Back to Homepage / Blogs / Nov 2020

The Business: how did they run the Irrawaddy Flotilla?

By Paul Strachan, Pandaw Founder

Having struggled over the past twenty-five years to keep a few boats running on the Irrawaddy river it defies understanding quite how the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company managed to keep several hundred running. To find people with the right skill set to undertake such challenges must in itself have been a challenge. Responsibilities were huge, you could not sit in Scotland and micromanage an operation using Whatsapp (as I do). You could not hop on a plane if there was trouble. Whether a letter from head office or a visit from a director, it took a month to get there by steamer and a month back. The telegraph was prohibitively expensive and only used in emergencies. Managers were thus on their own and had considerable latitude to make on-the-spot decisions without recourse to head office. Perhaps this is why it all worked so well!

Typically, 'assistants' as managers were called came from the West of Scotland middle class families and were well educated in one of Glasgow's celebrated academies. They were rarely university men, and few had been public school educated. I am of an age where I was fortunate enough to have met the last generation of Scots who served in the Flotilla. In the late 1980s I got to know Alister McCrae then in his seventies who lived in Killearn, quite close to where my parents lived, and our families knew each other well. He was typical recruit for the Flotilla, his father was a well-established timber merchant and he was educated at the Glasgow High School joining Patrick Henderson & Co in 1927 and serving in the accounts department at their St Vincent Street offices. Paddy Henderson was a shipping line and part owned the IFC and whose office was also the registered office of the IFC. In 1930, at the age of twenty-one, Alister was transferred to the IFC secretariat in the same Glasgow office. Here a staff of just three managed the affairs of one of the largest companies in Scotland liaising between head office in Rangoon and the directors in Scotland, who in those days would be what we now call 'non-executive'. Henderson's recruits were watched over and if of high enough standard 'invited' to go out to Burma and join the IFC. It is notable that they had their basic training in accounting.

In 1933, Alister was eventually selected and went out to Burma and after a stint in the 'Cash Department' at head office in Phayre Street was sent off to manage operations in often remote areas with little or no contact with the office other than letters and written reports. Living for months on end in a fast Delta patrol boat, heavily screened against mosquitos, he raced around the creeks pouncing on Lascar-commanded steamers for ticket inspections and cash counts. It was said that it took a minimum of six months in the Delta just to understand its complexity.

Reading Alister's 'memoir' of his time in Burma in the 1930s, what comes over is the high calibre of these young men and the fact that they mostly came from distinguished Scottish families: Charles Bruce, son of Sir Robert Bruce, Editor of the Glasgow Herald; John Roberton, whose father Sir Hugh Roberton was founder of the famous Glasgow Orpheus Choir; Christopher Lormier, son of the distinguished architect Sir Robert Lorimer; Charlie Cowie whose son became the famous Scottish High Court Judge, Lord Cowie.

These young Scots were steady characters, self-disciplined and nearly all deeply sympathetic to the Burmese and their world. Required to learn Hindi, to be able talk to crew, and Burmese to talk with passengers, they received bonuses on passing exams in these subjects. Consequently, they could freely interact with the Burmese and as I have discovered, when you know the language, you really know what is going on. It is customary to talk of 'dour Scots' but I do not think any of them were very dour, not the ones I met. Rather they were outgoing, very social, and keen golfers. They worked five years in the country and then were granted passage home for six months furlough and were not allowed to get married until their second furlough after ten years when they would bring their bride back to Rangoon. No assistant ever took a Burmese wife, though a number of officers and engineers did, and they were perhaps a little bit 'goody goody' resisting the temptations of the east. One assistant who married on his first furlough back in Scotland and on returning to Rangoon with his new bride was dismissed on the spot. The company was equally intolerant of any form of incompetence and preferred a small close- knit team of sharp, focused men to a bureaucracy of dead wood and time servers.

Living in a 'chummery' called Irrawaddy House which was part of the company's residential estate at Belmont, the unmarried assistants in their spare time played rugby, tennis and golf. The Scots Kirk was just across the road and in the moral mire that was (and is) the port city of Rangoon these Presbyterian lads lived cleanly and for that reason earned the respect and admiration of often prim Burmese. For chummery read commanderie, as the assistants were the Templars of colonial commerce.

