Back to Homepage / Blogs / Jun 2020

The Irrawaddy Steamer

By Paul Strachan, Pandaw Founder

By the late 1880s, the Irrawaddy Flotilla was the single most important instrument for the opening of Burma to economic development, the rule of law, and its people to the world at large. In no other country at no other time has a single transportation company come to dominate an economy and its administration to such a degree. With over six hundred operational vessels covering just over fifty routings or services, with sixty sub-agencies in the port towns of this great riverine land, the flotilla carried the bulk of the produce of this rich agricultural land down river to waiting ships sailing off to worldwide markets, returning upstream with imported goods sought after by a prospering population. Over six million passengers were carried each year, which represented half the population of the country. People who had never left their villages were travelling up and down river, on business, on Buddhist pilgrimage, or to attend college.

IFC Office Up Country

Mandalay Office

Unlike with other great riverine systems such as North America, or indeed India, the construction of railways in the second half of the 19th century did not put the river steamer out of business but rather complemented it – connecting services and assisting with the transhipment of goods. The fact that the same system established by the IFC by the 1880s, with even the same routings and timetables, continued into the second decade of the 21st century under its successor the Inland Water Transport speaks for itself. Today, whilst passenger transport has dropped off, the rivers remain the most economic method of bulk transportation. This great enterprise was almost entirely Scottish owned and managed, with most of its ships officered by Scots, and was probably the greatest single Scottish enterprise outside Scotland in that small country's history.

The secret of the company's success was naval architecture and the rapid improvement of boiler technology between the 1880s and the early 1900s as much as canny management or commercial opportunism. With constant experimentation and some notable failures, the company in conjunction with the Denny shipyard in Scotland evolved the river steamer to a degree of perfection that has not been surpassed since. Certainly, efficient management and burgeoning demand will have helped, but without the right sort of ship, none of this would have been possible.

Such ships had to have sufficient power to carry enormous loads up rivers against a flow of 10mph or more and maintain control with similar loads going with a fast flow downstream. In one season, a ship might be foundering in three foot of water and by next, caught in a torrent two hundred foot deep. How do you maintain stability when hit by a 100mph cyclone and you have a flat bottom? How do you get alongside a riverbank almost anywhere without the need of jetties or port infrastructure? The solutions reached had consequences not just for the opening of Burma to the world, but in other rivers and other continents. Denny's, Yarrow's and the Clyde yards, which specialised in river vessels, were to take the experience of Burma and the designs they evolved for Burma and apply them to the great rivers of South America and Africa.

The original four ships acquired from the Bengal Marine in 1864 and built in the 1830s by Maudslay & Field in Lambeth and crossed to Burma from Calcutta for the 1852 2nd Anglo Burmese War. They were all about 120 feet long but unsuited to the peculiar conditions of the Irrawaddy and unprofitable. The potential of river navigation had though been realised and the IFC went ordered its own first slightly larger ships in the 1860s from A&J Inglis in Glasgow. These were named the Colonel Fytche and the Colonel Phayre after two of the most prominent colonial administrators of Burma. The ships had design faults with wrongly shaped bows and made poor headway in strong waters. In 1868, the Mandalay was ordered from R Duncans of Glasgow and was considerably larger at two hundred and fifty feet long, twenty-four feet wide with a hull depth of about nine feet drawing about half that when laden. The Mandalay worked well, so as many as twenty side paddlers of this type were ordered throughout the 1870s. With these ships, early design flaws were ironed out. With the exception of the triple decked Thoreah, all were double decked with cargo, boilers and fuel storage in the hull. Decks were open to reduce windage – a real danger in a land of cyclones – and suited to the haphazard placing of passengers who preferred the floor to a chair, their dunnage arranged around them. First class cabins were on the upper deck forward, second class upper deck aft. There was no wheelhouse and the wheel stood open to the elements just aft of the bow area on the main deck. The entire ship would be roofed with corrugated iron like a great barn, keeping all below dry in the monsoon and shaded in the hot season. Jalousies could be rolled down the sides to keep sun or rain out. Some ships had rather attractive rattan matting around the handrails that, allowing air to pass, must have worked well.

