulls was also used. It is almost impossible to describe the emotion ships commanders must have experienced as they sank the splendid ships they had loved and cared for. They then calmly got into what cars were available and drove west on jungle tracks until their petrol ran out and walked all the way across several mountain ranges and fast rivers till they hit the Chindwin and once across that, over a further mountain range to Imphal. Along these trails lay the dying and the dead. April is Burma's hottest month with temperatures over 40C. John Morton's diary for 3rd May describes the scene at Katha:

Katha is a sight, vessels anchored ten abreast and all deserted. The last train has gone, the town is evacuated. Parties are told-off to sink every vessel, get our three cars ashore first, pay off our Chittagonians and free them to make for Manipur as best they can. It is at least 150 miles to the Chindwin — the cars will not get very far. The day is overcast and the rains not far off. We want low cloud for the Jap planes, but dry for marching — we can't have it both ways.

Again, the last out of Katha were the men of the Irrawaddy Flotilla, their sad duty done with many a broken heart.

Captain Watts of the Mindoon wrote an account which describes a near three-week journey in which they scavenged for food and water, even shooting a hen with a revolver and sharing the water from their canteens with dying evacuees along the way. Most of the flotilla men got out before the rains of June and thereafter malaria and dysentery took care of any stragglers. It was not just the greatest retreat in British military history but the greatest evacuation, far greater than Dunkirk. Dunkirk, which was actually a defeat, was used by propagandists as a tale of British pluck. There was little pluck about Britain's retreat from Burma. It should be remembered that in the Burma Campaign, as with the First Anglo Burmese War of 1824, there were far more casualties from illness than enemy action. In both these wars the real enemy was the mosquito.

Burma Campaign, 1942-45

14th Army in Burma

On arrival in India nearly all the flotilla men immediately signed up and with their local knowledge and understanding of the country had a vital role in Field Marshall Slim and the 14th Army's reconquest of Burma in 1945. A number were decorated and attained high rank. Following the retaking of Burma one of the first priorities was to get what little was left of the flotilla running again to provide vital services and former assistants of the company like Alister McCrae and Stuart Macdonald, with military ranks, were tasked with this. Tragically John Morton, the hero of this tale, who had returned to Scotland by air in 1942 to report to the directors and make plans for a new flotilla, was lost when his ship back went down.

The company set up an office in Simla during the war where they planned for the rebuilding of the fleet after the war and indeed in 1947 over a dozen ships were ordered from Glasgow, six M class main line steamers from Dennys and a number of P class stern wheelers from Yarrows, not doubt to the satisfaction of Eric Yarrow. These were taken over by the Inland Water Transport Board or IWT following the company's nationalisation in 1948 and it has been IWT that continued the flotilla's services, practices and traditions up to the present.

P- class ship delivered in 1948

Katha 1942

The flotilla's wars were by no means over and after Independence as Burma collapsed into an array of civil wars in the 1950s, a number of which continue to this day. The spanking new P class fleet that operated on the Bhamo run were frequently attacked by insurgent forces. One was lost in the deep second defile, mortared by the KIA from the cliff tops above. When I travelled on that route in the mid-eighties, Bren guns pointed out of the saloon windows. When we acquired the original Pandaw in 1998 one of our first tasks was to remove the armoured plating that had been welded around the handrails — the wheelhouse up on its flying bridge was like a pill box with steel plates welded all round so it was quite difficult to see out. Not so long ago I was called by someone in the government and asked to lend a ship for a peace talks with the KIA just over the Kachin state line. It is good to think that ships of the flotilla can be instruments of peace as well as war.

Further Reading:

ATQ Stewart. The Pagoda War: Lord Dufferin and the fall of the Kingdom of Ava 1885 -6. London 1972.

Captain HA Chubb and CLD Duckworth. Irrawaddy Flotilla Company Limited 1865-1950. London 1953.

Frank MacLynn. The Burma Campaign: Disaster into Triumph 1942-45. London 2011.

Alastair McCrae and Alan Prentice. Irrawaddy Flotilla. Paisley 1977.