There were just twenty assistants, half of whom would at any time have been on leave, sick or on furlough. So just ten men ran over six hundred vessels with 5,000 crew, five dockyards with a further 5,000 workers and a mostly Scottish expatriate team of two hundred officers and engineers. Sent to Mandalay at the age of twenty-nine, Alister managed the main transport infrastructure for an area the size of Scotland and was allowed one telegram a month with one line – the monthly takings. There was a telephone but picking it up and calling head office was regarded as the ultimate sign of failure, so it was rarely used.

Within the country 'assistants' took their leave in one of the hill stations. The largest, Maymyo at 3,000 feet had a good golf course and apparently the largest man-made network of bridle paths in the world. On the river they shot duck on the sand flats and fished for giant Mahseer in the rapids. Only the superintendent of pilotage went back annually during the monsoon when pilotage operations were suspended to make a report to the directors. Travelling widely around the country the 'flotilla men' possessed a knowledge and understanding of Burma that made them very useful in the war, nearly all being commissioned into the 14th Army and a number being decorated for distinguished service. After the war they all went on to having distinguished second careers, Alister re-joining the Paddy Henderson office in Glasgow as a partner and later becoming chairman of the Clyde Port Authority.

Whilst the great commercial success of the Flotilla might be attributed to either market conditions or the clever design of ships none of this would have been possible without robust management. A succession of highly capable and often visionary managers in late 19th century created the structure and ethos that was to continue until the Flotilla's demise. The motivator behind the rapid early development of the company through the 1870s was James Galbraith of Strathaven who never visited Burma and managed from his Glasgow office the affairs not just of the Irrawaddy Flotilla, but also the shipping lines Patrick Henderson and Co and the Albion Line, not to mention a variety of other colonial interests such as the Rangoon Oil Company. Galbraith was the epitome of the great Glasgow entrepreneur, managing diverse companies that all interlinked through business operations and the investors backing them. This was not untypical of shipping circles in the West of Scotland where the ship owner, builder, financier, insurer and charterers were all part of a small circle, often intermarried, and in some cases you would find that a member, like the ship builder Peter Denny of Dumbarton, might be actively involved in all of these activities.

Galbraith had joined Henderson's as a clerk in 1844 when he was twenty-six years of age and was made partner within four years where he remained until his death in 1885. In 1876 he effectively took the company public, floating shares on the Glasgow stock exchange and the take up was, and remained till the company's demise, almost entirely by investors from Glasgow and the West of Scotland. Thus, the largest privately-owned fleet in the world and Scotland's greatest ever overseas commercial endeavour was entirely owned, managed and operated from within a relatively confined geographical area.

Whilst Galbraith raised the finance, made the connections and built up the fleet from Clyde shipyards, particularly Denny's of Dumbarton, the day-to-day running of the company was in the hands of a manager in Rangoon. The company was fortunate in having a succession of highly able men in that position, each of whom nurtured his assistants to ensure a flow of capable successors. Able men tend to promote other able men, whilst incompetent managers tend to appoint managers even less competent than themselves. The success of the flotilla was that the former course was followed.

George Jameson Swan from Perthshire was the first of these great managers, coming out in 1867 at the age of twenty-seven from Henderson's office to manage the Flotilla's accounts under the agency of Todd Findlay and Co. Within a couple of years, Swan was managing the entire fleet. With the formation of the new company in 1876 he was to set up his own office as Todd Findlay had resigned as agents following the collapse of their business with the crash in 1878 of the City of Glasgow Bank. Swan now had the freedom to set up a structure that would endure for the next sixty years and indeed was followed by the nationalised IFC after Independence up till the present. Swan oversaw the terrific expansion of the fleet through the 1870s and 80s from eleven paddlers and thirty-two flats in 1875 to nearly two hundred vessels by 1888. He was assisted by Frederick Charles Kennedy, a civil engineer from Leith whom Galbraith recruited in 1877. Fred Kennedy, as with all assistants joining, was given a sound training in book-keeping and his first appointment was as 'cashier' in Rangoon. Given the proclivity for money just to seep away in Burma, financial discipline was essential and one of the twin pillars upon which the company was founded, the other being ship maintenance. By the 1880s Swan was spending only the winter months in Burma, returning to Scotland for the rest of the year and Kennedy became manager in Burma.