This design remained the prototype for most Irrawaddy ships from the 1870s to the present day, and our own Pandaw ships have followed it and maintained the same shallow draft and reduced windage despite the weight of additional cabins. In the 1930s, the M class ferry service ships began to feature flying bridges above for greater visibility, and this practice has continued to this day on nearly all Irrawaddy ships. Of course, the paddles have gone now, greatly reducing the beam which, including the sponsons, would be about a third of the ship's length.

These ships were quick; far quicker than anything on the river today, such was the power of steam and efficiency of a paddle powered craft. Take a trip on the PS Waverly, the last sea-going paddler in the world built in 1947 and still sailing the Clyde. The speed will take your breath away! The fastest ships on the Irrawaddy achieved 15mph on flat water, so on a rapid downstream current, would have been hitting speeds of nearly 30mph over water! (land miles rather than nautical miles are used on inland waters).

By the 1880s there was a sudden leap in confidence and ambition in Irrawaddy ship design under Peter Denny of Dumbarton. This began with larger main line steamers of up to 300 feet in length and a grossing over 1000 tons that were faster and could carry more people and goods than anything before. With the annexation of Upper Burma in 1886, these ships were established into what became known as a 'main line' or 'express' service, carrying mail. The first of these was the Beloo delivered in 1886 that carried the Duke of Clarence (said to be Jack the Ripper) on his India Tour of 1889 under Captain Hole (whose descendants I am in touch with). The Beloo had fine lines that continued through Irrawaddy ship design.

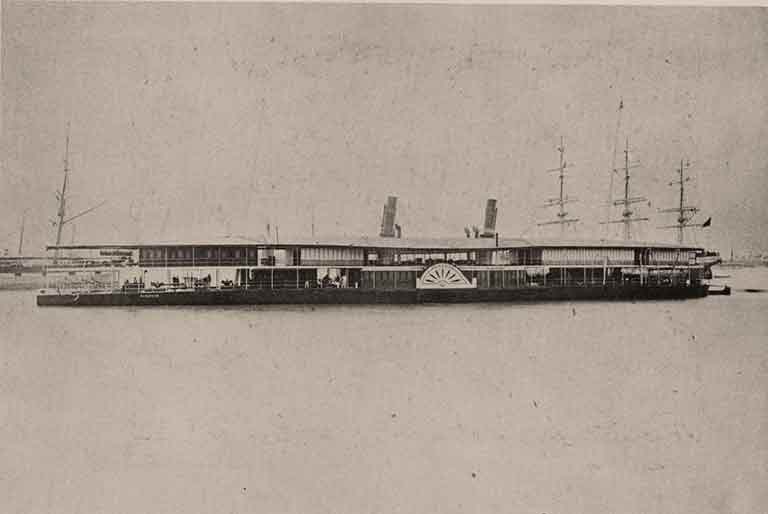

Beeloo

PS Mindoon, 1886, sister to the Beloo

At around the same time in North America, river boats on the Mississippi were attaining similar sizes but in aesthetic terms were very ugly. Given the greater depth of the Mississippi, they could go deeper in draft and wider on the beam and thus have far more space below deck for cargo or accommodation, which made them very heavy and cumbersome and not particularly fast.

As a contrast, the Irrawaddy designs spoke of elan, flair and top speeds. The Beloo Class could carry 3,000 passengers, 500 tons of cargo in its holds and a further 1200 tons of cargo in two side flats. Denny's solution for how to carry great loads at speed was to use far lighter steel, from Bessemer or Siemens, rather than heavy iron plates normally used in ship construction and the IFC was the first shipping company in the world to use steel widely. The paddle floats were made from teak so that if they hit debris, usually sunken logs, they would shatter whereas a damaged steel paddle might twist and contort the mechanism within.