Undertaking several river expeditions across the Delta, up the Irrawaddy to Bhamo and then the Chindwin river in 1881 Kennedy opened new routes on these rivers and effectively opened up large parts of the country to cultivation and trade during the reign of King Mindon. Galbraith had died in 1886 and Peter Denny had become Chairman continuing growth and expansion. Kennedy retired in 1896 returning to Edinburgh where he was to die in 1916 at the age of fifty-six. During his tenure as manager he had increased the fleet from two hundred vessels to five hundred, so it is not surprising that he was worn out.

As mentioned, the 'assistants' usually came from a strong background of bookkeeping and accounting in Henderson's Glasgow office which was reinforced by time served in the Cash Department at head office in Rangoon before they were let loose up country. Management was thus very much about financial discipline in a totally cash based economy. In my days working with the IFC's successor the IWT (Inland Water Transport) I used to visit the Cash Department in the Phayre Street office (now Pansodan Road) to make payments. Presided over by a slightly scary Anglo Burmese lady, there was an enormous strong room with a steel door a foot thick where all the money would have been kept. It was pretty empty whenever I visited.

The operation of the flotilla was left to three senior superintendents: marine, dockyard and pilotage. The marine super would supervise commanders and officers and ensure all vessels were well maintained and safely operated. Usually this position would be filled by a senior captain who had experienced many years, often decades, on the river. Most commanders were experienced men of a sea-going background and recruited through Henderson's office in Glasgow to be sent out to serve a year as a first officer learning the river. The fact that in a single year the company could carry half the population of the country without loss of life in some of the world's most hazardous waterways speaks volumes.

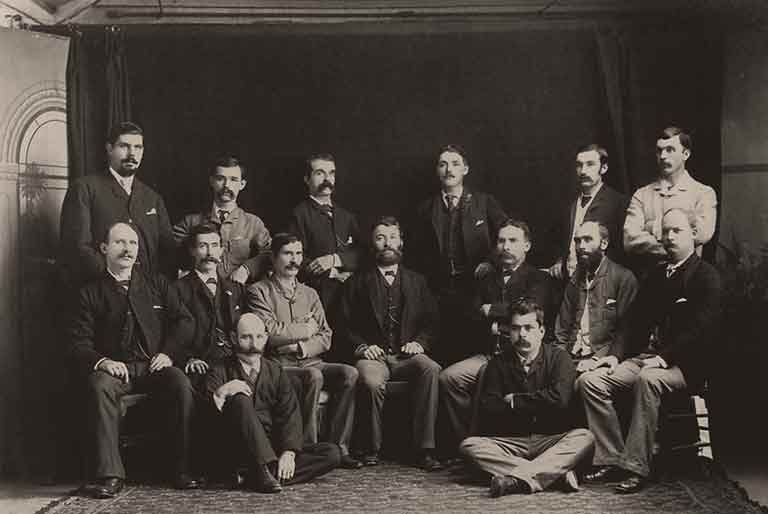

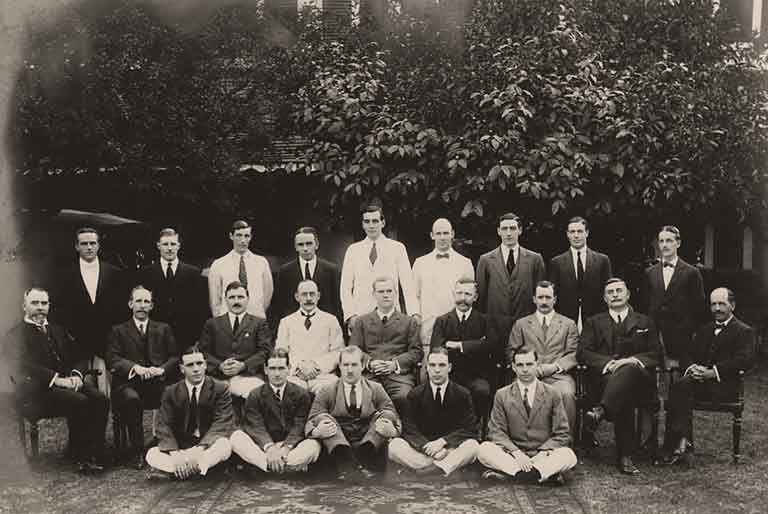

Dalla Staff, 1880s

Dalla Dockyard

The superintendent of dockyards took care of the company's four yards at Dalla, Athlone, Moulmein, and Mandalay. Under him engineers, almost entirely from Dumbarton who had served their time at Denny's, assembled the ships from kits sent out from the Clyde, installing the boilers shipped out later and lifted into the now floating hulls direct from the holds of cargo ships moored in the Rangoon River. They maintained the fleet to a high level and mechanical breakdowns were almost unknown. Well maintained, these ships would have a lifespan of as much as fifty years. Dalla also offered repairs to sea-going vessels and by the 1930s was beginning to build ships from scratch, a trend that would have continued had the war not interrupted. Five thousand workers were employed in the company dockyards, as many men as served on the ships, which gives some idea of the importance of maintenance.

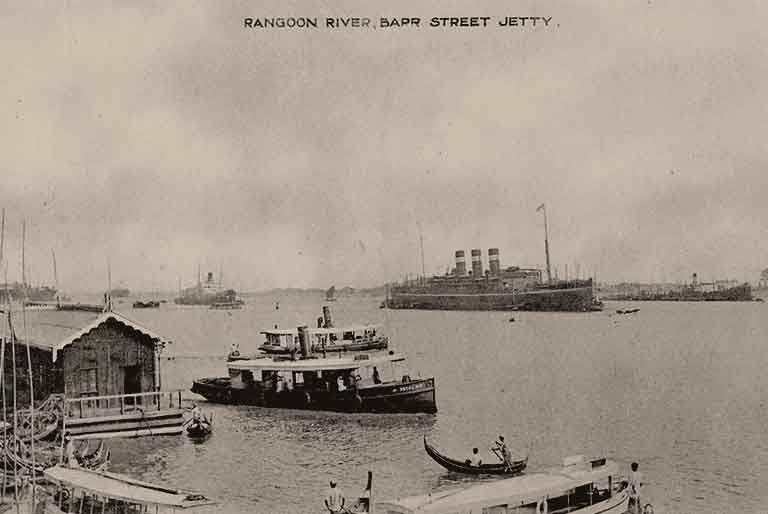

Barr Street Jetty looking across the Rangoon River to Dalla

Dalla Fire Engine

The superintendent of pilots took care of the buoying of the river and lived on his own 'pilot launch' patrolling the river and using floating bamboo poles and riverbank markers to guide commanders on the river. This was a free service to all other users of the river. The Chindwin had its own superintendent of pilots and in the 1930s Stanley White, known as 'Chindwin White' lived on his own little steamer plying the river poking bamboo poles and flags in the strangest of places. During the high waters of the monsoon there was no need for pilotage, and pilot superintendents were allowed home leave in recompense for a lonely several months.