The second jump in ship design under Denny was the development of the shallow draft stern wheeler. These were intended for the Chindwin River reconnoitred in 1882 by Fred Kennedy of the IFC and Annan Bryce of the Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation on a steam launch and declared fit for navigation. Kennedy returned to Scotland and sat down with Peter Denny and worked out a radical solution resulting in the shallowest draft vessels ever constructed, and never achieved since. The Khabyoo was the first of this class, at 170 feet long and 279 gross tons, and was a famous little ship used mainly on the Bhamo run. It was followed by several smaller ships at around 120 feet and far lighter, some with a gross tonnage of just 100 and the lowest draft achieved was just over one foot on a hull depth of just five and a half feet. Nicknamed 'lawnmowers' these stern wheelers were not the prettiest of ships, but in their marvellous simplicity they were extraordinarily clever. The boiler was a locomotive type and placed in the front to balance the weight — when you are hitting sand banks you really want the weight up front. Fuelling took place at stations along the way on a daily basis to reduce carrying heavy weights and save space. Plentiful jungle wood was chopped and ready to be carried on board on the heads of girl porters, then stacked on deck ready for the furnace.

Hata, Sternwheeler

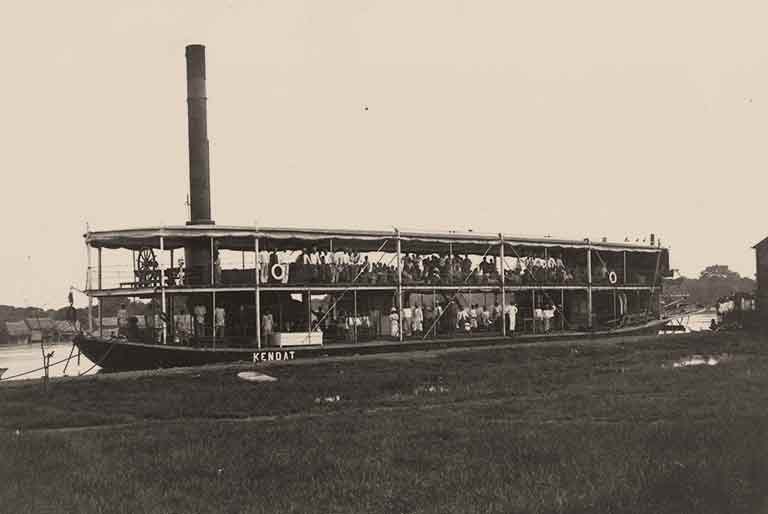

Kendat, Sternwheeler by Yarrow of London, 1886

In 1886, the fleet stood at forty steamers and sixty-four flats but by 1888, the flotilla had grown to over eighty steamers and in excess of one hundred flats with a capital investment over just three years of over £1 million which in today's money would be £130 million. (In today's money, a single Glasgow-built steamer would have cost just over £2.5 million, which seems like good value).

The China of 1888 followed on from the Beloo, going wider on beam and two hundred tons heavier with a single boiler and a draft of just three foot five inches. With rapid improvements in the efficiency of the Navy-type boilers at this time, a single boiler would reduce weight and free up space. There was no longer a need for a second funnel, but the company continued with the second one, because this was popular with their Burmese passengers who might have doubted the power and speed of a puny single funnelled vessel. River ships then still had masts, which were more symbolic than functional. At the same time, searchlights were introduced enabling night navigation and almost halving journey times.

Then in the 1900s, something really dynamic happened – the Siam Class. The Siam was launched in 1903, and the Crown Prince of Siam cruised on her in 1906. At 328 feet long, the exact height of the Shwedagon Pagoda, with a forty-seven foot beam and nine foot seven inches deep, these monsters carried 4,200 passengers (some accounts have it at 5,000) and 2000 tons of cargo in holds and in flats . They were beautiful too, with clean pure lines incorporating the sponsons or paddle housing in an elegant flow. There was nothing in the world to rival this class of steamer in speed, efficiency and majesty. These were the riverine equivalent of the Flying Scotsman, the Blue Ribbon transatlantic liner, the Zeppelin airship.