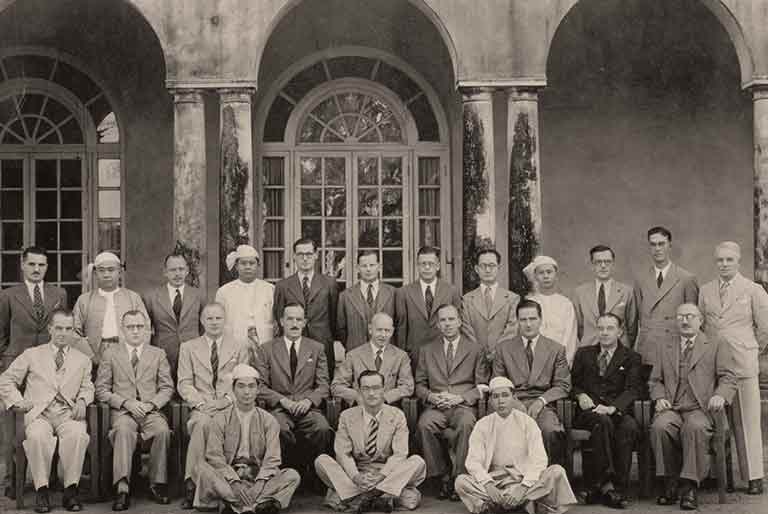

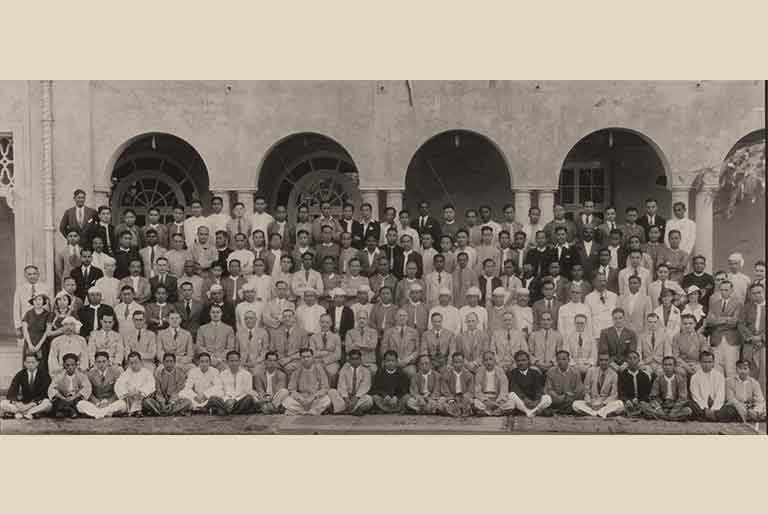

Office staff 1947, Alister McCrae centre row, 4th from right

Alister McCrae's house in Mandalay

Each river town in Burma had its Irrawaddy kozalay or agent who was well housed, usually in a roomy 'dak' bungalow within the civil lines whilst his godown and office were on the river's bund. This was a highly respected and important position and often the prerequisite of senior captains on retirement. In places like Pagan or Bhamo they acted as tourist information offices, some like Captain Medd in Bhamo were tourist attractions in themselves with tales of the Irrawaddy in times of peace and war. Larger ports like Mandalay or Moulmein would have an 'assistant' assigned as agent as with Alister McCrae who was sent to Mandalay. These larger agencies had a dockyard under the ubiquitous Dumbarton engineer and with a network of routings converging there, they were essentially regional hubs. Alister would go down to the Strand Road early each morning to watch the steamers depart, always a moment of great excitement with the parting cries of well-wishers, the mischievous jokes and repartee between sailors and stevedores, the cackling of the hawkers, the hoot of the horn and in those days the wonderful whoosh as the boilers got up steam; and let's not forget that very Kiplingesque clunk of paddles. That was my job too for many years as I would see ships off, the whoosh and clunk being replaced a diesel throb, but the crowd and its craic much the same.

The first Belwood, c.1875

Inside the second Belwood

Married assistants were also well housed, in Rangoon at the Belmont Estate at Kandawgalay which George Swan had purchased in 1875. Belmont was the house of the manager and the first Belmont was a classic timber built dak house later to be replaced in the 1930s by a sprawling brick house. Senior assistants lived on the estate in Belwood, Belstone and Belfield, all large houses but not as grand as Belmont. After nationalisation, the estate's lease passed to the British foreign office and Belwood houses the British Ambassador and the other houses embassy staff. Belfield is, I think, now the British Club with truly awful food.

At Dalla the superintendent and his engineers were housed in bungalows overlooking the Rangoon River and today the Burmese engineers of IWT occupy them. The company's estate across the country was considerable: whether agent's houses and offices or dock yards but the grandest building of them all was head office in Phayre Street. This was rebuilt, as indeed much of Phayre Street was, in the 1930s, superseding the original neo-colonial office building of the 1870s. Designed by AG Bray in 1933 in the grand corporate style of the period it remains one of the main landmarks of downtown Rangoon. Situated on the first floor up a monumental white marble staircase was the teak panelled assistants meeting room. In the 1990s I often found myself there in interminable meetings about fuel supply and spare parts. As I drifted off, I could just see the assistants sitting round the same table only discussing more exciting things like the prospects of the new airline they had just started.

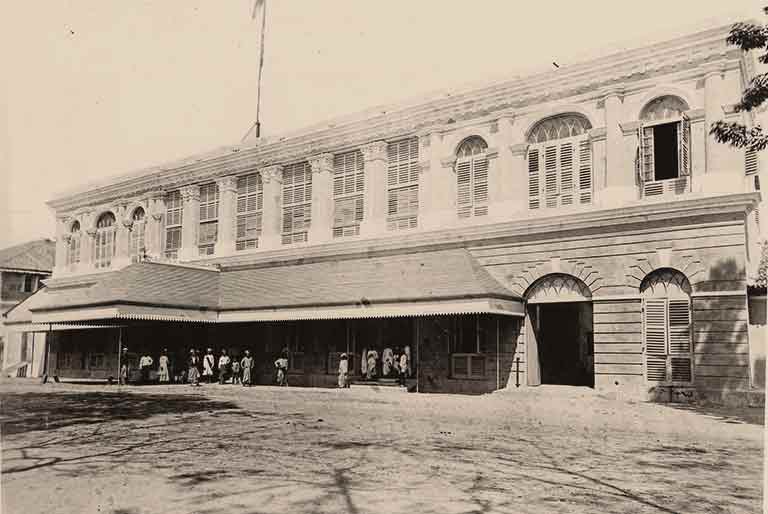

The original Rangoon offices

Phayre Street office completed in 1933

Contrary to what is taught in Burmese schools today the IFC was not a monopoly. Though the IFC was the largest operator of inland water ships in Burma there was plenty of competition and the company had to stay ahead of the game. In addition to numerous local operators of country boats, barges and all manner of craft that carried a considerable volume of passengers and cargo, there were a number of attempts to set up steamer services that would compete with the company on key routings.

The first of these was King Mindon's fleet of river steamers ordered from Italy in the 1870s. One of these was said to have sailed out loaded up with Venetian furnishings for his new Italian style palace being built in the new capital he founded at Mandalay in 1857. These vessels were never operated commercially but from time to time raced against each other along the Mandalay river front, a spectacle much enjoyed by the king. In the Third Anglo Burmese War some were sunk as a result of military action and the survivors later absorbed into the IFC.

The main challenges came from the wealthy Indian business community and the Burma River Transport Company formed in 1910 who operated twenty-two steamers and a fleet oil flats. Their ships were technically ahead of the IFC and faster, so the company built the Otara and Osaka with the latest water tube boilers that achieved speeds of 15.5 knots. These were known as shadow steamers as they would shadow a competitor and then nip round and get into port first for first pick of passengers and goods. A situation developed not unlike what was common on the West Coast of Scotland with competing captains racing to get into port first and taking daring short cuts at some risk. Needless to say, the Burmese would have loved the excitement and drama of this but ultimately the winner was the company that could keep lowering ticket prices and had the deepest pockets. At one point the IFC were not only offering free tickets but also free meals and eventually the Burma River Transport Company went into liquidation and its steamers were bought up by the IFC to be absorbed into the fleet. In 1913, the Delta Navigation Company was acquired by Kennedy as was in 1916 Gulab Hussein Atcha's fleet operating out of Bassein. Each had successfully competed on popular IFC routings in the Delta areas and happily for the owners, Kennedy bought them out.

Every Burmese school child knows the story of U Nar Auk, a former cattle herder who became a millionaire in Mon state with timber and banking interests and wished to challenge what was perceived as Indian and British exploitation of the Burmese peasant with a fully Burmese-owned flotilla company. The Burmese Steam Navigation and Trading Company of 1910 operated out of Moulmein on the Salween and Ataran river systems. U Nar Auk was, though, a devout Buddhist and gave free passage to monks and nuns who tended to take up a lot of deck space. Further revenue was lost as the IFC inevitably undercut him and even gave passengers presents. There were dockside battles over loading and unloading and subsequent lawsuits. The story of the collapse of U Nar Auk's frustrated enterprise today forms part of all Burmese children's history syllabus and in many respects the populist decision by the newly independent government to nationalise the IFC in 1948 was the direct consequence of the U Nar Auk story.

Not all Kennedy's acquisitions were quite so aggressive. A Mr Dawson had operated a fleet of steamers out of Moulmein and on retirement in 1898 sold the business to the IFC and with it a railway called Dawson's Railway which he had built connecting Thaton with Duyinzeik the nearest port. In the 1920s, the company bought out the Indian-owned Burma Steam Launch Company that had been drawing away business for decades.