Each Siam Class ship had eight hydraulic lifts to the cargo deck, first steam and later electric; they had restaurants and canteens; shops and a post office like back in Scotland on MacBrayne's West Coast services, and as with MacBrayne's, a post mark from a flotilla ship became a collectible item. These post offices also acted as saving banks for villagers up and down the river. The twenty-four first-class cabins situated up front on the upper deck were state-of-the-art in comfort and elegance and came with electric fans. The second-class cabins were on the same deck aft. First-class would have been filled with colonial officials, company men on business and globetrotting tourists. Second-class was favoured by Indian and Chinese businessmen.

There were seven Siam Class ships built and all named after other Asian countries: Japan, Siam, Java, India, Assam, Ceylon and the last one in 1909 Nepaul. With a twice weekly service from Rangoon to Mandalay and vice versa, there were always four ships operating, so turnaround in port for unloading and reloading would be a couple of days between each voyage. With increased power and speed coupled with a searchlight and improved channel buoying, the journey time was reduced to five nights. Villagers could set their watches by their arrivals and departures, amazing considering the number of potential impediments to any river journey. Life revolved around the excitement of their arrival and departure and whole towns would come alive when a steamer came in and then go back into deep slumber until the next ship called.

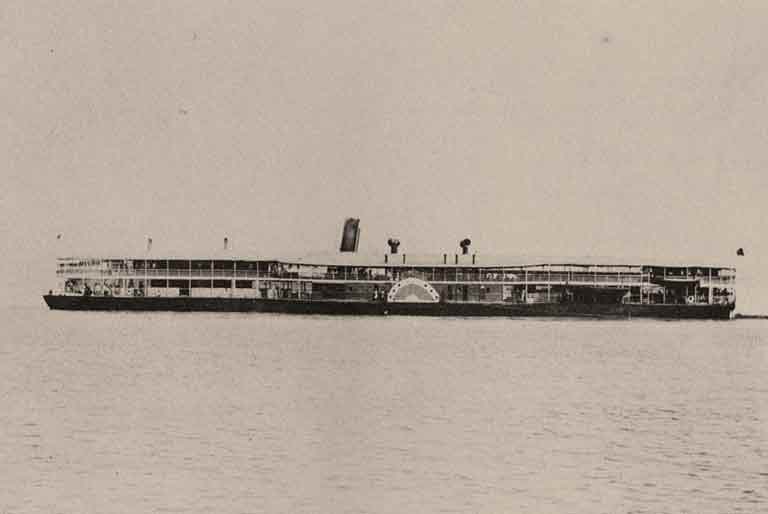

PS India, by Denny1903

PS Japan, by Denny 1904, painted white for the royal visit

It is interesting to note that from the completion of the Nepaul to the Flotilla's demise in 1942 no further ships of this size were ordered. Given the company's high standards of maintenance and care, it was often remarked by travel writers of the day that ships of twenty years age appeared new (something guests on our Pandaws often remark too!). These ships would have a lifetime of at least fifty years. If the company had survived, we might have expected a new class to emerged in the 1950s when curiously, the ever-innovative Denny's were busy inventing the hovercraft!

The use of flats or unpowered barges was very clever and anticipated the age of the shipping container as a way to reduce the money lost while a ship spent time in a port. By towing the bulk of cargo in these flats, they could be dropped off at ports for loading and unloading over a longer period of time. By the heyday of the 1920s there were two hundred flats in the fleet that tended to be known by their numbers. Each flat had its own crew and sukani (helmsman) and the two sukanis would steer in concert with the mother ship which must have been quite an operation. Stories abound of flats being parted as a result of unfocused sukani and axes were kept ready to cut the hawsers to part a flat in an emergency. In times of low water, it might be necessary to drop a flat and carry on with one and then later return for the other. The combined beam of a Siam Class ship across the sponsons and flats was 150 feet – imagine trying to steer that when bombing downstream at 20mph. If you were puttering upstream in your country boat and met this floating metropolis, you got out of the way fast. A speck on the horizon would soon be bearing down upon you, getting bigger and bigger.