In the 1920s, the flotilla was at its zenith as Burma boomed and the majority of its abundant produce and busy people were carried on the flotilla's ships. With the Great Depression of the early thirties Burma went from boom to bust. The then manager, Thomas Cormack's task was to keep the ships running and the flotilla solvent which he successfully managed to do. That is why in this period not many new ships were ordered. This was a troubled time with peasant uprisings in the countryside and race riots in Rangoon, both the reaction of Burmese impoverished by unscrupulous Indian money lenders. Business picked up in the late 30s with the capture of Chinese sea ports by the Japanese and 'the Burma Road' becoming the main American military supply conduit to their ally Chiang Kai-shek trapped in the Chinese interior. Shipping to Bhamo became important again and on one occasion the company shipped an entire aircraft factory to Bhamo which was then carried over the hills only to be bombed to smithereens by the Japanese.

By the 1930s, an increasing number of Burmese joined the management of the company. The Burmese with their natural inclination towards learning were by this time producing a new generation of highly educated young men and some women who attended the new University of Rangoon. The trend would inevitably have been for the Burmese to have had an increasingly significant role in the running of the flotilla. A glance at the office staff photograph on Cormack's retirement in 1937 gives a good idea of the racial mix with as many smart young Burmese as Indians.

Office Staff on Cormacks Retirement 1937

Office Staff 1914

Likewise, on the ships by the twenties and thirties the Scots engineer was being replaced by the Anglo Burmese (many sons of Scots engineers who had married and stayed on). It was a similar story on the railways which became an Anglo Burmese fiefdom. After the war and nationalisation this westernised generation took over the running of the flotilla and there were few changes in working practices. When I worked with the IWT in the 1990s the entire system, right down to timetables and routings was identical to that of the old IFC. They changed nothing! I have an IFC handbook dated 1941 and an IWT handbook dated 1962 and they are more or less identical. That was perhaps the flotilla's most enduring legacy and it was the malaise and inertia of the Ne Win years that brought about the IWT fleet's decay. Alister McCrae and his wife who visited Rangoon on their way to New Zealand in 1954 were treated to a banquet by former Burmese colleagues and he was touchingly told that his nickname in the office had been 'Mandalay McCrae'.

Dorothy Laird in her book attributes the great success of the flotilla to the devotion of the ships commanders and crews in maintaining their ships to such a high standard. The other secret of success was financial probity and a very Scots concern with good bookkeeping drummed into every young assistant, whether training in the office of Paddy Henderson & Co or in the Cash Department of the Phayre Street office. You have six hundred ships each one with a cash box and ledger, you have fifty odd agents selling tickets and consigning cargos, and all this is controlled by a manager with a dozen assistants who spend much of their time buzzing around the Delta in speed boats to check everyone has a ticket. Alister McCrae tells the story of a six-hundred mile voyage up the Chindwin just to check on the agent at Homalin who it was rumoured was on the take.

When the investors of the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company attempted to set up an almost identical operation in Argentina in 1886 the project was destined to fail. The Rio Platanese Flotilla was plagued with losses and with lack of financial control money just flowed away. The same would have happened in Burma had it not been for the 'assistants'.

For the investors back home, the dividends paid out were not particularly high but IFC shares were regarded as a solid safe blue chip and the ships would sail on for ever. The company weathered the 1930s depression well and were progressively moving forward into new developments like ship building at Dalla and, well ahead of their time, aviation. The scuppering of the bulk of the fleet in 1942 to deny their use to the Japanese was a tragedy, but the company was by no means finished. They were due substantial war reparations and in 1947 ordered half a dozen M class ships from Denny's to replace the ones lost and in 1948, a similar number of P class vessels for the Bhamo run. They were all set to start up again in the newly independent Burma, but such dreams were put paid to by the nationalisation of 1948. So complex were its affairs that it took several years to wind up, with the disposal of so much property and when in 1957 it was finally struck off the register of companies in Scotland the investors all received something.

Further Reading

Dorothy Laird. The Story of Paddy Henderson and Company. London 1961.

Alister McCrae and Alan Prentice. Irrawaddy Flotilla. Paisley 1975.

Alister McCrae. Tales of Burma. Paisley 1981.

Alister McCrae. Scots in Burma: Golden Times in the Golden Land. Gartmore 1990.