Flats had other uses too: in the 3rd Anglo Burmese War, some had batteries of guns mounted on them and others were used as floating barracks for the soldiers or stables for the cavalry. Later, someone came up with the idea of the zay-thinbo or floating bazaar, and this proved popular in more remote areas such as the Mandalay-Bhamo run where stalls were prized possessions handed down by their keepers from generation to generation.

The Creek Steamer designed to operate in the vast 10,000 square mile Irrawaddy Delta was the most prolific of all the company's ships. Over one hundred and seventy were built and in 1941 there were no less than sixty services or routings offered to the Delta towns. These double-decked ships ranged from eighty feet to one hundred and fifteen feet long and were twin screwed as the creeks were often too narrow for paddlers. In addition to these steamers, a number of local operators, such as the single decked launches of Chander Pal, were absorbed into the fleet and an array of vessels was used as ferries and short-distance services between villages, tugs and inspection launches.

Gozo, a Creek Steamer, built by Denny 1923

Scene from the Rangoon River

Prior to the arrival of the British, the Delta had been an area of jungle and swamp, but using Indian Chetty finance and Tamil seasonal labour, the settlement of Karen communities, and an investment in canals for drainage and irrigation, the Delta was to develop into the 'rice basket of Asia'. There were few roads or bridges, and this enormous tonnage had to be transported to seaports at Rangoon or Bassein by water. The Rangoon-Bassein overnight service offered first class accommodation and until recently remained the usual way of travelling down there.

Nearly all the creek steamers had an 'o' at the end of their name and there was a Zero, Grotto, Pluto and I recall finding a Braco, named after the Perthshire village of that name, still running in the 1990s. Names could be witty too, there were two ships named Porto and Bello, after the home town of the company's marine superintendent – Portobello! A number crossed to Mesopotamia during the 1st World War, some making it back and some not.

The creek steamers tended to have Chittagonian masters rather than Europeans and there were considerable problems with lost earnings, so the company deployed a number of high-speed patrol boats in the delta called 'inspection launches'. On board would be an 'assistant' as the young Scots managers were called, who would be quartered for months on end in a cabin screened against mosquitos, which in the Delta are said to be amongst the virulent in the world. His job was to pounce on steamers for ticket checks and cash counts. Snipe, Hawk, Wren and Rover were all designed for high-speed chases through the tight winding Delta channels. Assistants would often lie await up some creek and ambush a passing steamer before the purser had time to tidy up his books.

Up until the 1930s, when the IFC started building ships in Burma, the bulk of the fleet had been built at yards on the Clyde, with Denny of Dumbarton as the main builder but with Yarrow's and other yards specialising in river vessels, building a number of the more shallow draft vessels. Though a few sailed out to Burma under their own steam, boarded up along the sides, most were sent out as 'kits' and reassembled in the IFC dockyard at Dalla. 'Reassembled' because they were assembled first on the Clyde for classing and it should be noted that all IFC ships had Glasgow as their port of registry. Port side plates were painted green and starboard side plates were painted red and of course numbered corresponding to blue-print plans sent out with them. This was Airfix modelling on a grand scale! The boilers and engines would follow on a later ship and, together with the ship's davits, be lifted from their holds straight into the steamer's hull, which had been floated and brought alongside the ship moored midstream in the Rangoon River. Such clever, simple 'Scottish' solutions saved enormous amounts of money.

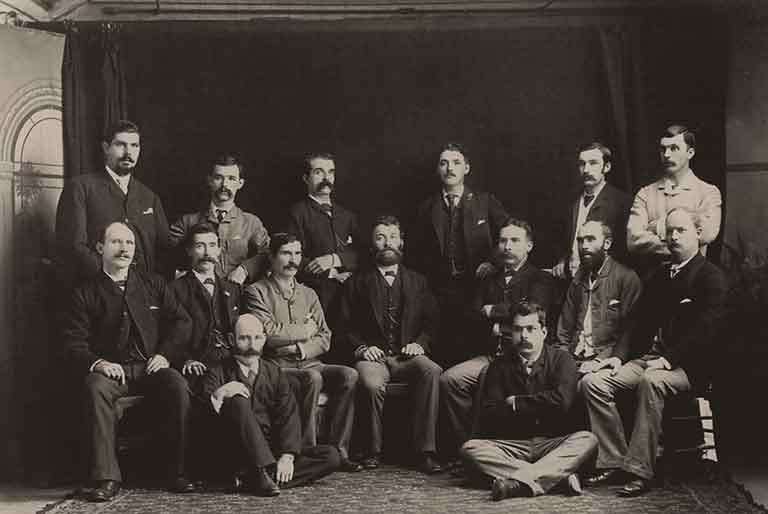

Dalla Staff, 1880s

Dalla - Kobe under construction

The Dalla Dockyard was a vast complex on the opposite bank of the Rangoon River facing the city. Ships had been built at Dalla right back to Portuguese times in the 16th and 17th centuries and it should be remembered that Europe's interest in Burma was for its teak. By the 18th century, when both England and France had cut down their own forests to supply a century of naval warfare, each country's motivation in gaining a foothold in Burma was for shipbuilding. The company acquired the lease of the land at Dalla in 1874 and in its heyday employed over 2,5000 workers under a superintendent, with engineers invariably from Dumbarton and trained at Dennys.

In addition to the reassembly of ships sent out, Dalla undertook the repairs and refits of all ships and given their longevity, this must have been to a high and exacting standard. Engine failures were virtually unknown. The Dockyard offered ship repairs to ocean-going vessels who could fly a particular flag in port to summon a standby engineer who would appear on a fast launch. The company took over the Rangoon Foundry at Athlone in 1904, with a further 1000 employees, and had dockyards at Moulmein and Mandalay, the latter of which had been built by King Mindon for his fleet of Italian steamers, mostly sunk in the 3rd Anglo Burmese War. In 1933, the Pazundaung Foundry was purchased from Bulloch Brothers resulting that the company had a near monopoly not just of river transportation, but also ship building and repair. This was what was needed to keep six hundred ships up and running – dockyards, foundries and literally thousands of workers under a team of Dumbarton men.

Dalla Fire Engine

Rangoon River Scenes

By the 1930s, the IFC was building new ships at Dalla rather than shipping out from Scotland and that doubtlessly would have been the direction in which the company had been moving had it not been for the war. During the war, most of the facilities were destroyed in an 'act of denial' by the company's officers along with most other infrastructure as part of an earth scorching retreat by the British. Dalla is still on the go, run by IWT and I have stood there under many a ship pulled up on the slip, sparks flying as welders patch a hull.

Most of the fleet ran on coal and whilst there were coal mines up country, the bulk of coal was shipped into Rangoon from Calcutta and coal mines in India. The company was one of the first to burn fuel oil in their boilers which was readily available as a waste product from the oil refineries. However, as the refining process improved, by 1924 this was no longer available, and they reverted to coal. In the First World War, with a shortage of coal, boilers were converted to burn oil cake, an agricultural product from the Dry Zone of Middle Burma made up from compounded ground nuts and usually exported as animal fodder. So another first was the use of bio-fuels! As mentioned, the Chindwin sternwheelers with their locomotive engines ran on firewood. With the construction of the Ava Bridge in 1931, funnels had to be shortened, fitted with cowls or nets to catch the sparks. This certainly improved the appearance of the older sternwheelers which had disproportionately tall funnels. Note that all funnels were painted black and red – the IFC house colours and apparently so because these were the cheapest colours of paint available. The IWT have continued with these colours on their ships to this day, and when we used them, we got into a spot of trouble and had to repaint the black navy blue.

In addition to the main line or express steamers, 'cargo steamers' plied the same routes and were effectively the slow boats stopping at every village. Many tourists preferred the cargo service, which had a first class, as a way to really get to know the country which in 1941 took eight days up and seven days down between Rangoon and Mandalay rather than 4 days on a main liner.

There were also the 'ferry services' that operated between various Irrawaddy towns and the 400-mile ferry journey from Prome to Mandalay took three nights. Interestingly, the timetables of the ferry services were arranged around court timetables, with the Burmese, and moreover the Indian business community, happily embracing the joys and excitement of the British legal system. FCV Foucar, a British lawyer practicing in 1930s Burma, describes how many of his Indian merchant clients would always have several lawsuits on the go at any one time in the hope that at least one would be successful. Happy times for lawyers! The ships on the ferry services evolved into the M-class of 1927 which were fast and efficient at about 200 feet long and the half dozen delivered shortly after the war were still running till a couple of years ago. The Ms were proud, swift vessels with their flying bridges and elegant lines and can still be spotted laid up and forgotten along the fringes of IWT dockyards.

The other river system where the company operated was out of Moulmein on the Salween going up to Hpa-an, and the Ataran to Kyondoe both deep in Karen State. These services were on so-called 'launches' which could be 100 feet plus long and given local competition, they were designed to be very fast. Interestingly, when the flotilla acquired Mr Dawson's fleet of steam launches in 1885, they also acquired a railway Dawson had built between Thaton and Duyinzeik to connect Thaton with the coast where his ships came in.

It is curious that the company never traded in the Arakan - surely a perfect location for IFC activity with numerous rivers connecting a rich agricultural hinterland, not to mention a labyrinth of coastal creeks and estuaries. There was an Arakan Flotilla Company that, like the IFC, was nationalised in 1948 after Independence. This ran numerous services along the coast and backwaters of this riverine state. The IWT 'Handbook' of 1962 has the timetables for these services which must have been identical to those of her predecessor. There is little known of this company and its ships and I would welcome any information. I have a hunch that it may have been an offshoot of the multitudinous British India Steam Navigation Company, whose ships called at Akyab.

In the 1930s the main direction in which the company moved was aviation with the formation of Burma's first airline in 1934 – Irrawaddy Flotilla and Airways. This was managed and pilots provided by Imperial Airways, which became BOAC and was later merged into BA. The IFC also acted as Rangoon agents for Imperial Airways. Four Shorts Scion sea planes were ordered from Northern Ireland. The intention was to provide an airmail service up and down the river, however the expected government contract was never won, and the service remained unprofitable. In the end, this novelty became popular with Burmese keen on joy rides and pleasure trips. There was one occasion when a plane was overloaded and could not take off and taxiing back, a lady got off to lighten the load. It was then rumoured that the airline would not carry women and the company had to offer several Burmese ladies free trips to dispel this myth. A popular trip was a pilgrimage flight to the Magwe Pagoda where the aircraft auspiciously circled the pagoda seven times. Eventually after the loss of two aircraft it was decided to disband this unprofitable venture. Interestingly one of the pilots, Captain Esmonde, went on to win a posthumous VC for his part in the sinking of the Scharnhorst.

IF and Airways Advert

Mail drop for the Prince of Wales, 1934

In its near eighty years of operations, the IFC and its ship building partners remained at the forefront of naval architecture and technical innovation as applied to inland water steamers. Burma was no backwater: here on the rivers, creative minds and innovative spirits were at the cutting edge of technical developments that had ramifications for the shipping industry across the world and set design prototypes for river navigation on all continents. Great loads and large numbers of passengers were carried in challenging conditions in safety and considerable comfort. This is a point to note – although inevitably there were occasions when ships foundered on rocks or sands, collided with other vessels, and even caught fire, the company successfully carried six million people a year for the better part of a century without loss of life.